1 The European Union and the public sphere

A communicative space in the making?

John Erik Fossum and Philip Schlesinger

The public sphere is a central feature of modern society. So much so that, even where it is in fact suppressed or manipulated, it has to be faked.

(Taylor 1995: 260)

Introduction

After two decades of almost breathtaking integration, the French non (by 54.7 per cent) and the Dutch nee (by 61.6 per cent) to the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe in May and June 2005 underlined that the Union had arrived at a critical juncture. Whatever sense of direction could be derived from a decades-long process of integration has apparently given way to profound uncertainty and heightened contestation over the Union’s future development. This has precipitated a ‘reflection period’, as well as initiatives by the Commission to improve its communication policy (cf. European Commission 2006).

The referendum results have been received and interpreted very differently across Europe. Euro-sceptics have construed the outcome as clear evidence that a European constitutional polity is a dream, a fiction that can never be realised in practice. Euro-federalists, on the other hand, have seen the rejection as testimony to the inadequacy of the Constitutional Treaty (CT) as an instrument for establishing a federal EU polity. This gap in interpretations dramatises current debate over what is, and might be, the character of the EU.

The outcome is directly connected with the concerns of our book, namely, what the prospects are for a European public sphere.

Arguably, a central precondition for a democratic order is a viable public sphere – namely, a communicative space (or spaces) in which relatively unconstrained debate, analysis and criticism of the political order can take place. This precondition applies as much to the EU as it does to any nation state.

In the Union’s early stages, the task was to consolidate democracy at the national level and to overcome the legacy of the Second World War. The EU (like its precursors) has acted as an important consolidator of democracy in post-authoritarian and post-communist states that have acceded to the Union. As the Union has grown, the concern with democracy has been a question posed not only about member states and newly acceding states but also about the workings of the EU itself. There is now a strong onus on the Union to comply with democratic norms. It has become increasingly – and pressingly – relevant to discuss whether there could be a European public sphere in which citizens might simultaneously address common issues across state borders and see themselves as the authors of the EU laws they have to abide by. The EU’s development as a new kind of polity is therefore closely connected with the range and depth of its development as a public and communicative space. Inasmuch as the Union actually might serve as an exemplar for the development of postnational democracy at the supranational level, surely such a process has to be rooted in the reshaping of the EU as an overarching communicative space (or spaces) that might function as a public sphere.

Traditionally, both political and media theory have conceived of communicative spaces and public spheres in terms of what goes on inside nation states.1 However, this kind of perspective is rapidly ceasing to be adequate to account for how the EU works as a supranational polity. The integration process has provoked nationalist opposition inside member states as well as reassertions of regionalism and nationalism at the sub-state level. More distinctive spaces below the level of the member state are being reinforced at the same time as the nation-state framework itself is facing new challenges from above.

In addressing the changing political configuration of the EU, this book begins by asking:

- What are the prospects for a European public sphere?

- Is a uniform sphere needed, or are overlapping public spheres a more viable option?

- What do our findings tell us about the EU as a polity?

When considering these questions, first we have to clarify what a ‘public sphere’ means, and what its functions are. We have to take into consideration that a public sphere is imbricated in a set of legal–institutional arrangements traditionally linked to the nation state. Consequently, it has been quite common to imagine the public sphere in rather monolithic terms.

However, the EU is neither a state nor a nation and, as we shall argue, it remains unclear whether any public sphere at the Union level could be modelled on that presently associated with the nation state. The challenge to democratic theory, therefore, is what kind of conception of the public sphere might be relevant to the EU.

In this chapter, first we take, as our point of departure, the Haber- masian model of the public sphere and make explicit its presuppositions. Habermas’s thinking has been influential in the debate on the contemporary public sphere, and he has also repeatedly sought to apply his theory to the EU. This makes his contribution a natural starting point for any book on the European public sphere. Second, we consider some problems in the workings of the public sphere. Third, we develop two distinct conceptions of an EU still in the making. These differ greatly in their implications for the prospects of a European public sphere.

Conceptualising the public sphere2

In conceptualising the public sphere, it is important to deal with three core issues. First, we need to establish its ideal characteristics, so as to bring out the relevant analytical dimensions. Second, we have to spell out its contribution to democracy and its normative value. Third, we identify some key problems that the public sphere is currently facing. Publicsphere theorising has taken the nation state as its point of reference and normative template. However, our investigation of the European public sphere seeks to avoid simply juxtaposing the emergent European reality to a ‘model’ public sphere based on the template of the nation state.

