eBook - ePub

The Human Firm

A Socio-Economic Analysis of its Behaviour and Potential in a New Economic Age

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Human Firm

A Socio-Economic Analysis of its Behaviour and Potential in a New Economic Age

About this book

This book challenges mainstream neo-classical perspectives on the firm. John Tomer argues that in the age of globalization and rapid technological change, an understanding of business behaviour and government policy toward business requires an appreciation of the firm's human dimension. The Human Firm integrates economic analysis with sociological, psychological, managerial, ethical and other interdisciplinary perspectives.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction

Why a theory of the human firm is needed

In an age of global competition and rapidly changing technology and management, understanding business behavior and government policy toward business requires, more than ever, an appreciation of the firm's human dimensions, the dimensions left out of the neoclassical theory of the firm (and its extensions). The Human Firm, through its integration of economic analysis with sociological, psychological, managerial, ethical and other non-economic dimensions of firm behavior, will enable readers to understand aspects of business behavior that are critical to appreciating the new economic age in which we live.

Differences among firms abound. Some firms are adapting well to the new economic realities; in others, economic performance is suffering. Some firms have chosen socially responsible ways which are in harmony with their social and natural environments; others have not. Some firms have adopted strategies and structures allowing them to respond in an integrated, flexible way to change; others have not. Some firms deal with problems requiring decisions in a highly rational way; others do not. Some firms have developed long-lasting, authentic partnerships with their customers; others have not. Some firms, through leadership, create workplaces that elevate their members' lives; others do not. Why do some firms live up to their human potentials while other firms fail to do so? The neoclassical theory of the firm, while useful for understanding markets and allocative efficiency, allows us little insight into these matters. Thus, The Human Firm will focus on (1) what it means for firms to achieve their full potential contribution to society and (2) the typical gap between actual and potential performance. In doing so, this book will integrate the concepts of organizational capital and human capital with the theory of the firm more completely than has been done heretofore.

What do we mean by the word "human" in The Human Firm? First, we do not mean humane. The word humane connotes mankind's capacity to be kind, tender, merciful and sympathetic, and is far too limited for our purposes. The essence of what it is to be human has been considered by the philosopher Mortimer Adler (1985: 161-3). He finds that while actual human conditions and behavior vary greatly around the world, what is common to all humans are the qualities representing our highest human potential, not just our potential for humaneness. These qualities generally correspond to those of a person who could be described as fully human, self-actualized, or psychologically healthy, to use the words of Abraham Maslow (see, for example, Maslow 1971). On the other hand, another important aspect of human nature is fallibility, the propensity to fail to accomplish what could be accomplished and to fail to be what we could be. The analyses of the human firm in this book are designed to help us understand behaviors that represent the highest human potential in a business context as well as behaviors representing the all-too-human failure to realize that potential. In contrast, in neoclassical economics, human behavior in firms is depicted one-dimensionally as economically rational. There is little in the neoclassical literature that reflects the highest qualities of human nature or, for that matter, the lower ones.

Organizational capital

To understand more about the proposed theory of the human firm, it is necessary to explain about the essence of the organizational capital concept. Organizational capital is a kind of human capital in which productive capacity is embodied in the organizational relationships among people; it is not simply embodied in individuals, as in the case of human capital deriving from education. Investment in organizational capital means using up resources in order to bring about lasting improvement in organizational relationships, and thereby, improving productivity, worker well-being and social performance. The development of high-quality organizational relationships makes possible and brings out the best in human nature (Tomer 1987).

Precisely because it is embodied in social relationships, organizational capital is also a kind of social capital. Social capital is a term that has been used, typically by economic sociologists, not simply to refer to productive capacity but more generally to denote a resource that enables actors to accomplish their ends (see, for example, Coleman 1988). The firm's social or organizational capital formation reflects (1) the degree to which, and the manner in which, the firm's actors have become socially connected to each other and to the organization as a whole, and (2) the degree to which, and the manner in which, the firm has become connected to society. Emphasizing that organizational capital is a type of social capital helps us bear in mind that economic production processes are inherently social in nature and that the firm is at least partially embedded in society.

Organizational capital can be considered a factor in the production function. In the conventional production function, the potential or maximum output is determined by the endowments of inputs such as land, tangible capital, labor, human capital and the state of technological knowledge. Typically, actual output is much less than potential output; that is, the gap between potential and actual output is typically positive and substantial. This output gap reflects internal inefficiency in firms, or what Harvey Leibenstein has called X-inefficiency. Internal inefficiency comes from slack in production, which reflects such things as low worker effort and best business practices not being used. Actual output can be explained by both the factor endowments and the degree of inefficiency. If it were not for the inefficiency, the actual output produced from these factors would have equaled the potential output.

An enterprise's X-inefficiency reflects the state of its organization and management, that is, the amount and appropriateness or quality of its investment in organizational capital. Thus, organizational capital, a factor heretofore missing, should be included in the corrected production function, A firm's organizational capital endowment is inversely related to its internal inefficiency. This follows from the presumption that firms devote time, energy and resources to changing their organizational relationships in order to decrease internal inefficiency, i.e. to reduce the output gap. The greater this investment in organizational capital, the less the inefficiency. Obviously, in some cases, it may not work out this way if the organizational innovation fails.

