![]()

1

Transition, involution, or evolution

Rethinking the political economy of China’s industrial reform

Most conventional narratives on the political economy of China’s industrial reform depict a highly decentralized system which has become increasingly open, market-oriented, and based upon competitive, small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The institutional development of China’s industrial governance over the past three decades is often conceptualized as a single, uniform process of ‘transition’ which, from an idiosyncratic starting point, steadily converges towards the global standard practices, rules and governance forms. In this portrait, compared with the Soviet Union and East European pre-socialist countries, China’s ‘transition’ has been gradual and experimental, but it nonetheless adheres to the same principle of liberalization, marketization, and ultimately privatization. Above all, it has been argued, ‘one could be forgiven for believing that the Reagon or Thatch-erite revolution found its truest adherents in socialist China’ (Steinfeld, 2010: 8).

This study shows that the received neoliberal ‘transition’ model of China’s industrial reform is partial and misleading. At the empirical level, it fails to account for the crucial policy and institutional development in China’s industrial governance since the early 1990s, namely the central bureaucracy’s persistent ‘national champions’ industrial policies in nurturing selected large state enterprises, and the making of a batch of centrally controlled big business (henceforth ‘CCBB’, referring to the large business groups and financial institutions under the central bureaucracy’s control) as the so-called ‘national team’ in China. At the conceptual level, this study suggests that the neoliberal ‘transition’ narratives are built upon incomplete and problematic understanding on the institutions that coordinates the indigenous industrial development in China, as well as the path dependence and evolutionary possibilities of these institutions in the era of globalization.

China’s industrial governance during the reform era is not a single, uniform ‘decentralized structure’, but a complicated combination of a distinct, centrally controlled system on the one hand, and a multi-layer, regionally-decentralized system on the other hand. The two subsystems have been interwoven under a common national framework, which is maintained by the party and state. While the exact boundaries between them have often been blurred and shifted over time, their political–economic distinctions remain solid. However, preoccupied with regional decentralization, conventional ‘transition’ narratives have largely ignored the persistence and adaptability of the centrally controlled system in China’s industrial governance during the reform era.

This study aims at providing an alternative picture of the political economy of China’s industrial reform by examining the emergence, composition, and adaptation of this centrally controlled system in governing the ‘commanding heights’ of the Chinese economy. Termed here as China’s centralized industrial order, this system has been constructed and maintained around the very core of the party and state authorities since the 1950s. It can be dissected into four closely interlocked components, i.e., the central technocratic bureaucracy, targeted spheres of industrial assets and enterprise units, the nomenklatura control of Chinese Communist Party (henceforth CCP or the Party), as well as the centrally controlled financial system. This study shows how CCP technocratic bureaucrats have recomposed China’s centralized industrial order since the 1980s, with the traditional Stalinist central industrial ministries and mono-bank system transformed into a group of big business under the central administration’s control. Through an adaptive process of learning, experimentation, and restructuring, the key institutional components and authority relations of China’s centralized industrial order have been consolidated rather than dismantled.

In this study, the organizational and institutional forms that constitute industrial governance, including how the institution of ‘firm’ itself is defined in China’s centralized industrial order, are viewed as evolving historical outcomes, rather than fixed settings, of the purposive actions of CCP bureaucrats as well as the conflicts involving them during the reform. By doing so, this study emphasizes the co-evolutionary process of institutions and actors. Historically constrained but not determined, actors at different levels can creatively combine existing institutional arrangements and resources with new rules, practices, and governance forms. Contrary to the conventional ‘transition’ narratives which portray China’s industrial reform as a single, unitary, decentralization-driven trajectory towards certain predestined ‘end-state’, this study points to a picture in which China’s industrial reform is a diverse, multi-subsystem process in which the centralized industrial order can adapt and develop following its own distinct logics.

