1 Introduction

International policing is often invoked as the inevitable answer to global threats such as terrorism and drug trafficking. To the extent that terrorists and drug traffickers operate beyond national borders, states need to cooperate internationally to suppress the phenomenon. From a problem-solving perspective, states can hardly be justified in refusing to cooperate at an international level against terrorism and drugs. In fact, if we accept that global threats must be fought collectively for the struggle to succeed, then the failure of a state to cooperate can only be attributed to a fatal lack of awareness, if not outright complicity with the criminals.

From a different perspective, international police cooperation poses a real challenge to states.1 The reason is that it impinges on the territorial monopoly of the legitimate use of force, which in the tradition of Max Weber is considered to be the defining characteristic of modern statehood. If this is true, then states should be expected to watch jealously over their monopoly of force. Insofar as policing is the epitome of this monopoly, states should be unlikely to accept any binding commitment to international police cooperation. Accordingly, there should be close limits to the willingness of states to engage in international policing.

On the one hand, states are motivated by an interest in fighting global threats such as international terrorism and drug trafficking; on the other hand, they are constrained by an interest in maintaining national sovereignty and the monopoly of force. Apart from this dilemma, states are also torn by other countervailing incentives. While there is a wide array of institutions to facilitate international police cooperation, existing institutions such as Europol can also make it more difficult for states to promote international policing in more encompassing frameworks, such as Interpol. Even normative ideas can either motivate a state to cooperate, as for example when there is moral outrage after a terrorist attack; or they can act as obstacles, as for example when a state prefers a permissive attitude to the idea of ‘zero tolerance’ for drugs.

International policing is of clear empirical, theoretical, and normative relevance. The empirical relevance is obvious, especially with regard to the fight against global threats such as terrorism and drugs. Nevertheless, ‘want’ and ‘can’ do not automatically derive from ‘ought’. International policing is anunlikely area for harmonious cooperation due to its direct relationship with sovereignty and the monopoly of force. The conditions under which international police cooperation can take place are therefore also of theoretical relevance. Furthermore there are also normative reasons for concern, given that the monopoly of force has served as the foundation of national and international order for centuries. It is problematic, to say the least, if states allow that monopoly to be eroded with no clear alternative.

In short, the analytical objective of this book is to shed light on ‘who wants what, when, why’ with regard to international policing. How far, under which circumstances, and for what reasons are states willing, or unwilling, to internationalize their monopoly of force?

The focus is on the preferences of four large Western European states: the United Kingdom, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, and Italy. These countries are interesting because they tend to prefer an international crime-fighting approach to the more militaristic approach of the United States (Katzenstein 2003; Andreas and Nadelmann 2006). While there is still no European Leviathan in the making, the internationalization of the monopoly of force is uniquely advanced in Europe. Nevertheless, European countries sometimes share the ‘instinct’ of other modern states to preserve their monopoly of force as much as possible.

One thing needs to be established right from the start. Britain, France, Germany, and Italy have been selected because they constitute an interesting sample of comparable countries, and not simply because they are Member States of the European Union. They seek cooperation in any geographical and institutional framework, from the United Nations to bilateral forms of cooperation, and from the OECD to the Council of Europe. The EU is only one of these geographical and institutional frameworks, although it is true that in recent times it has attained a privileged status. The four countries selected are not treated as EU Members, but as members of the international system. Despite the selection of European countries, this book is not an exercise in EU studies, but rather a contribution to international relations in general.

In the remainder of this chapter, let me introduce state preferences and international police cooperation as the core concepts of the study and provide some preliminary methodological considerations. The first section derives a conceptual understanding of state preferences from the theoretical literature. The next two sections place the notion of international policing in the wider perspective of historical political sociology. The second section expounds Max Weber’s understanding of the monopoly of force and introduces the idea of a ‘chain of coercion.’ The third section provides a historical sketch of the evolution of the monopoly of force and characterizes international policing as potentially leading to a transformation of modern statehood. The fourth section, finally, contains reflections on abduction as a pragmatic research strategy and prepares for the concrete application of this methodology in Chapter 2, and throughout the book.