The organizational relationships in which businesses and governments invest, like other aspects of reality, are both hard and soft. Hard attributes are tangible, physical, measurable, capable of being expressed in mathematical relationships, visible and explicit. Soft attributes are the opposite to the above and involve less definite, immeasurable and holistic aspects of the world. The right hemisphere of the brain is said to be better at appreciating the softer aspects, and the left hemisphere is better equipped for dealing with the hard aspects. Financial relationships, ownership and organizational structure (hierarchy) are relatively hard; whereas enthusiasm, fairness, kindness, harmony and compassion are relatively soft.

To illustrate the hard and soft aspects of organizations, consider the organizational relationships that are part of the Mondragón producer cooperatives in the Basque region of Spain. A unique feature of Mondragón's organization is their legal structure involving workers' voting rights, their rights to the economic profit, and their rights to the net book value of the cooperative. These are relatively hard aspects. In contrast, Mondragon is also notable for some of its soft qualities such as the spirit of cooperation and solidarity that has been developed in these cooperatives.

To appreciate the nature of organizational capital, it should be noted that the flow of organizational capital investment adds to the stock of organizational capital. Flows, of course, are amounts per time period, whereas stocks are amounts that exist at one point in time. It is useful to distinguish between quantitative stocks and qualitative stocks. Economists have largely concerned themselves with quantitative stocks such as the money supply or tangible capital goods. When, for example, there is a change in the money supply during the year (flow), the money supply at the end of the year (stock) differs from what it was at the beginning. Similarly, annual investment (flow) changes the stock of tangible capital goods (technology given). In the case of quantitative stocks, the flows can be positive or negative, and thus, the stocks can increase or decrease in a fully reversible way.

Similarly, flows change the value of qualitative stocks, but in this case the stocks correspond to human relationships and qualities that change in ways that are at least partially irreversible. When, for example, a person spends money on educational activity (flow), one's stock of human capital involving new human capacities is increased. To the extent that education changes the person's thinking, knowledge or appreciations, the qualitative character of this person has changed irreversibly, hopefully for the better. Whenever technological and organizational change occur, there is an investment (flow) process that changes irreversibly the qualitative stocks of tangible and intangible capital. For example, if the formal organizational structure along with established paths of communication were changed, it would be unlikely that the organization could ever return exactly to its original situation. Presumably, the intangible or human types of capital are less reversible than the tangible types. Economists, I believe, have paid too little attention to the qualitative nature of such stocks, which are important to the functioning of the economy. This is especially true for the soft aspects of these stocks. Because organizational capital is a qualitative stock which has as many or more soft qualities as hard ones, it is easy to see why economists have overlooked it.

From the above, one can begin to appreciate how in a human theory of the firm, the organizational capital concept plays a central role as a unifying concept. It allows us to link hard and soft aspects of organizational relationships to many aspects of the firm's economic and social performance. It allows us to think clearly about organizational innovation, what needs to be done to bring out the highest potential in people, and what role the government might play in this process. Simultaneously, it allows us to think systematically and clearly about organizations, and it fosters the compassionate and loving side of our nature with respect to our attitudes toward people at work. It helps erect a conceptual bridge between, on the one hand, humanistic, intuitive, even spiritual visions of what business firms could be and, on the other hand, the logical, left-brained theoretical apparatus of orthodox theory. Such bridges may make possible more coherent discussions between heterodox and orthodox economists about the nature of the firm.

Towards a new understanding of the firm’s behavior

How does a firm behave when confronted with alternative courses of action? Will the Firm pollute or engage in pollution prevention activity? Will the firm organize itself internally to meet its long-run competitive challenges, or not? Will the firm in its relationship to customers choose to be a long-term partner, or simply choose to be a short-term transactor, viewing each separate sale as the desired end? The models of firm behavior developed in this book provide answers that are in sharp contrast with those of neoclassical economic theory.

The neoclassical model

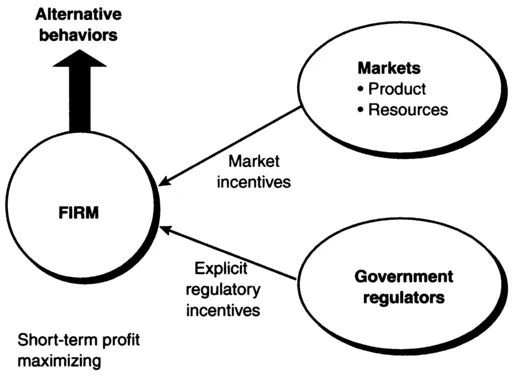

In the neoclassical model, the firm is assumed to have perfect knowledge of alternative courses of action and to choose the alternative that maximizes its current period profit. The neoclassical firm's decision makers are obligated only to the owners, the recipients of profit. External social influences or responsibilities are not a part of this model, nor are internal relationships or ethical considerations. Of course, if the firm fails to consider the external costs (costs imposed on others) of its actions in its decision making, leading to an inefficient resource allocation, the firm may be regulated by governmental entities. The latter may impose explicit regulatory incentives on the firm to counter the problematic market incentives. In this case, the neoclassical firm's behavior will be determined by the combination of market and regulatory incentives. Figure 1.1 depicts these determinants of the firm's behavior.