Conventional neo-liberal narratives of China’s reform: ‘Market transition’ as institutional convergence

The evolution of China’s economic governance in the reform era is often characterized as a gradual, but steady ‘transition’ process from a set of idiosyncratic institutions built upon the ideology of central planning and ‘leap-forward’ development strategy to an increasingly standard, neo-liberal type system dominated by market institutions (Tian and Liang, 1999; Qian, 1999, 2000; Qian and Wu, 2000; Lin et al., 2003; Wu, 2005; Naughton, 2006; Steinfeld, 2010). In these narratives, the process of China’s ‘transition’ can be experimental and have temporary setbacks, i.e., ‘crossing the river by groping for stones’, but its ‘end-state’ has been preordained – the supposed global norms of ‘modern market economy’ as ‘the other bank of the river’. Among this literature, China’s ‘transition’ is often viewed as no more than the establishment of a free and competitive enterprise system by changing the government–business relationship to an arm’s-length type (Qian and Wu, 2000).

Depending on different emphases,1 conventional accounts following the neo-liberal ‘transition’ model have described China’s industrial reform as a single unitary trajectory characterized by ‘the retreat of state, the advance of market’, ‘the separation of government from enterprises’, ‘the retreat of the state-owned sector, the advance of the private sector’, or ‘the demise of large enterprises in comparative advantage-defying industries, the rise of SMEs in comparative advantage-following industries’. Despite their difference, most ‘transition’ narratives agree that the late 1980s and early 1990s marks a turning point in China’s economic governance since which the market-oriented reform has gained further momentum and become progressively comprehensive, with the market rolling back the state, and the private enterprises rolling away state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which are favoured and protected by the state. Allegedly, China’s industrial reform has entered into an era of grand neoliberal institutional convergence. As Steinfeld (2010:63) remarks on this period: ‘China was indeed crossing a river, but now, the focus shifted from the crossing itself to the bank waiting on the other side: the market. And it was not only the market in the abstract, but rather the market as represented concretely and tangibly by the world’s wealthiest advanced industrial economies.’ In particular, around China’s WTO entry in 2001, it was widely predicted that despite the rule of communist party, China’s government-business relationships will converge towards an ‘arm’s-length type’ as the norm of ‘modern market economy’ (Tian and Liang, 1999; Qian and Wu, 2000).

‘National champions’ industrial policy, Chinese style

A closer look at the process of China’s industrial reform reveals that that a crucial aspect of it clearly defies the narratives and predictions of the neoliberal ‘transition’ model. Instead of changing the government-business relationships towards an ‘arm’s-length type’, the period since the early 1990s has witnessed China’s persistent ‘national champion’ industrial policy to nurture selected large state-controlled enterprises. Such efforts had been highly visible right from the start of this period when Jiang Zemin and Li Peng were elevated to the top leadership at the end of 1980s. It later developed into the ‘grasping the large, letting go of the small’ strategy in the middle 1990s, which aimed at building indigenous, internationally competitive ‘large corporations, large business groups’ by various policy measures. The Asian financial crisis and China’s WTO entry did not weaken this goal and related practices. Instead, the central bureaucracy under Jiang Zemin’s presidency and Zhu Rongji’s premiership (1998–2003) strengthened its efforts to consolidate the core of China’s existing industrial ministries and banking system into a batch of large, centrally controlled business groups and financial institutions, and actively nurtured the domestic dominance and international competitiveness of this group of emerging ‘centrally controlled big business’ (CCBB). The new central administration since 2003, under Hu Jintao and Wen Jiaobao’s leadership, not only continued along this direction of state-led industrial restructuring, but also promoted with even more vigour CCBB’s further consolidation and development.

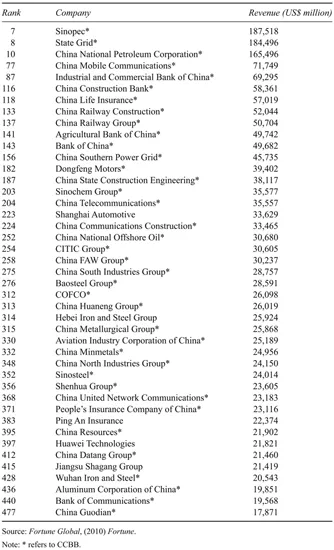

To illustrate the significance of this policy and institutional development, Table 1.1 shows that there are a total of 43 large firms from Mainland China entering the rank of the Fortune Global 500 in 2009 in terms of revenue, among which 40 are large state-controlled firms, 38 are CCBB as members of ‘the national