In Habermas’s characterisation, the public sphere:

can best be described as a network of communicating information and points of view […]; the streams of communication are, in the process, filtered and synthesized in such a way that they coalesce into bundles of topically specified public opinions. Like the lifeworld as a whole, so, too, the public sphere is reproduced through communicative action, for which mastery of a natural language suffices; it is tailored to the general comprehensibility of everyday communicative practice.

(Habermas 1996a: 360)

The public sphere has a triadic character, with a speaker, an addressee and a listener. In an ideal ‘public sphere’, equal citizens assemble into a public and set their own agenda through open communication. In Habermas’s developmental account, the new spaces of ‘public reasoning’ that opened up for the political confrontation between state authorities and the public were held to be remarkable and without historical precedent (Habermas 1989: 27). Habermas has conceived the public sphere as non-coercive, secular and rational. A central feature is its reflexive character: it is how a ‘society’ talks knowingly about itself.

Individual rights that provide citizens with protection from incursions by the state serve as a vital precondition for the public sphere. Habermas’s initial account in the Structural Transformation (1989) was based on a reconstruction of the ideal features of the bourgeois public sphere. This, he argued, underwent a subsequent decline in the age of organised capitalism and corporate democracy, which he described as ‘a neocorporatist “societalization of the state” […], and as a state-ification of society’ (Habermas 1992a: 432). In his more recent work, Habermas has linked the notion of a public sphere more closely to the principle of universalistic argumentation, the principle that forms the core of the theory of communicative action. Craig Calhoun explains this transition in the following way:

where Structural Transformation located the basis for the application of practical reason to politics in the historically specific institutions of the public sphere, the theory of communicative action locates them in transhistorical, evolving communicative capacities or capacities of reason conceived intersubjectively as in its essence a matter of communication.

(Calhoun 1992: 32)

This alters the theoretical status of the public sphere: ‘The public sphere remains an ideal, but it becomes a contingent product of the evolution of communicative action, rather than its basis’ (ibid., emphasis added).

Whereas Habermas’s definition cited above locates the public sphere in the ‘lifeworld’, this is not the whole picture, as he also seeks to establish the prospects for communicative action within the political system in general. After being criticised by, among others, Nancy Fraser (1992), Habermas has himself acknowledged that formally organised institutions within the system world also contain fora that may play the role of publics. Fraser initially captured this added complexity in a key distinction between ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ publics. Strong publics are spaces of institutionalised deliberation ‘whose discourse encompasses both opinion formation and decision making’, and weak publics are spaces ‘whose deliberative practice consists exclusively in opinion formation and does not also encompass decision making’ (ibid.: 134).

In institutional terms, strong publics encompass parliamentary assemblies and other deliberative entities: they are situated in formally organised institutions imbued with decision-making power and – ideally – should be constrained by the logic of argument and impartial justification. Weak publics operate in the wider sphere of deliberation outside the formal political system; in short, in civil society. From this standpoint, it is the interrelations between strong and weak publics that make up the wider constitutional order associated with the democratic constitutional state.

The public sphere and democracy

The public sphere is intimately linked with democracy. Since it is based on the tenet that everybody can speak without limitation, it can be considered a precondition for realising popular sovereignty. Legal rights – in particular, those of freedom of expression and of assembly – secure the public sphere as a common space for communication. It is the communicative context in which problems are discovered, thematised and dramatised. Here, they are also formed into opinions and wills on the basis of which formal decision-making agencies are empowered to act.

According to Charles Taylor:

[T]he public sphere is not only a ubiquitous feature of any modern society; it also plays a crucial role in its self-justification as a free selfgoverning society, that is as a society in which (a) people form their opinions freely; both as individuals and as coming to a common mind, and (b) these common minds matter – they in some way take effect on or control government.

(Taylor 1995: 260)

Plainly, the development of a modern public sphere has profound implications for how democratic legitimacy may be conceived. When citizens become equipped with rights they can exercise against the state, decision makers also face the need to justify their decisions and to gain support in public. In such a setting, power cannot be legitimated solely by reference to divine law or traditional authority. Instead, authority is to be discovered in the public’s ‘reasonable’ discussion. This makes legitimacy precarious but it also becomes an important democratic resource. The speech of power can be turned into the power of speech (Lefort 1988: 38). Within this framework, it is clear that particular institutions or concrete persons cannot guarantee the legitimacy of the law. Only public debate in itself has norm-giving power (Eriksen and Weigård 2003).

