![]()

1 The Korean economy

Triumphs, difficulties, and triumphs again?

MoonJoong Tcha, Minsoo Lee, and Chung-Sok Suh

1.1 Prologue

Why is it that the Korean economy is so interesting to observe, investigate, and analyse? One of the first images of Korea frequently encountered by foreigners might be those images that they see frequently in newspapers or on TV; involving workers and university students wearing face masks violently demonstrating on the street, throwing Molotov cocktails, or, just as likely, of images depicting riot police even more violently subjugating the demonstrators. However, another common image of Korea, which makes it particularly interesting, reflects the widespread perception that it is one of the few countries that have achieved dramatic economic growth; and more recently, has been hit severely by economic crisis. Korea belonged at the forefront of a group of countries labelled ‘miraculous’ by Lucas (1993), at least until 1997. From being one of the poorest countries in 1961, it had grown by 2001 to be the thirteenth largest economy in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) in the world, notwithstanding the setbacks experienced as part of its recent economic crisis. It is hard to investigate the successes and failures of this remarkable economy in a single chapter. Consequently, in this chapter, we will briefly summarize the triumphs and difficulties that this country experienced on the path to growth.

1.2 From nothing to something

1.2.1 Overview

Korea was historically one of the poorest countries in the world endowed with a small landmass, scarce natural resources, and a large population. Added to this, by the time the Korean War (1950–53) ended the entire peninsular had been completely devastated. During the period from 1953–61, Korea made a very slow recovery from the war, and per capita income was lower than that of most of its neighbouring countries. With the introduction of the first Five-Year Plan in 1962, initiated and designed by the military government, Korea accelerated its development and changed the trend curve of economic growth dramatically. It continued its rapid economic growth in the 1970s, in spite of the downturn of the world economy caused by two oil crises. Since then, the Korean economy has been among the most rapidly growing nations over the period, even during the 1980s when the country was in the middle of political turmoil, and generally regarded as one of the most successful developing economies often used to illustrate the superiority of the capitalistic market economies over socialist economies, in particular North Korea. Since the 1980s, it had become known as one of the ‘four little Asian dragons (or tigers)’ together with Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan, although there have been debates in some quarters about the reality of the rapid economic growth of some East Asian countries (see, e.g. Krugman 1994). When Lucas (1993) discussed the main factors of economic growth, he emphasized that the growth achieved by East Asian countries was miraculous for at least three reasons; it was extremely rare throughout the ages that so many economies in the same region recorded such high growth rates continuously for such a long period. A host of studies attempted to identify the main factors that contributed to these economies’ growth. A general consensus was reached that most of these economies had the following common features, in addition to the fast accumulation of production factors that is traditionally used in the neoclassical framework to explain economic growth (e.g. Hughes 1995, Kruger 1997):

1 They actively pursued export-oriented policies.

2 Usually, government intervention in the economy was not excessive.

3 The importance of education was emphasized.

4 And, these economies were able to maintain stable macroeconomic policies.

In addition to these aforementioned common characteristics, the Korean economy had a few more unique characteristics. For example, it was oriented towards conglomerate-oriented growth. Also, its economic growth was more impressive as it achieved such high growth rates even though a significant portion of GDP (or the government’s budget) was reserved for defence. As well as being such a direct cost, the opportunity cost of defence was immense, considering that all the young males had to complete two years or more of military service. Another unique characteristic of the Korean economy, which was one of the most important explanatory factors of the crisis, is excessive government intervention in the financial sector up until the early 1990s, which subsequently caused structural weaknesses in this sector. A more detailed review of the history of economic growth in Korea follows in the next section.