Figure 1.1 Neoclassical model of the firm's behavior

An overview of the socio-economic model

A general version of the model

This book develops a socio-economic model of the firm's behavior that is quite different from the neoclassical model. The socio-economic model's broad outlines in abbreviated form, i.e. a general version of the model, are considered in this chapter. Later chapters develop more specific, expanded versions of the model, applied to a variety of contexts.

The partially embedded firm

Both neoclassical and socio-economic firms are affected by the same market and regulatory incentives. An important difference between firms in the two models relates to the issue of the firm's embeddedness in society. In early pre-market societies, economic activity tended to be submerged in a particular society's web of social relationships. Here, the behavior of economic organizations was heavily embedded in society. For example, in medieval Europe, the economic exchange between lords and serfs was submerged in the social and political aspects of their situation. In dramatic contrast to this, the neoclassical (N-) firm is an isolated entity, motivated almost entirely by economic considerations. Because the N-firm is minimally influenced by social relationships, it is not embedded in society. N-firms are essentially abstractions in the minds of neoclassical economists; they are not real world firms. Between these extremes is the socio-economic (SE-) firm that is partially embedded in society (Granovetter 1985). SE-firms respond in part to economic incentives and in part to social influences. Such firms respond to the expectation of profit but also act in accord with moral values, commitments to community, and other social bonds and influences depending on the web of socio-economic-political relationships in which they are involved.

To improve their performance, SE-firms may invest in organizational capital, that is, create social relationships that better serve the firm's actors and the firm as a whole. Because of the improved intangible social connections, these actors, while still responding to economic incentives, can be expected to respond more favorably to social influences. These actors are not the detached economic maximizers of mainstream economic theory. Potentially, they are actors who are both constrained by social relationships and effective because of them. When firms invest wisely in organizational capital, they improve both their social responsibility and productivity.

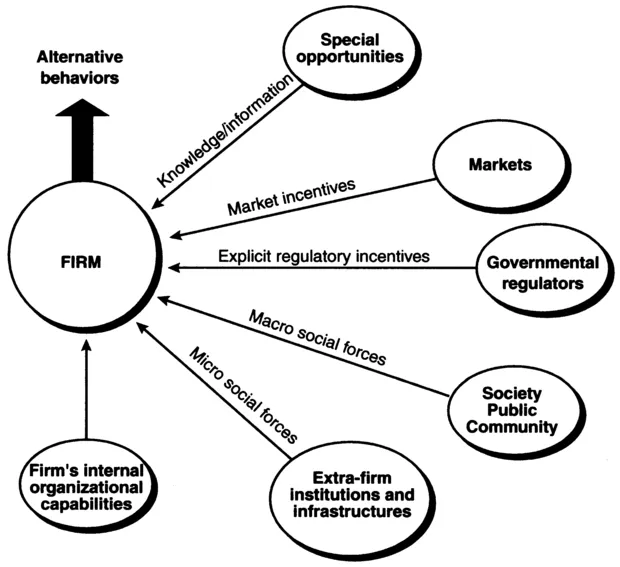

Determinants of firm behavior

In the general version of the socio-economic model in this chapter, the focus is on the most important and general determinants of a firm's behavior. First, as indicated earlier, the SE-firm is affected by market and regulatory incentives. The SE-firm's behavior is also determined by (1) the special opportunities available to it, (2) the "macro" social forces from society, public, and community, (3) the "micro" social forces from extra-firm institutions and infrastructures, and (4) the firm's internal organizational capabilities. In essence, the firm's internal organizational capabilities, i.e. its social and organizational capital, determine the firm's capacity for successfully taking advantage of opportunities for economic gain while honoring its social obligations. The two external social influences, macro and micro, are often crucial insofar as they either encourage or discourage the firm's efforts to achieve its potential performance. Figure 1.2 depicts these basic features of the general version of the socio-economic model. The model's determinants of firm behavior are considered in more detail below.

Special opportunities are known or knowable developments of which firms can take advantage to improve their economic, social or political situation. These could include new technologies, new managerial knowledge, new consumer behavior or attitudes, new government regulations and so on.

Figure 1.2 General version of the socio-economic model of the firm's behavior

The macro social forces, the first of the two external social influences, reflect broad community and societal influences, and thus, high level norms and moral values. They also reflect the public's awareness, concerns, goals and demands. These macro social forces tend to encourage behavior and innovation in society's overall interest, but tend to be diffuse in their impact. One example in the U.S.A. is public attitudes in favor of environmental conservation and against industrial pollution. These have become a significant influence on businesses.

The micro social forces, on the other hand, are those that o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- About the author

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction

- PART I Embeddedness and organizational capital: applying two key concepts

- PART II Competitiveness: rational decision making, flexibility and integration, and leadcrship

- PART III Responsibility in relationships with stakeholders: community, employees, customers and government

- PARI IV Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Human Firm by John Tomer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.