A functioning public sphere presupposes basic rights that ensure the autonomy of citizens, both in private and in public terms, and institutions that can relay communicative action originating in the lifeworld to the system world. Such institutions include ‘strong’ publics with a deliberative vocation as well as executive and legislative institutions that ensure that decisions are made and carried out. Habermas notes that:

binding decisions, to be legitimate, must be steered by communication flows that start at the periphery and pass through the sluices of democratic and constitutional procedures situated at the entrance to the parliamentary complex or the courts […]. That is the only way to exclude the possibility that the power of the administrative complex, on the one side, or the social power of intermediate structures affecting the core area, on the other side, become independent vis-à-vis a communicative power that develops in the parliamentary complex.

(Habermas 1996a: 356)

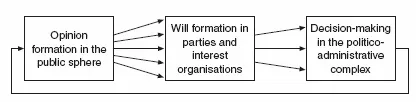

This can be represented in a model of what Habermas terms the ‘official circulation of power’, i.e. that which is actually set down in the formal constitution of the democratic constitutional state. This is a heuristic device that enables a clearer delineation of both the constitutive elements of the public sphere and its presuppositions. It can be illustrated as in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The circulation of political power.

The model presupposes that opinion formation takes place outside the political system, is inserted into the system through ‘channels and sluices’ and emerges as decisions. How such decisions are justified helps to frame subsequent processes of opinion-formation through a feedback loop.

The application of this model to contemporary reality raises three critical issues of direct relevance for our conception of a public sphere. The first pertains to the types of presupposition that need to underpin a viable public sphere. Do democratic opinion- and will-formation processes have to rest on a set of ‘pre-political’ values to produce democratically legitimate decisions? Does democracy presuppose a we-feeling, a sense of brotherhood and sisterhood akin to that associated with what Benedict Anderson (1991) has famously called the ‘imagined community’ of the nation? Is a sense of common destiny required for people to consider each other as compatriots willing to trust each other and take on collective obligations?

Communitarianism provides us with the clearest response to such questions and holds that identity is value-based and that notions of the good have priority over notions of justice (Sandel 1998). Without binding norms or shared values, it is argued, societal co-operation cannot come about, and without this it is not possible to explain order as the result of co-operation between free and equal citizens. People need to regard each other as norm-abiding actors in order for solidarity and collective action to occur on a voluntary basis. What is more, communitarians hold that political integration does require a deeper sense of belonging and commonality (Miller 1995). In Amitai Etzioni’s (1997) terms, members of a community listen to the same moral voice. The citizens need to regard each other as neighbours or fellow countrymen, or brothers and sisters.

It is this kind of common identification, arguably, that makes for solidarity and patriotism. This type of political integration is held to be the achievement of the nation which, ideally, due to its deep ties of belonging and trust, makes possible the transformation of an aggregation of individuals and groups into a collectivity capable of common action. Communitarianism’s position on the character of the circuit of political power is thus clear: an absence of shared norms coupled with increased social scale and heterogeneity will make consensual decisions highly unlikely, causing systemic instability or even breakdown.

The presumption of an intrinsic link between national identity and democracy has deeply coloured the academic and political debate on the EU. Many students of European integration have maintained that a democratic Union must emulate the nation state to promote social and political integration and develop ‘pre-political’ elements such as a collective identity, common values and common interests (see, for example, Grimm 1995; Miller 1995; Offe 1998). The communitarian perspective requires a high threshold for what constitutes a viable European public sphere – one that the highly diverse Union will find very hard to step across.

By contrast, liberals and deliberative democrats argue that the communitarian position is based on an historical fiction: communitarians are held to underrate democratic systems’ ability to accommodate an evolving pluralism and diversity. Furthermore, by stressing the need for a prepolitical identity, communitarians may actually overstate the cohesion that modern states require. As Klaus Eder notes in Chapter 3 (pp. 55–56, our emphasis), ‘Nationalism distorts the idea of equal citizens into the idea of a unitary people. […] This need for an ontological unity is the central risk of the national variant of a democratic state.’

National public spheres are neither as unitary as communitarians posit nor should we assume that they are paragons of openness and democratic participation. For instance, we may well find that, at the national level, the mediated public sphere operates far from perfectly. In the UK, for instance, there is debate about political communication that emphasises the failure of politicians to communicate effectively or honestly, their recourse to image and news management, the marginalisation of Parliament and the centralisation of executive power. For some critics, media coverage has contributed to a loss of respect for the political class, t...