- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This is an innovative collection of papers written by a panel of highly respected academics and financial experts. Whilst providing an insight into the phenomenology of the financial crises of the 1990s in Asia and Latin America, the book also explores possibilities for their solution.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Global Financial Crises and Reforms by B. N. Ghosh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Causes and correlates

1 The twin crises

The causes of banking and balance-of-payments problems

Graciela L. Kaminsky and Carmen M. Reinhart

Introduction

Pervasive currency turmoil, particularly in Latin America in the late 1970s and early 1980s, gave impetus to a flourishing literature on balance-of-payments crises. As stressed in Paul Krugman’s (1979) seminal paper, in this literature crises occur because a country finances its fiscal deficit by printing money to the extent that excessive credit growth leads to the eventual collapse of the fixed exchange rate regime. With calmer currency markets in the mid-and late 1980s, interest in this literature languished. The collapse of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, the Mexican peso crisis, and the wave of currency crises sweeping through Asia have, however, rekindled interest in the topic. Yet, the focus of this recent literature has shifted. While the earlier literature emphasized the inconsistency between fiscal and monetary policies and the exchange rate commitment, the new one stresses self-fulfilling expectations and herding behavior in international capital markets.1 In this view, as Guillermo A. Calvo (1995: 1) summarizes “If investors deem you unworthy, no funds will be forthcoming and, thus, unworthy you will be.”

Whatever the causes of currency crises, neither the old literature nor the new models of self-fulfilling crises have paid much attention to the interaction between banking and currency problems, despite the fact that many of the countries that have had currency crises have also had full-fledged domestic banking crises around the same time. Notable exceptions are: Carlos Diaz-Alejandro (1985); Andres Velasco (1987); Calvo (1995); Ilan Goldfajn and Rodrigo Valdés (1995); and Victoria Miller (1995). As to the empirical evidence on the potential links between what we dub the twin crises, the literature has been entirely silent. The Thai, Indonesian, and Korean crises are not the first examples of dual currency and banking woes, they are only the recent additions to a long list of casualties which includes Chile, Finland, Mexico, Norway, and Sweden.

In this paper, we aim to fill this void in the literature and examine currency and banking crises episodes for a number of industrial and developing countries. The former include: Denmark, Finland, Norway, Spain, and Sweden. The latter focus on: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Indonesia, Israel, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, the Philippines, Thailand, Turkey, Uruguay, and Venezuela. The period covered spans the 1970s through 1995. This sample gives us the opportunity to study 76 currency crises and 26 banking crises. Out-ofsample, we examine the twin crises in Asia of 1997.

Charles Kindelberger (1978: 14), in studying financial crises, observes: “For historians each event is unique. Economics, however, maintains that forces in society and nature behave in repetitive ways. History is particular; economics is general.” Like Kindelberger, we are interested in finding the underlying common patterns associated with financial crises. To study the nature of crises, we construct a chronology of events in the banking and external sectors. From this time-table, we draw inference about the possible causal patterns among banking and balance-of-payments problems and financial liberalization. We also examine the behavior of macroeconomic indicators that have been stressed in the theoretical literature around crisis periods, much along the lines of Barry Eichengreen et al. (1996a). Our aim is to gauge whether the two crises share a common macroeconomic background. This methodology also allows us to assess the fragility of economies around the time of the financial crises and sheds light on the extent to which the crises were predictable. Our main results can be summarized as follows.

First, with regard to the linkages among the crises, our analysis shows no apparent link between balance-of-payments and banking crises during the 1970s, when financial markets were highly regulated. In the 1980s, following the liberalization of financial markets across many parts of the world, banking and currency crises become closely entwined. Most often, the beginning of banking sector problems predate the balance-of-payment crisis; indeed, knowing that a banking crisis was underway helps predict a future currency crisis. The causal link, nevertheless, is not unidirectional. Our results show that the collapse of the currency deepens the banking crisis, activating a vicious spiral. We find that the peak of the banking crisis most often comes after the currency crash, suggesting that existing problems were aggravated or new ones created by the high interest rates required to defend the exchange rate peg or the foreign exchange exposure of banks.