Table 1.1 Large firms from Mainland China in the Fortune Global 500, 2009

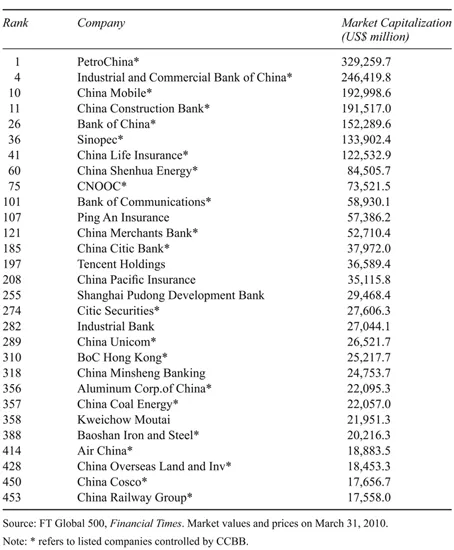

Table 1.2 Large listed companies controlled by firms headquartered in Mainland China, FT Global 500,2010

team’ (apart from 8 large financial institutions, 30 are non-financial CCBB as members of the so-called ‘yangqi’ under the supervision of the State Asset Supervision and Administration Commission, henceforth SASAC). Table 1.2 shows that there are in total 29 large listed companies controlled by the Mainland Chinese firms entering the rank of the FT (Financial Times) Global 500 in 2010 in terms of market capitalization. Among them, 23 are listed subsidiaries controlled by CCBB. Under persistent industrial policy efforts and state-orchestrated restructuring, each of these CCBB occupies a leading position in China’s domestic markets in their business areas and many of them, such as Sinopec, China State Construction Engineering Corporation, Aluminum Corporation of China, Bank of China, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, and Baosteel Group, are building significant operations outside China, going increasingly global.

At the end of 2009, there were a total of 123 ‘yangqi’ or non-financial CCBB (whose main business areas do not include financial services) under SASAC’s supervision. They have a combined asset of around 21.1 trillion RMB, combined revenue of 12.6 trillion RMB, and combined net profit of 597 billion, occupying the ‘commanding heights’ of the perceived ‘lifeblood’ sectors in China such as oil and gas, defence, power generation, chemicals, heavy machinery, telecom, automobile, coal mining, railway, ocean shipping, and aviation (SASAC, 2010). As leading financial CCBB directly controlled by the central authorities, the Big Four banks (Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, Agricultural Bank of China, Bank of China and China Construction Bank) had a combined total asset of over 45 trillion RMB, well over 40 per cent of China’s total financial assets in 2010 and had a combined net profit of around 499 billion RMB in 2010 (PBOC, 2011, company data). Indeed, by the late 2000s, CCBB’s dominant status in the landscape of Chinese business institutions had become plain for all to see.

However, apart from a handful of pioneering studies,2 the literature has largely ignored the significance of this aspect of China’s industrial reform. The specific policies and institutional arrangements involved in this process are often regarded merely as vestiges of the central planning system which would soon be washed away in further market ‘transition’. For example, considering the central bureaucracy’s industrial policy to target the perceived ‘pillar industries’ and support selected large SOEs in the 1990s,3 World Bank (1997:39) argues that ‘it is difficult to say what this policy really means’ and concludes that ‘it is quite likely they work at cross purposes and in unintended ways that distort development’. With regards to Chinese government’s corporate control over targeted large SOEs, Qian (2001) interprets it as a second-best transitional arrangement which will soon be removed as the market reform deepens.

