eBook - ePub

Calculation and Coordination

Essays on Socialism and Transitional Political Economy

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This collection of essays from one of the major Austrian economists working in the world today brings together in one place some of his key writings on a variety of economic issues.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Calculation and Coordination by Peter J Boettke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

It has become somewhat of a modern cliché to insist that the collapse of Communism is one of the defining moments of twentieth-century political economy. Next to the Great Depression, the events of the late 1980s represent the political economy puzzle for us to solve. If the Great Depression shook a generation’s faith in the stability of the market economy, then the collapse of Communism smashed another generation’s hope that a socialist political and economic system offered a solution to capitalist ills that were at one and the same time more economically rational than the capitalist order and more consistent with the democratic values that progressive liberalism demanded. The reality of socialism prior to 1989 was long lines, lousy products, corrupt politics, a history of repression, and declining social system of provision in health and human services. The environmental degradation and increasing risk of major environmental disaster in the Soviet Union, for example, were evident even prior to Chernobyl. When Tatyana Zaslavskaya’s 1984 “Novosibirsk Report” was circulated among the ruling élite, nobody was really shocked by the content of her diagnosis of the existing system.1 Rather, it was the boldness with which she put forth the need for fundamental reform of that system that was shocking to the ruling élite. The Soviet system had so eroded the “surplus fund” that even a fortuitous oil shock could not have bailed out the system this time around, as it had in the 1970s. The system crumbled from within.2 The Soviet Union was but the most extreme form of this failed project in socialist political economy, and the rest of the Soviet Bloc followed suit. Ironically, the Soviet Union was actually the last to officially take the leap into the post-socialist era of political economy, but the reasons that this leap was necessary throughout the socialist world were strictly speaking Soviet ones.

Since 1989, the peoples of Eastern and Central Europe and, since 1992, the peoples of the former Soviet Union, have been attempting to accomplish a dual transformation in politics and economics. The euphoria of 1989 has given way to a sober reality, as this transformation has been neither easy nor obviously beneficial to the mass of citizens in terms of statistical measures of human well-being. According to official Russian statistics, 30% of the population (44 million people) was living below the poverty line (roughly $40/month) in September 1998. Life expectancy for adult males in Russia has declined from 64 in 1990 to 59 in 1998. It is estimated that 40% of Russia’s children are chronically ill. Since 1992 meat and dairy production is down 75%, grain production is down 55%, milk production down 60%, and Gross National Product is down 55%. Real per capita income is down as much as 80% from 1992 according to some measures. This was not without considerable attention from the West, who provided $90.5 billion in external assistance to Russia from 1991 to 1997. Socialist political economy was horrible enough, but how do we explain post-socialist political economy?3

Unfortunately, the mainstream of the economics profession was ill-equipped to both explain the failure of socialist political economy and provide a workable model of post-socialist political economy. It is perfectly understandable that, at such a momentous time, leaders both at home and abroad would turn to the “best and the brightest” that the discipline of economics had to offer.4 And the individuals called on were quite confident that they could redirect the post-socialist world in a more prosperous and peaceful direction. But the turbulent waters of post-Soviet reality have proved more difficult to navigate than was previously expected. Hindsight is, of course, 20/20, but some of these difficulties were predictable.

The biggest problem with the “transition according to Cambridge” (a phraseology introduced by Peter Murrell) was that the basic model of the Soviet period was mis-specified, and that the goal toward which the transition was to achieve has been underdefined.5 In a sense, on the path from “here to there,” the “here” wasn’t specified and the “there” was not defined. Without an accurate picture of “here to there,” there is no way to successfully navigate the path from socialism to capitalism.

Not everyone among the Harvard-Moscow cadre was guilty of this mis-specification, scholars such as Andrei Shleifer and Anders Åslund clearly understood more than others the “here” of the de facto reality of Soviet life.6 But the standard package of reforms discussed in the “Big Bang” versus “Gradualism” debate did not reflect an understanding of this de facto reality. This is not to say that the issue of policy simultaneity which underlies the “Big Bang” argument doesn’t hold. The “Big Bang” no doubt logically holds—tight monetary policy without fiscal restraint cannot be sustained, etc. But that doesn’t mean that “Big Bang” can ignore the evolutionary type of argument associated with “Gradualism.” Just as simultaneity is unassailable, so too is the argument that changes in the world largely occur in an incremental manner rather than in one shot.