State preferences

According to the title of a famous book, politics is about Who Gets What, When, How (Lasswell 1936). As this oft-quoted slogan suggests, the essence of politics is strategic interaction in order to obtain distributive outcomes. After seventy years, the view of politics as ‘who gets what, when, how’ still appeals to many political scientists. According to this view, the analytical focus of political science must be on bargaining and implementation, while the political preferences of the actors involved can be taken as given.

Against this, one might reasonably argue that an answer to the question of ‘who gets what, when, how’, even where it is possible, hardly leaves us satisfied. Logically, it begs the prior question of ‘who wants what, when, why’. If we stop taking preferences as given, we immediately realize how much difference it makes whether the actors involved in a political issue want one thing rather than another. In fact, the analysis of strategic interaction and its distributive outcomes hardly makes any sense without a previous understanding of the preferences of the actors involved.

For example, it is certainly an interesting question to ask who carries the day in the fight against terrorism and drugs: European states with their predilection for a crime-fighting approach, or the United States with their penchant for a ‘war on drugs’ and a ‘war on terror’. Arguably, however, the question of why European states differ from the US in their approach to terrorism and drugs is as interesting as the question of who succeeds in shaping the concrete terms of international cooperation and their practical outcomes.

Both in the general case of international politics and in the particular case of international policing, it is important to understand what states want, why, and under what circumstances they want it, and what this entails for international cooperation. Only if we learn to understand national preference formation, can we ever hope to properly understand international politics and its distributive outcomes. This is not to say that outcomes can be directly deduced from preferences. International politics follows the logic of collective action, which almost necessarily implies paradoxical effects and unintended consequences. Nevertheless, national preferences are logically and chronologically prior to social interactions, and they are therefore a precondition for the understanding of the international political process.

In general, preferences can be understood as either exogenous or endogenous to social interaction. For an exogenous understanding, take as an example the following definition: ‘When we speak of a person having a preference, we mean that the person can connect choices by a relationship that indicates that the person likes one alternative better than, or just as much as, another’ (Bueno de Mesquita 2001: 241). It is understood that all alternatives are fully available, and the person can choose freely among them. Accordingly the preferences are understood as independent from, or exogenous to, social interaction.

Social constructivists prefer an endogenous understanding of preferences. From this perspective preferences are a function of social intercourse, and they must be expected to change as intercourse unfolds (Gerber and Jackson 1993). Actors are seen as defining and redefining their preferences in a social environment, presumably following the ‘logic of appropriateness’ rather than the ‘logic of consequences’.2 Together with the fluctuations of social intercourse, preferences are expected to fluctuate (Adler 1997; Checkel 1998).3 They are therefore understood as being dependent upon, or endogenous to, social interaction.

In this book, I adopt a third possibility between these extremes: positional preferences. Let us assume that the preferences of an actor are determined by ‘the way it orders the possible outcomes of an interaction’ (Frieden 1999: 42).4 This implies a ranking among the anticipated results of social or political intercourse (see Clark 1998).5 The possible outcomes are not commodities among which the actor can choose freely, since they depend on the strategic behaviour of other players. Thus understood, preferences are not exogenous because they always imply social interaction. However, preferences are not entirely endogenous either because they are a function of anticipated (and not ongoing) interaction.

The exogenous understanding of preferences may be adequate for situations in experimental psychology or microeconomic modelling; the endogenous understanding may be adequate for constellations of identity politics and groupthink; however, it is positional preferences that are most adequate in political science. In a political situation, the preferences of an actor are almost always dependent on the choices that are effectively available in a strategic context. Actors anticipate the preferences, power, and strategic behaviour of their fellow actors, and this in turn influences them in the way they formulate their own preferences.

If we apply this to international politics, state preferences can be defined as ‘an ordered and weighted set of values placed on future substantive outcomes, often termed “states of the world”, that might result from international political interaction’ (Moravcsik 1998: 24). Since state preferences are related to the anticipated outcomes of political interaction, they can be conceptualized by an analytical two-step. In the first step, states formulate their preferences; in the second step, they bargain over substantive outcomes (Legro 1996: 119).6

When talking about state preferences (or national preferences), I usually mean the preferences of the state as a corporate or collective actor. Of course the state is not monolithic, and it is an abstraction to attribute preferences to it as if it were an individual person. Nevertheless governments often do have the ability, just as people, to connect choices by a relationship that indicates that they like one potential outcome of social interaction better than another (Scharpf 1997: 54–8). At least for large and important states it is reasonable to assume that, more often than not, their ideas about foreign policy objectives are sufficiently clear to justify talking about state preferences.