1.2.2 The road to growth

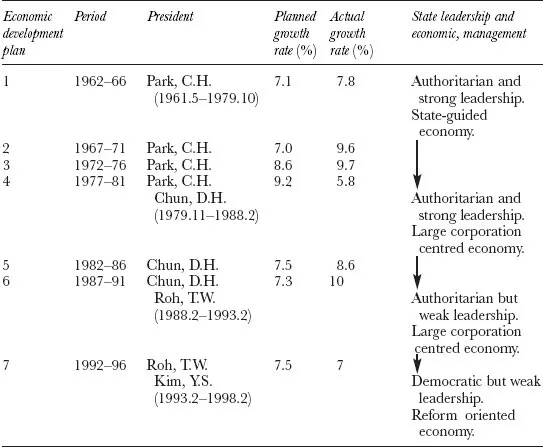

The economic growth of the Korean economy prior to the crisis in 1997 can be categorized into four stages, taking into account the leadership and growth strategies. Table 1.1 summarizes the leadership overall and the development plans, and economic growth for the last forty years. When Mr Chung-hee Park seized power in a military coup and then retained it after holding an election, Korea possessed all the bad characteristics of a typically poor country; a small land mass with an extremely high population density, small domestic markets, no natural resources, and low levels of physical capital. The Five-Year Economic Development Plans initiated by the Park government thus emphasized the role of exports to overcome the limitations imposed by small domestic markets. His government believed that, as Korea was not endowed with abundant natural resources, growth should be achieved by a systematic programme of importing raw materials and intermediate goods for processing, and then exporting commodities with added value. Government policy was in general based on market principles; nonetheless, it used a variety of policy tools, and intensively controlled the banking and financial sectors (World Bank 1993). While the government frequently intervened in the market, it could minimize price distortions and the misallocation of resources caused by intervention, through a system of intensive subsidies. Specializing in labour intensive goods such as clothes and shoes, the economy enjoyed annual economic growth rates of between 8 and 10 per cent throughout the duration of the first two Development Plans until 1971.

Table 1.1 State leadership and economic performance (1961–98)

Source: Rearranged from Kim (2001), p. 14.

As a former General, President Park’s ambition was to build the country to the point where at the very least it would be superior to North Korea in both economic and military power. To this end, the growth achieved in the last decade largely as the product of selling clothes, toys, and wigs was in his eyes not very satisfactory. Moreover, he recognized the importance of economic growth, generated as a result of high value added commodities in the heavy and chemical industries. As a result, the third Economic Development Plan concentrated on developing ‘heavy and chemical industries’ (1973–79) and selected six strategic heavy and chemical industries – steel, petrochemicals, non-ferrous metals, shipbuilding, electronics, and machinery – to receive support such as tax incentives, subsidized public services and preferential financing. In return, the government demanded producers in these areas to strive to achieve international competitiveness. Furthermore, as a means of transferring advanced technology from foreign developed countries to the domestic industries, Park’s government encouraged invitations to many foreign-trained scientists and engineers. Combined with a strong export-driven growth policy, this policy of strategically supporting heavy and chemical industries seemed to be successful, at least in terms of growth. Despite the First Oil Shock, annual growth rates for the first five years reached almost 10 per cent. However, this policy was criticized as well in some quarters, on the basis that this patronage produced, as an inevitable byproduct, a distortion of local industry, particularly in regards to a severe distortion in the structure of domestic industry. Labour intensive firms and small- and mediumsized firms were starved of credit; large firms started to entertain flawed ideas as to ‘the survival of the fattest rather than the fittest’ and accrued excessively high levels of debt. The links between business and government got stronger and rent-seeking behaviour became more common. Moreover, after the two oil shocks, high oil prices pushed the capacity utilization ratio very low, which caused inefficiencies in the heavy and chemical industries where a large amount of capital was initially invested. As a result, during the period of the fourth Economic Development Plan, the annual growth rate sharply declined to about 6 per cent, which was generally viewed by members of the country as indicative of the economy being in recession.1

In 1979, the bureaucrats recognized that the complexity of the economy was in excess of the government’s management capacities, and consequently introduced more market-oriented policies and deregulations. Government intervention continued, however, it focused on restructuring distressed industries, supporting the development of technology, and promoting competition (Kim 2001). While the economy experienced a period of political turmoil following Mr Park’s assassination (in 1979), and the ascension to power of Mr Doo-hwan Chun, bureaucrats liberalized the country even further and used a variety of incentives to encourage production and exports. Favourable international economic environments such as low energy costs, low interest rates and a strong Japanese yen, helped the economy to recover from the relatively poor rates of growth that emerged in the late 1970s, and the economy was able to record growth rates of 9–10 per cent until the early 1990s. However, the non-competitiveness of the financial sector (resulting from excessive government intervention) as well as large-scale levels of private sector debt continued, which later became major sources of economic crises.