There are three factors missing in this “Big Bang” versus “Gradualism” debate which cannot be overlooked if the real problems of post-socialist political economy are going to be engaged:

- the de facto property rights arrangement that existed under the old system;

- the institutional arrangements within which markets are to be embedded after reforms;

- the historical experience and cultural legacy of the country under examination, and specifically the question of the lived experience with market institutions as a carrier of legitimacy.

If we don’t pay attention to these issues, then we risk continual frustration due to mis-specification problems and the poor design of transition policies.

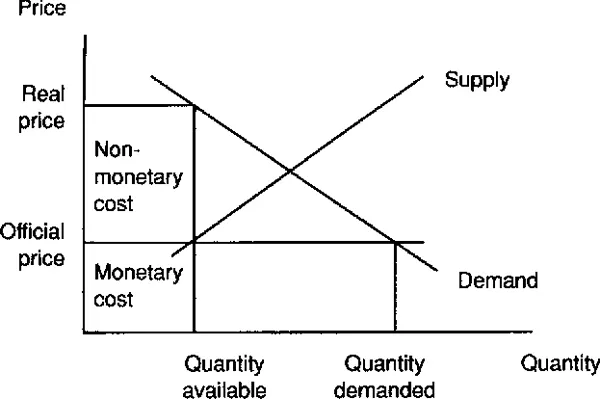

The work of public choice and market process scholars which animates my work has highlighted the incentive and informational difficulties associated with alternative institutional environments.7 However, we must also be willing to peer underneath given institutions and explore the legitimacy accorded to these institutions by different people. The basic institutions of a Western market society, for example, do not accord well with the lived experience of the Soviet peoples with markets. Formerly, the institutions of pricing and bargaining existed in both Soviet and post-Soviet periods. But during the Soviet period, the experience was one within the following situation: a black market without well-defined or enforced property rights, and a shortage of goods and lack of alternative supply networks. If we just look at the simplest depiction of this situation (see Figure 1.1), then perhaps we can begin to see the host of problems that arise under former Soviet conditions.

This very simple supply and demand configuration brings to the forefront the basic fact that in a shortage situation, the real price of obtaining the good in a shortage economy is higher than the official price. There is a gap between quantity demanded and the quantity supplied which creates a situation where there are non-monetary costs to buyers—associated with acquiring the good. Under “normal” market conditions, the costs to buyers are simultaneously benefits to sellers. But in the artificial shortage situation (caused by administered pricing), the non-monetary costs are not immediately benefits to the sellers, so the seller has a strong incentive to transform those non-monetary costs to buyers into benefits (monetary or non-monetary) for themselves. In other words, what this simple diagram reveals is the “rents” that are to be had by those who can exploit the shortage situation—rents that took the form of monetary “bribes,” “black-market profits,” and non-monetary “privileges” to those in special favor with the ruling élite. Markets were necessary for daily survival, but black (and other colored) markets are not the same as above-ground and legitimated markets backed by the rule of law, despite the formal similarity of prices and bargaining. The asymmetry between “markets” has to be the starting point of thinking about transition.8

Figure 1.1 Supply and demand in a shortage economy

Fixing this situation is not just a matter of freeing prices so they can adjust to the market clearing level. Of course, freeing prices is a necessary move, but it is not sufficient. “Getting the prices right” is not enough. What is required is the adoption of an intricate mix of institutions which enable individuals to realize the gains from exchange. But that intricate mix of institutions must be legitimated in the belief structures of the people. We cannot just impose whatever institutional structure we want wherever we want: the institutional structure has to be “grounded” in the everyday actions, beliefs, and ideas of the people.

The essays contained in this book, written over a decade of reflection on the founding, collapse, and transition from socialism in the former Soviet Union, were motivated by the idea that we cannot even begin to provide an answer to the political economy of the transition unless we start with an accurate description of Soviet reality. This explains the first word in the title of the book—Calculation. The argument, which originated in the work of Ludwig von Mises, concerning the impossibility of rational economic calculation under pure socialism, is the starting point of all my work in Soviet and post-Soviet political economy. Soviet socialism did not exist in pure form, that model was defeated by reality in the first years of the Soviet system’s existence, as explained in the essays on socialism. Instead, the mature Soviet system morphed into a political patronage system which is best modeled as a rent-seeking economy. The second word in the title—Coordination—refers to both the problem of the Soviet system in terms of magnitude of coordination failures which were evident in the political economy of everyday life under the Soviet system, and the solution to those problems in the sense that successful reform will lead to increased coordination of plans among economic actors, such that the most willing demanders and the most willing suppliers realize the mutual gains from free exchange. The title is also meant to convey the connection between these two key concepts -advanced complex coordination requires that economic actors are able to utilize the tools of economic calculation provided by private property, market prices and profit and loss accounting.

