Institutional Change in the Payments System and Monetary Policy

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Institutional Change in the Payments System and Monetary Policy

About this book

"Central bankers worldwide welcome the recent increase of research on payment systems. This volume, providing an expert overview on this timely subject, should be required reading for us all". - Erkki Liikanen, Governor of the Bank of Finland

Monetary policy has been at the centre of economic research from the early stages of economic thought, but payment system research has attracted increased academic attention only in the past decade. This book's succeeds in merging these two so far largely separated fields.

Innovative and groundbreaking, Schmitz and Woods initiate research on the interdependence of institutional change in the payments system and monetary policy, examining the different channels via which payment systems affect monetary policy. It explores important themes such as:

- conceptualization and methods of analysis of institutional change in the payments system

- determinants of institutional change in the payments system – political-economy versus technology

- empirics of institutional change in the retail and in the wholesale payments systems – policy initiatives and new technologies in the payments system

- implications of institutional change in the payments system for monetary policy and the instruments available to central banks to cope with it.

The result is an accessible overview of conceptual and methodological approaches to institutional change in payment systems, and a comprehensive and yet thorough assessment of its implications for monetary policy. The insights this timely book provides will be invaluable for researchers and practitioners in the field of monetary economics.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Information

1

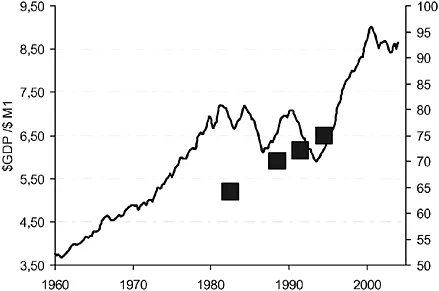

Payments system innovations in the United States since 1945 and their implications for monetary policy

The revolutions that haven’t yet happened

Credit and debit cards

Table of contents

- Routledge International Studies in Money and Banking

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Notes on contributors

- Institutional change in the payments system and monetary policy – an introduction

- 1 Payments system innovations in the United States since 1945 and their implications for monetary policy

- 2 Payment systems from the monetary policy implementation perspective*

- 3 Modelling institutional change in the payments system, and its implications for monetary policy

- 4 The evolving payments landscape and its implications for monetary policy

- 5 eMoney and monetary policy: the role of the inter-eMoney-institution market for settlement media and the unit of account

- 6 What drives demand for and supply of electronic money? Theoretical background and lessons from history

- 7 Monetary policy in a world without central bank money

- 8 The organisation of interbank settlement systems: current trends and implications for central banking

- Index