![]()

Part I

Overview of the transatlantic relationship post-World War II

![]()

1 | A shift in transatlantic diplomacy Framing essay Brian M. Murphy |

After World War II, the transatlantic relationship that developed between the United States and Western Europe confronted a communist bloc of countries, spearheaded by the Soviet Union, in what became known as the Cold War. In the long run, the Western alliance exhausted the economic and military capabilities of the communist nations. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 signaled the collapse of Soviet-style government and the triumph of transatlantic values.

The victory, however, did not mean transatlantic diplomacy survived intact because the end of the Cold War failed to create a clear geo-political framework. The “New World Order” announced by President George H. Bush in 1991 remains new but with little order. This situation is not surprising in light of the sudden and unexpected disintegration of the Soviet bloc that caught the transatlantic relationship unprepared to shift into a different pattern after the “balance of power” dynamic (west versus east) ceased to have relevance. The absence of a mutually agreed upon threat has frustrated the effort to revitalize and refocus transatlantic cooperation. As former Israeli Prime Minister Simon Perez once stated, “When you lose your enemy, you lose your foreign policy” (Lamassoure, 2011). Without a compass, responses to global events have become little more than reflexive reactions to immediate dangers. The US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 shattered any illusion of transatlantic solidarity in dealing with the new world order and a series of subsequent crises have only served to highlight divergences across the Atlantic. In this environment, there is a possibility that the partnership may outlive its usefulness in anchoring global diplomacy in the post-Cold War era. A review of the relationship’s complex history provides background and context for formulating an understanding of the current status of the relationship.

European integration and the United States

Proposals to unify Europe by peaceful means have a long history, but the devastation caused by World War II catalyzed momentum to embark on the process with a newfound commitment. The effort lacked high-profile leadership until Winston Churchill in 1946 – then out of office – called for “recreating the European family” by building a “kind of United States of Europe” (Wunderlich, 2007: 57). Churchill’s plea led to the 1948 Congress of Europe that assembled representatives from 16 nations. The result was the creation of the Council of Europe, an organization that has grown from ten member nations to 47 today. Except in the area of human rights, however, the Council has failed to achieve many significant accomplishments, largely because its recommendations are without legal force. Historically, it can be looked upon as the first step toward continental collaboration but, in practical terms, it did not provide a strong enough foundation to address the problems shared in common.

Significantly, the push for more genuine coordination among European nations came from the United States. A series of factors convinced the United States to encourage deeper integration: (1) Europe was too weak on its own to stimulate the economies of its countries and poverty was threatening postwar stability; (2) popular dissatisfaction with economic conditions was causing a turn to pro-Soviet parties, with communists earning significant proportions of the vote in France and Italy; and (3) the United States was requiring consumers to export its goods in order to sustain its own economic health and Europe was the only region in the world developed enough to serve as an overseas market (see generally, McCormick, 2011: chapter 3).

Yet the most important reason the United States promoted the integration of Western Europe was to solve its key security concerns after World War II. President Harry Truman embraced what Geir Lundestad has labeled a “double containment” strategy (Lundestad, 2005: 38). On the one hand, the United States wanted a barrier against expansion of the Soviet Union after Eastern Europe had fallen behind the “Iron Curtain.” Russia had to be stopped from enlarging its sphere of influence and, since it currently bordered on Western Europe, the line had to be drawn at this point. On the other hand, the US needed a way to prevent Germany from becoming a future aggressor again. The US was already hearing grumblings from governments in Europe that wanted revenge against Germany for its actions in the war. President Truman had to find a means to make Germany’s neighbors willing to accept it without punitive retaliation while, at the same time, assuring Germany that it no longer had to fear from its former enemies.

In 1947, US Secretary of State George Marshall announced the European Recovery Program, commonly called the Marshall Plan, in which the US promised to provide direct grants – not loans – on two conditions: (1) European governments collaborated in dispersing the funds and (2) all European countries affected by the war, east and west, would be eligible to participate. In other words, no money could be spent unless all countries cooperated. This requirement not only planted the seed of European integration, but also meant that Germany’s former adversaries had to welcome it back into the European family of nations in order to receive any money.

The US eventually dispensed $12.5 billion between 1948 and 1951 to countries in Western Europe, with all countries in Eastern Europe declining the invitation under Soviet duress. While the economies in Western Europe experienced dramatic improvement almost immediately, the Marshall Plan had a different impact in Eastern Europe. As explained by William Hitchcock, “The Czech flirtation with the Marshall Plan, combined with his growing fears of American policy in Germany, shocked [Soviet leader Josef] Stalin into adopting a ruthless plan for the immediate consolidation of communist rule in Eastern Europe” (Hitchcock, 2003: 115). The Marshall Plan clearly succeeded in solidifying democracy in Western Europe but it had the reverse consequence in the east. Sides in the Cold War were now defined for the next 40 years.