Empirically, state preferences can be understood as government preferences to the extent that a government represents a country in a meaningful way. In international relations this condition is usually met, for example when governments send executive representatives to the negotiation table and closely supervise their bargaining moves.7 This is particularly true in policy fields that are closely controlled by the executive branch of the state, such as military cooperation or international police cooperation.

The monopoly of force

There is a wide consensus that the monopoly of the legitimate use of force – henceforth ‘the monopoly of force’ – is the defining characteristic of modern statehood (Grimm 2003: 1044–5).8 As one scholar has put it, ‘the state’s function is policing. States have a common interest in monopolizing coercion within their territories’ (Thomson 1995: 226–7).

The German sociologist Max Weber, in his famous lecture Politics as a Profession, defines the state as a human association that successfully claims the monopoly of legitimate physical violence in a given territory. The modern territorial state, which is understood by Weber as only one among many possible devices for people to rule over people, claims to be the only legitimate source of the right to use force (Weber 1992 [1919]: 5–13).

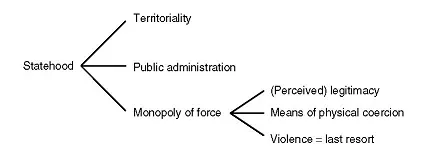

In his posthumous oeuvre, Economy and Society and Staatssoziologie, Weber left additional clarifications to his understanding of the modern state (Weber 1968 [1922]: Ch.1 §17, Ch.9 §1–2; 1956: §3). Overall, he distinguished three defining characteristics of modern statehood. The first two are territoriality and public administration. The third and decisive one is the monopoly of force. Weber remarks that it is usually sufficient for a state to use physical violence as a last resort – that is, only when other means of disciplining have failed. Insofar as such latent force is generally perceived as legitimate, it is the monopoly of the physical use of force that makes the modern state so extremely powerful.

This is not to deny that people rule over people by means of many institutions other than the state. It is easy to see, however, that the modern state is distinct from any of these. A Mafia organization uses force in a given territory, but it is neither accepted as legitimate nor managed through public administration. Trade unions are territorially organized and managed through administration, but they are not entitled by law to use force. In traditional societies the housefather is sometimes authorized to use coercion, but he has no territory and does not manage his family through administration. Moreover, his right to use coercion is mostly residual insofar as it is located in a sphere that has been deliberately left unregulated by the law. The same can be said about the right of the citizens of some states to hold guns (Malcolm 2002).9

Figure 1.1 The monopoly of force according to Weber.

According to a Weberian (or ideal-typical) understanding of the monopoly of force, in the modern world only the state can exercise or delegate the legitimate ‘right’ to use force. This begs the question: what does it take for such an ideal-typical modern state to effectively control the monopoly of force? Let us recall that, according to Max Weber, the monopoly of force is the monopoly of the legitimate use of the physical means of coercion. To fully control the monopoly of force, it is not sufficient for a modern state to monopolize the physical means of coercion alone. A modern state and/or its citizens would also need to be in a position to define autonomously when the physical use of these resources is legitimate.

While this is certainly true, it begs another question. Even if there is a consensus that the use of force is legitimate in a particular case, it does not necessarily follow that any means to tackle the case is allowed. At least in the case of modern bureaucratic and constitutional states, there is no direct link from the legitimacy of force to its physical use. A modern state would also need to control the choice of the methods by which coercion shall be applied.

All this amounts to a ‘chain of coercion’ that reaches from the legitimization of force to the choice of appropriate methods, and from the choice of appropriate methods down to the physical use of force. Both in the field of military coercion and in the field of policing (see Figures 1.2 and 1.3), it is possible to draw such an ideal-typical chain with the actual use of force as the last resort.

In an abstract, ideal-typical world, the state is in a position to define, on normative grounds, the internal and external threats against which force shall be applied (discourse level). Furthermore, the state ha...