Second, while banking crises often precede balance-of-payments crises, they are not necessarily the immediate cause of currency crises, even in the cases where a frail banking sector puts the nail in the coffin of what was already a defunct fixed exchange rate system. Our results point to common causes, and whether the currency or banking problems surface first is a matter of circumstance. Both crises are preceded by recessions or, at least, below normal economic growth, in part attributed to a worsening of the terms of trade, an overvalued exchange rate, and the rising cost of credit; exports are particularly hard hit. In both types of crises, a shock to financial institutions (possibly financial liberalization and/or increased access to international capital markets) fuels the boom phase of the cycle by providing access to financing. The financial vulnerability of the economy increases as the unbacked liabilities of the banking system climb to lofty levels.

Third, our results show that crises (external or domestic) are typically preceded by a multitude of weak and deteriorating economic fundamentals. While speculative attacks can and do occur as market sentiment shifts and, possibly, herding behavior takes over (crises tend to be bunched together), the incidence of crises where the economic fundamentals were sound are rare.

Fourth, when we compared the episodes in which currency and banking crises occurred jointly to those in which the currency or banking crisis occurred in isolation, we found that for the twin crises, economic fundamentals tended to be worse, the economies were considerably more frail, and the crises (both banking and currency) were far more severe.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The next section provides a chronology of the crises and their links. Section II reviews the stylized facts around the periods surrounding the crises while Section III addresses the issues of the vulnerability of economies around the time of the crisis and the issue of predictability. The final section discusses the findings and possibilities for future research.

I The links between banking and currency crises

This section briefly discusses what the theoretical literature offers as explanations of the possible links between the two crises. The theoretical models also guide our choice of the financial and economic indicators used in the analysis.

A. The links: theory

A variety of theoretical models have been put forth to explain the linkages between currency and banking crises. One chain of causation, stressed in James Stoker (1994), runs from balance-of-payments problems to banking crisis. An initial external shock, such as an increase in foreign interest rates, coupled with a commitment to a fixed parity will result in the loss of reserves. If not sterilized, this will lead to a credit crunch, increased bankruptcies, and financial crisis. Moreover, Frederic Mishkin (1996) argues that, if a devaluation occurs, the position of banks could be weakened further if a large share of their liabilities is denominated in a foreign currency. Models, such as Velasco (1987), point to the opposite causal direction—financial sector problems give rise to the currency collapse. Such models stress that when central banks finance the bail-out of troubled financial institutions by printing money, we return to the classical story of a currency crash prompted by excessive money creation.

A third family of models contend that currency and banking crises have common causes. An example of this may be found in the dynamics of an exchange rate-based inflation stabilization plan, such as that of Mexico in 1987. Theory and evidence suggest that such plans have well-defined dynamics.2 Because inflation converges to international levels only gradually, there is a marked cumulative real exchange rate appreciation. Also, at the early stages of the plan there is a boom in imports and economic activity, financed by borrowing abroad. As the current account deficit continues to widen, financial markets become convinced that the stabilization program is unsustainable, fueling an attack against the domestic currency. Since the boom is usually financed by a surge in bank credit, as banks borrow abroad, when the capital inflows become outflows and asset markets crash, the banking system caves in. Ronald I. McKinnon and Huw Pill (1996) model how financial liberalization together with microeconomic distortions—such as implicit deposit insurance—can make these boom–bust cycles even more pronounced by fueling the lending boom that leads to the eventual collapse of the banking system. Ilan Goldfajn and Rodrigo Valdés (1995) show how changes in international interest rates and capital inflows are amplified by the intermediating role of banks and how such swings may also produce an exaggerated business cycle that ends in bank runs and financial and currency crashes.

So, while theory does not provide an unambiguous answer as to what the causal links between currency and banking crises are, the models are clear as to what economic indicators should provide insights about the underlying causes of the twin crises. High on that list are international reserves, a measure of excess money balances, domestic and foreign interest rates, and other external shocks, such as the terms of trade. The inflation stabilization– financial liberalization models also stress the boom–bust patterns in imports, output, capital flows, bank credit, and asset prices. Some of these models also highlight overvaluation of the currency, leading to the underperformance of exports. The possibility of bank runs suggests bank deposits as an indicator of impending crises. Finally, as in Krugman (1979) currency crises can be the byproduct of government budget deficits.

B. The links: preliminary evidence

To examine these links empirically, we first need to identify the dates of currency and banking crises. In what follows, we begin by describing how our indices of financial crises are constructed.