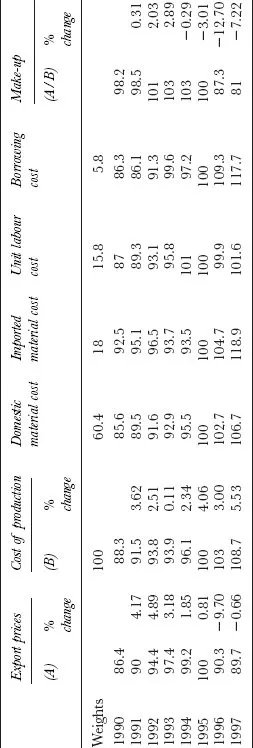

Kim (2001) points out that while the macroeconomic indicators looked fine, the backbone of the economy began to fall apart when President Tae-woo Roh was in office. One of the important reasons for this was, he argued, that Mr Roh compromised unnecessarily over the demands of the workers, which led to frequent labour strikes and an increase in wages that was higher than increases in productivity. It was unfortunate for Korea also that the next President, Mr Young-sam Kim, did not notice how quickly the economy had become incompetent. Influenced more by his concern over popularity ratings than prudent economic considerations, Mr Kim attempted some large-scale economic reforms, which proved to be failures and only created confusion in an economy that was already weakening. As shown in Table 1.2, Kwack (2001) cited figures to demonstrate the extent to which the economy had lost its competitiveness in the run up to the outbreak of the crisis. While the unit value of exporting goods had been decreasing since 1995, all costs such as material costs, labour costs, and borrowing costs had been consistently increasing.

1.2.3 The Achilles tendon of the Korean economy

Throughout the history of rapid economic growth in Korea, the expansion of industrial capacity has been achieved through the expansion of existing firms rather than through the creation of new firms. This pattern has resulted in the growth of a small number of very large firms, chaebols, leading to a tendency towards high industry concentration. The chaebols in Korea have made a significant contribution to industrialization during the period of rapid economic growth, and they have constituted an important part of the Korean economy. Nevertheless, as well as enjoying a kind of monopolist position afforded by government protection and subsidies, they also sought unrelated diversification, which has resulted in an unnecessary concentration of industries. By the end of 1996, the top five chaebols in Korea accounted for more than 8 per cent of the economy’s GDP.

The government utilized financial instruments to support the chaebols’ activities. The financial intermediary system in Korea has been nationalized or heavily regulated by the government since the 1960s, and most foreign loans have been directed and allocated by the government. The government decided who should receive the policy loans (loans distributed by strategic purposes of government), and most of them were distributed to big conglomerates in the industries targeted by the government. The government loans were subsidized by lower interest rates than the prevailing market rates, and the government implicitly guaranteed to bail out government approved firms through debt cancellation or through granting additional government loans, if these firms ran into financial problems. The government’s policy of rewarding chaebols through granting them preferential access to credit and implicit guarantees surrounding potential bailouts led to an underdeveloped banking system and raised ethical or ‘moral hazard’ problems surrounding the behaviour of the chaebols and financial intermediaries. Financial intermediaries frequently failed to carry out due diligence and analysis, as they felt obliged to follow the government’s guidelines for distributing loans.

The chaebols too often ignored whether or not they were capable of paying back the loan or paid insufficient attention to whether they could get a higher return from their investments than the interest they had to pay on the debts incurred to fund these investments, as they felt that they could rely on another round of government support if necessary. Consequently, the large conglomerates financed through subsidized policy loans, too frequently expanded and made acquisitions by investing in high-risk projects or even marginally profitable projects as has been pointed out by Krugman (1998a).

Table 1.2 Unit values of export prices, production cost, and make-up, 1990–95 (1995 = 100)

Source: Rearranged from Kwack (2001), p.55.

Notes

Domestic material cost = producer; Import material cost = import prices of materials and energy; Borrowing cost = weighted average of commercial banks’ lending rates. Weights used are based on information from the Bank of Korea, input–output table; financial statement analysis. Weight used from 1990 to 1992 are: 57.8 for domestic material cost, 22.3 for imported material cost, 15.1 for unit labour cost, and 4.8 for the cost of borrowing.

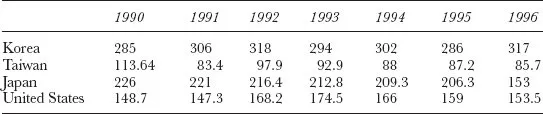

Table 1.3 Debt–equity–asset ratio of manufacturing corporations in Korea, Taiwan, Japan, and United States (%)

Source: Bank of Korea (various years), financial statement analysis.

Given the provision of guaranteed subsidized loans from the government, Korean firms preferred debt financing to equity financing for investment. Consequently, the corporate sector in Korea had a relatively higher debt to equity ratio than many Asian countries, well in excess of 300 per cent, until it faced economic collapse and a fully blown economic crisis (The World Bank 1998, 1999). Table 1.3 indicates that the debt to equity ratio of Korean manufacturing firms was higher than that of Taiwan, Japan, and the United States. Excessive lending to inefficiently operated firms and the mismatching of short-term loans and long-term investments were inevitable as the economy’s financial markets, which had been subject to tight government controls, were liberalized without proper precautionary measures being taken.

The 1990s witnessed the liberalization of financial markets in Korea. Over the period 1993–97, capital flows and foreign exchange...