- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

How Economists Model the World into Numbers

About this book

Economics is dominated by model building, therefore a comprehension of how such models work is vital to understanding the discipline. This book provides a critical analysis of the economist's favourite tool, and as such will be an enlightening read for some, and an intriguing one for others.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction

Only a further development of the engineering skill of econometrics will help in this respect.(Tinbergen [1936] 1959: 84)

But technique is interesting to technicians (which is what we are, if we are to be of any use to anyone)(Lucas 1987a: 35)

A separate methodology of models

The practice of economic science is dominated by model building. Therefore, to understand economic practice we must try to apprehend how models function in economic research. The kinds of models discussed in this monograph are the mathematical models built and applied in empirical economic research, particularly in macroeconomics and econometrics. These models are meant as quantitative representations of our world. Their function is to generate numbers to inform us about economic aspects of the world. The central problem of this monograph is the assessment of the reliability of these bodies of knowledge.

In modern economics, it is taken for granted that quantitative expressions of our world are useful and that mathematical representations constitute–even better –knowledge about economic phenomena. This latter belief was explicitly voiced by Irving Fisher (1867–1947), one of the founders of modern economics:

The effort of the economist is to see, to picture the interplay of economic elements. The more clearly cut these elements appear in his vision, the better; the more elements he can grasp and hold in mind at once, the better. The economic world is a misty region. The first explorers used unaided vision. Mathematics is the lantern by which what before was dimly visible now looms up in firm, bold outlines. The old phantasmagoria disappear. We see better. We see also further.(Fisher [1892] 1925: 119)

This statement was made in the very last section of Fisher’s PhD thesis Mathematical Investigations in the Theory of Value and Prices, written in the last decade of the nineteenth century. When Fisher wrote his PhD, the belief that economic phenomena could be better understood through mathematics was not widely held. His work marked the beginning of a new era in which, bit by bit, economics became mathematicised. This process of mathematisation took not place by means of translating verbally expressed theories, one by one, into mathematical language, but through the emergence of a new practice of economic research characterised by mathematical modelling.1 To understand their specific function in economic research, models should be distinguished from economic theories. As will be shown, they are not theories about the world but instruments through which we can see the world and so gain some understanding of it. As mathematical representations, models should also be distinguished from pure formal objects. They should be seen, as the quote above says, as ‘lanterns’, as devices that help us to see the phenomena more clearly. Models are the economist’s instruments of investigation, just as the microscope and the telescope are tools of the biologist and the astronomer. In a textbook on optical instruments, we find the following description that can easily be projected on models:

The primary function of a lens or lens system will usually be that of making a pictorial representation or record of some object or other, and this record will usually be much more suitable for the purpose for which it is required than the original object.(Bracey 1960: 15)

In the same way, models can be used to function as instruments to perform a particular kind of observation, namely measurement. Measurement is a specific kind of observation; it generates a numerical representation of the phenomenon under investigation, which is often the kind of information needed for the purpose of policy deliberations.

Although mathematical models are not material, they are used as though they are physical instruments. Therefore, standard economic methodology, traditionally focused on theories, is not suitable.2 Standard accounts define models in terms of their logical or semantic connections with theories,3 and methodology is traditionally seen as a way to appraise theories. Instruments (models) are not theories and therefore should be assessed differently. A methodology needs to be developed that is able to assess how mathematical models function. The aim of this monograph is to construct and refine such a methodology. To do this we investigate a variety of economic research practices in the twentieth century, an epoch that has seen the emergence of macroeconomics, econometrics, and the combination, macroeconometrics. In this way, we hope to gain better understanding of what economists achieve by building models and applying these instruments.

We elaborate on Margaret Morrison and Mary S. Morgan’s (1999) account of models. According to their account, models must be considered as one of the critical instruments of modern science. Morrison and Morgan demonstrated that models function as instruments of investigation helping us to learn more about theories and the real world, because they are autonomous agents: that is to say, they are partially independent of both theories and the real world. We can learn from models because they can represent either some aspect of the world, or some aspect of a theory. The intended elaboration is limited to empirical models, that is, those models that inform us about the world.

Despite the fact that models function as physical instruments in economics, they cannot be assessed as such. One usually associates the word instrument with a physical device, such as a thermometer, microscope or telescope. However, the instruments of economics–models–are not material objects, they are mathematical objects. The absence of materiality means that the physical methods used to test material instruments, such as control and insulation, cannot be applied to models.4 This means that we cannot easily borrow from the philosophy of technology, which is geared to physical objects. Models, being ‘quasi-material’ objects belonging to a world in between the immaterial world of theoretical ideas and the material world of physical objects, require an alternative methodology.

In several accounts of what models are and how they function, a specific view dominates. This view contains the following characteristics. Firstly, there is a clearcut distinction between theories, models and data, and secondly, empirical assessment takes place after the model is built. In other words, the contexts of discovery and justification are disconnected. An exemplary account can be found in Hausman’s The Inexact and Separate Science of Economics (1992). In his view, models are definitions of kinds of systems, and they make no empirical claims. Although he pays special attention to the practice of working with a model–i.e. conceptual exploration–he claims that even then no empirical assessment takes place. ‘Insofar as one is only working with a model, one’s efforts are purely conceptual or mathematical. One is only developing a complicated concept or definition’ (Hausman 1992: 79). In Hausman’s view, only theories make empirical claims and can be tested. Above that, he doesn’t make clear where models, concepts and definitions come from. Even in Morgan’s account ‘Finding a satisfactory empirical model’ (1988), which comes closest to mine and will be dealt with below, she mentions a ‘fund’ of empirical models of which the most satisfactory model can be selected.