Definitions, dates, and incidence of crises

Most often, balance-of-payments crises are resolved through a devaluation of the domestic currency or the flotation of the exchange rate. But central banks can and, on occasion, do resort to contractionary monetary policy and foreign exchange market intervention to fight the speculative attack. In these latter cases, currency market turbulence will be reflected in steep increases in domestic interest rates and massive losses of foreign exchange reserves. Hence, an index of currency crises should capture these different manifestations of speculative attacks. In the spirit of Eichengreen et al. (1996a and b), we constructed an index of currency market turbulence as a weighted average of exchange rate changes and reserve changes.3

With regard to banking crises, our analysis stresses events. The main reason for following this approach has to do with the lack of high frequency data that capture when a financial crisis is underway. If the beginning of a banking crisis is marked by bank runs and withdrawals, then changes in bank deposits could be used to date the crises. Often, the banking problems do not arise from the liability side, but from a protracted deterioration in asset quality, be it from a collapse in real estate prices or increased bankruptcies in the nonfinancial sector. In this case, changes in asset prices or a large increase in bankruptcies or nonperforming loans could be used to mark the onset of the crisis. For some of the earlier crises in emerging markets, however, stock market data is not available.4 Indicators of business failures and non-performing loans are also usually available only at low frequencies, if at all; the latter are also made less informative by banks’ desire to hide their problems for as long as possible.

Given these data limitations, we mark the beginning of a banking crisis by two types of events: (1) bank runs that lead to the closure, merging, or takeover by the public sector of one or more financial institutions (as in Venezuela 1993); and (2) if there are no runs, the closure, merging, takeover, or large-scale government assistance of an important financial institution (or group of institutions), that marks the start of a string of similar outcomes for other financial institutions (as in Thailand 1996–97). We rely on existing studies of banking crises and on the financial press; according to these studies the fragility of the banking sector was widespread during these periods. This approach to dating the beginning of the banking crises is not without drawbacks. It could date the crises too late, because the financial problems usually begin well before a bank is finally closed or merged; it could also date the crises too early, because the worst of crisis may come later. To address this issue we also date when the banking crisis hits its peak, defined as the period with the heaviest government intervention and/or bank closures.

Our sample consists of 20 countries for the period 1970 to mid-1995. The countries are those listed in the introduction and Appendix Tables A1 and A2. We selected countries on the multiple criteria of being small, open economies, with a fixed exchange rate, crawling peg, or band through portions of the sample; data availability also guided our choices. This period encompasses 26 banking crises and 76 currency crises.

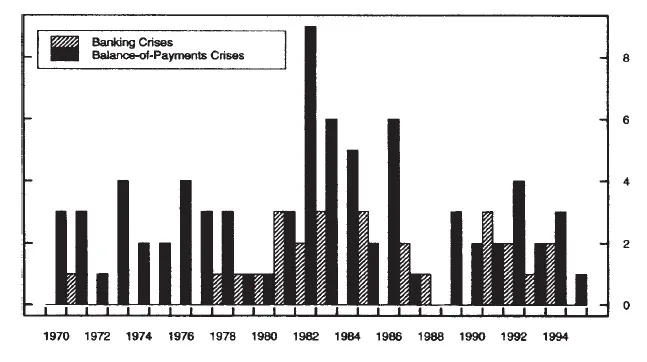

As to the incidence of the crises (Table 1.1 and Figure 1.1), there are distinct patterns across decades. During the 1970s we observe a total of 26 currency crises, yet banking crises were rare during that period, with only three taking place. The absence of banking crises may reflect the highly regulated nature of financial markets during the bulk of the 1970s. By contrast, while the number of currency crises per year does not increase much during the 1980s and 1990s (from an average of 2.60 per annum to 3.13 per annum, Table 1.1, first row), the number of banking crises per year more than quadruples in the post-liberalization period. Thus, as the second row of Table 1.1 highlights, the twin crisis phenomenon is one of the 1980s and 1990s.

Table 1.1 Frequency of crises over time

Figure 1.1 Number of crises per year.

Figure 1.1 also shows that financial crises were heavily bunched in the early 1980s, when real interest rates in the United States were at their highest level since the 1930s. This may suggest that external factors, such as interest rates in the United States, matter a great deal, as argued in Calvo et al. (1993). Indeed, Jeffrey Frankel and Andrew K. Rose (1996) find that foreign interest rates play a significant role in predicting currency crashes. A second explanation why crises are bunched is that contagion effects may be present, creating a domino effect among those countries that have anything...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Contributors

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part I Causes and correlates

- Part II Cases and caveats

- Part III Crisis management and reforms