A theme that is reiterated again and again in the essays on transitional political economy and development in general is that institutions matter. It should be understood, however, that the reason for this emphasis on institutions is the role that entrepreneurship plays in lifting people beyond subsistence and how alternative institutional arrangements direct entrepreneurial activity in either productive or unproductive directions. Entrepreneurship—as described in the work of market process economists—is a necessary ingredient in the economic process in order that individuals can realize the mutual gains from exchange. Entrepreneurship takes at least two general forms:

- alertness to existing opportunities for mutual gain, and

- the discovery of new opportunities for mutual gain.

The prime mover of the economic system toward progress is entrepreneurial action. It is through the entrepreneurial process that we come to detect previous errors, adjust our behavior to correct those errors, and thus move to a state of affairs less erroneous than before. Entrepreneurial action is guided by relative price signals and the lure of pure profit (which requires the calculation of profit and loss accounting). Without these important indicators of economic life, the individual would be lost amid a sea of economic possibilities. However, these indicators are a product of specific institutional configurations and cannot be derived outside of that context. Absent the intricate institutional context of a private property market society, and individuals, while still striving to achieve their goals as best as they can, will be unguided by the incentives and informational surrogates which exist only within the private property monetary price system.

In lectures I have often invoked the image of a three-legged bar-stool to make the point about the necessity of this intricate institutional context for economic progress. The legs of the bar-stool represent:

- economics institutions,

- political/legal institutions, and

- social/cultural institutions.

Unless all three legs are equally strong, the bar-stool will not be able to stand when we sit on it. Russia’s problems are not limited to the underdevelopment of economic institutions, but are just as much (and probably more) due to the underdevelopment (and mal-development) of political/legal and social/cultural institutions.

The essays in this volume lean toward the conclusion that while there are many different ways that people choose to live throughout our world, there are very few ways for them to live peacefully and prosperously as a society. The book begins with an essay that argues that this conclusion has as much to do with the analytical contributions of economics as it does with normative judgments. The book ends with some concluding remarks on the relationship between economic freedom, economic growth, and general measures of human well-being. I do not believe that aggregate measures of economic growth capture all there is to understand about the human condition—in fact, along with other market process economists, I am quite skeptical of aggregate economics in general and statistical analysis in particular (see Boettke 1993, pp. 21–5). But getting our best guesses on the table can be a valuable exercise, and identifying the possible proxies for human well-being does, on the margin, aid the conversation we are engaged in concerning the human condition within developing economies.

I also do not fear normative theorizing in political economy; in fact, I welcome it (see Boettke 1993, p. 146). But in my work I have tried to insist that political economy is a value-relevant discipline, precisely because economics can provide knowledge that, to the best that we are humanly capable, can be termed value-neutral. In other words, I have tried to carve out a niche where the assessment of socialism and capitalism does not solely turn on whether the analyst has individualist or collectivist values. The consequentialist arguments for private property, freedom of contract, open trade, free pricing, monetary stability, and fiscal restraint are not strictly speaking “value-free.” To advocate a policy position requires the importation of values. But the consequentialist critiques of collective property or even attenuated private property rights; the abolition of commodity production or even restricted market activity; administered pricing; soft-budget constraints; and monetary instability are, in principle, “value-neutral.” The logic of these arguments can be, in principle, accepted by both the advocate and the critic of the proposed policy.

The essays in this volume are not meant to close the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foundations of the Market Economy

- Illustrations

- Copyright acknowledgments

- Acknowledgments

- 1: Introduction

- 2: Why are there no Austrian Socialists? Ideology, science, and the Austrian school*

- 3: Economic calculation The Austrian contribution to political economy*

- 4: Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom revisited Government failure in the argument against Socialism*

- 5: Coase, Communism, and the “Black Box” of Soviet-type economies*

- 6: The Soviet experiment with Pure Communism*

- 7: The political economy of utopia Communism in Soviet Russia,1918–21*

- 8: Soviet venality A rent-seeking model of the Communist state*

- 9: Credibility, commitment, and Soviet economic reform*

- 10: Perestroika and public choice The economics of autocratic succession in a rent-seeking society*

- 11: The reform trap in economics and politics in the former Communist economies*

- 12: Promises made and promises broken in the Russian transition*

- 13: The Russian crisis Perils and prospects for post-Soviet transition*

- 14: The political infrastructure of economic development*

- 15: Why culture matters Economics, politics, and the imprint of history*

- 16: Concluding remarks

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- Notes