This view in which discovery and justification are disconnected is not in accordance with several practices of mathematical model building. What these practices show is that models have to meet implicit criteria of adequacy, such as satisfying theoretical, mathematical and statistical requirements, and be useful for policy. So in order to be adequate, models have to integrate enough items to satisfy such criteria. These items include besides theoretical notions, policy views, mathematical concepts and techniques, analogies and metaphors and also empirical data and facts. So, the point of departure for a methodology of models is that the context of discovery is the successful integration of those items that satisfy the criteria of adequacy. Because certain items are empirical data and facts, justification can be built in.

The process of model building

Models are built by fitting together elements from disparate sources. To clarify the integration process, it is very helpful to compare model building with baking a cake without having a recipe. If you want to bake a cake and you do not have a recipe, how do you take the matter up? Of course you do not start blank, you have some knowledge about, for example, preparing pancakes and you know the main ingredients: flour, butter, raising agent and sugar. You also know what a cake should look like and how it should taste. You start a trial-and-error process till the result is what you would like to call a cake: the colour and taste are satisfactory. Model building is like baking a cake without a recipe. A comparable view is expressed by Clive Granger on model building in his study, Empirical Modeling in Economics:

I think of a modeler as starting with some disparate pieces–some wood, a few bricks, some nails, and so forth–and attempting to build an object for which he (or she) has only a very inadequate plan, or theory. The modeler can look at related constructs and can use institutional information and will eventually arrive at an approximation of the object that they are trying to represent, perhaps after several attempts.(Granger 1999: 6–7)

Others (e.g. Stehling 1993) compared model building with ‘basteln’–tinkering –to denote the ‘art’ of model building. The reason that I prefer the analogy of baking is that one of its characteristics is that in the end product you can no longer distinguish the separate ingredients; they become blended and homogeneous.

In a model, the ingredients are theoretical ideas, policy views, mathematical concepts and techniques, metaphors and analogies, stylised facts and empirical data. Integration takes place by translating the ingredients into a mathematical form and merging them into one framework. This idea of mathematics as homogeniser and harmoniser can be clarified by enlarging on the metaphor Morrison and Morgan (1999) use for the function of models, namely as mediator. The mathematical forms that are entered in a model are the result of painstaking negotiations. One could see it as a meeting at which various parties need to come to an agreement. They have little in common and are characterised more by their differences than their similarities, so they are highly suspicious of each other. An impartial mediator is needed to bring the parties involved closer together, step by step, carefully formalising each result in the negotiations. The development and selection of appropriate formulations is part and parcel of the process and it cannot be determined beforehand.

To help elucidate the role of mathematics in modelling, let us take a closer look at how models are built. We are going to look first at two cases of model building. The first case is a business-cycle model, which is considered to be the first mathematical business-cycle model in the history of economics.5 The second case is one of the rare exemplars of a material model in economics, namely Phillips’ hydraulic machine (discussed in Morgan and Boumans, 2004).

Case 1: Kalecki’s business-cycle model

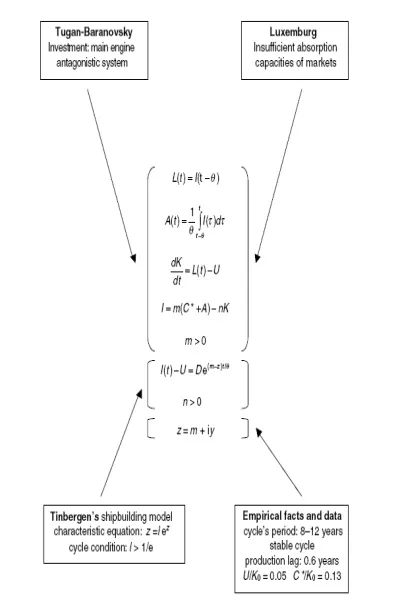

Michal Kalecki’s (1899–1970) mathematical business-cycle model first appeared as ‘Proba teorii koniunktury’ in 1933.6 This Polish essay was read in French as ‘Essai d’une théorie des mouvements cycliques construite à l’aide de la mathématique supérieure’ at the Econometric Society in Leiden in 1933. Its essential part was translated into English as ‘Macrodynamic theory of business cycles’, and was published in Econometrica in 1935. A less mathematical French version was published in Revue d’Economique Politique, also in 1935. The English paper was discussed in Tinbergen’s survey of quantitative business-cycle theories (1935b), appearing in the same issue of Econometrica. The model ingredients are summarised in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Kalecki’s business-cycle model. The figure shows Kalecki’s model as the inte...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 A New Practice

- 3 Autonomy

- 4 Design of Experiments

- 5 Measurement

- Appendix 1 Output–Inflation Tradeoffs

- Appendix 2 Filters

- 6 Rigour

- 7 Conclusions

- Notes

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access How Economists Model the World into Numbers by Marcel Boumans in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.