Such presumptions have led to considerable mischaracterization of the nature and policy processes of China’s industrial reform during the recent two decades: when the central government implemented the strategy of ‘grasping the large and letting go of the small’ in the late 1990s, the policy focus was clearly on ‘grasping the large’, i.e., concentrating the resources and policy support on targeted large state-controlled enterprises by allowing the privatization of local small and medium-sized SOEs (Wang, 1998; Huang, 2008).4 As Wu Bangguo, then Vice Premier of China’s State Council, remarked:

The significance of grasping well these 500–1000 core large enterprises, lies not only in that these enterprises themselves played a critical role in the national economy of our country, but also in that as the performance and economies of scale of these core enterprises further improve, they can bring along a large system of enterprises through asset linkages as well as the promotion of industrial and enterprise organizational restructuring, thus creating adjustment space for those inferior enterprises’ closing down, suspension of operation, merger with others or shifting to different lines of production. As a result, by promoting the rolling development of the 500–1000 large enterprises, the entire SOEs sector can also be gradually revitalized.

(Zhao, 1999)

However, the neoliberal narratives of China’s industrial reform tend to focus exclusively on the ‘letting go of the small’. It was claimed that the true significance of China’s industrial restructuring strategy was not about the 1,000 enterprises, but the 1,001st enterprises, i.e., the permission of ‘letting go’ the sea of small and medium sized SOEs outside the range of the designated 1,000 large ones (Chen, 2004; Wu, 2010). Tian and Liang (1999) argue that the strategy of ‘grasping the large’ is a measure of controlling the pace of privatization and concluded that ‘unless privatized, the SOEs have no chance of surviving’, and ‘controlling the big and releasing the small’ is going to ‘pave the way for eventual reform of the large-sized SOEs’ (Tian and Liang, 1999:81).

Now over a decade since ‘grasping the large and letting go of the small’ was formally initiated, despite changes in specific instruments, the central bureaucracy has only persisted in and strengthened its ‘national champions’ industrial policy. Despite being predicted as increasingly obsolete in a system dominated by market institutions and required to exit from corporate governance, the Party and central government have firmly maintained the majority ownership and control on targeted CCBB. Allegedly as ‘having no chance of surviving’, CCBB have apparently strengthened domestic dominance and international competitiveness under the state’s support and control. In sum, instead of converging towards an ‘arm’s length type’ state–business relationship, a crucial part of China’s industrial system has experienced a path of evolution defying the conventional narratives built around the ideas of neoliberal market transition and institutional convergence. It had become increasingly clear by the late 2000s that the neo-liberal ‘transition’ model is misleading in portraying China’s industrial reform as a unitary, convergence story.

Regional decentralization and the hypothesis of China’s industrial governance as a single, giant ‘M-form’ organization

Underlying the problematic understanding of reality are theoretical weaknesses. A series of research since the early 1990s has popularized the now-conventional view that China’s industrial reform is driven by decentralization and the experimentation, imitation and competition among various levels of local authorities (Qian and Xu, 1993; Shirk, 1993; Montinola et al., 1995; Qian and Weingast, 1996; Cao et al., 1999; Maskin et al., 2000; Qian et al., 1999, 2006b; Jin et al., 2005; Krug and Hendrischke, 2008; Zhang and Zhou, 2008; Xu, 2011). Pioneering this literature, Qian and Xu (1993) argue that in contrast to the Soviet Union and Eastern European countries which were dominated by a centrally controlled, planning-based, ‘branch’ industrial ministries system, China’s industrial governance has been dominated by a highly decentralized, multi-layer-multi-regional organizational structure since the end of 1950s. Borrowing the terms ‘U-form’ and ‘M-form’ from Williamson (1975; 1985) but with different definitions, Qian and Xu (1993) argue that each of the former command economies in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union was organized as a gigantic U-form (or the so-called ‘branch’/tiaotiao organization) where SOEs were subordinated to a number of specialized, functional central industrial ministries, while Chinese economy is primarily organized as a gigantic M-form (or the so-called ‘block’/kuaikuai organization) on a regional basis which comprises multi-layer local authorities (provinces, prefectures, counties, townships and villages) and regional industrial systems that are relatively self-contained in terms of production capacity. They argue that it is this M-form structure that have provided the institutional flexibility for China’s ‘market transition’ and driven the rise of local non-state enterprises as well as the continuous deepening of marketization, liberalization, and privatization. Being further expanded, these studies have stimulated a major literature: among others, they have developed into now widely-held theses s...