Europe revived quickly and soon became in position to take control of its own destiny. On May 9, 1950, French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman proposed placing “Franco-German production of coal and steel … within an organization open to the participation of other countries of Europe” (Sutton, 2011: 49). The proposal focused on steel and coal to create joint control over the materials needed for war as well as to pool resources to compete against the US and Soviet Union in industrial production. Six countries – France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands – signed the Treaty of Paris in 1951, which established the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). The US again played a critical role behind the scenes. Germany initially resisted joining the treaty because it involved breaking up cartels that had traditionally dominated steel manufacturing in the country. John McCloy, US High Commissioner in Germany, called the German chancellor to his office and informed him that France and the United States, who occupied the country along with the United Kingdom and the USSR, were prepared to enforce their own “decartelization scheme” if the treaty was rejected (Parsons, 2003: 61). In other words, Germany should accept the Treaty of Paris or the US would break up the steel companies on its own. The ultimatum succeeded in crushing German resistance to the ECSC and European integration took its first tentative step.

The ECSC was founded on August 10, 1952, and operated until 2002. The United Kingdom (UK) opted out because its leaders feared the loss of national sovereignty to an organization that Prime Minister Clement Attlee called “utterly undemocratic and responsible to nobody” (Leffler and Westad, 2010: 172). Britain, in the process, became an outsider in Europe for the next two decades. The initial success of the ECSC inspired discussions in the mid-1950s for further integration on military (European Defense Community) and political (European Political Community) fronts but both efforts collapsed when the French parliament voted against rearming Germany as a condition of defense collaboration. Interest in reviving closer integration was soon restored as several factors served to underscore the vulnerable status of Europe during the Cold War: (1) dependence on the US for nuclear technology hindered development of atomic energy for peaceful purposes; (2) tariff barriers among European nations kept the price of goods costly and the volume of exports low; and (3) military weakness allowed continental foreign policy to be driven, if not dictated, by the Americans.

The latter weakness proved particularly humiliating in 1956 when US President Dwight Eisenhower compelled France and the UK to withdraw their troops from the Suez Canal after it was seized by Egypt. Embarrassed by the inability to defy an American mandate, German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer told French Prime Minister Guy Mollet, “Europe will be your revenge” (Reynolds, 2001: 128). From this point onward, the construction of a united Europe increasingly became a project in which the US was sidelined as a spectator.

On June 1, 1958, the six ECSC countries signed the Treaty of Rome creating the European Economic Community (EEC). The goals of the EEC were the following: (1) to form a “common market” among the membership in which internal tariffs and quotas would be eliminated over a period of time; (2) to establish a mutual external tariff against foreign goods; and (3) to provide agricultural subsidies and price supports to eliminate discrepancies between farmers. These steps, when taken together, helped in restoring European influence in the wider world (Pinder and Usherwood, 2008). The EEC, which eventually absorbed the ECSC, grew larger in terms of both membership and responsibilities. In time, the relationship over the Atlantic increasingly became less onesided in favor of the United States.

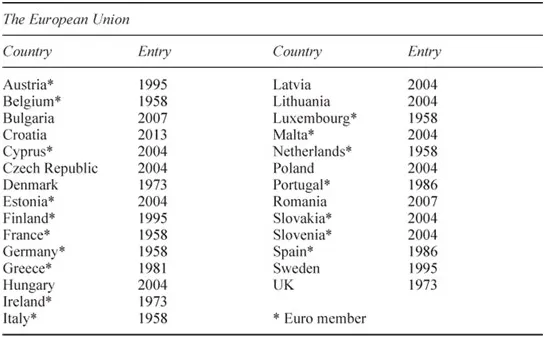

There was never a plan guiding progress toward European integration. Circumstances, mostly unexpected and usually of an urgent kind (e.g., the oil crises of the 1970s), were exploited as opportunities to build more solid connections across the continent. Over the next half century, membership reached 28 countries (see Table 1.1) – with Croatia joining in 2013 – and, at the same time, a series of treaties expanded the EEC’s scope of authority. The Single Europe Act (1987) launched the “single market” in which almost all non-tariff barriers, such as product regulations that blocked goods from entering a country, were eventually removed to enable the free movement of people, goods, and services across national borders. Transportation throughout Europe, for the most part, has become as easy as travel within the United States. The Maastricht Treaty (1992) brought far-reaching reforms that amounted to a fundamental transformation: citizens could vote and hold office in any other member state; a single currency (euro) was proposed; the organization was renamed the European Union (EU); a mechanism for a common foreign and security policy was devised; and greater collaboration on matters of justice and home affairs (e.g., immigration, drug trafficking, customs, international fraud, and terrorism) was promised. The Treaties of Amsterdam (1997) and Nice (2003) assigned additional powers to the EU and made decision-making somewhat more efficient. The euro currency began circulating in 2002 among 12 member states and currently is in use by 17 EU countries. An attempt to consolidate the treaties into a single constitution with a more streamlined administration failed when France and the Netherlands rejected it in 2005, although the Lisbon Treaty (2009) adopted the provisions related to certain leadership positions such as in foreign and security policy.

Table 1.1 List of European Union countries and their entry dates of membership

The European Union has proven capable of exercising considerable influence in world affairs today. Nonetheless, it still has internal challenges to overcome in making its economic and foreign affairs function in a harmonized fashion. Moreover, the organization of the EU remains unwieldy and not independent enough from interference by the member states. This complexity not only confuses its own citizens, but also undermines authority and legitimacy. As former US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright allegedly quipped, “To understand Europe, you have to be a genius – or French.” Despite these concerns, the European Union no longer lingers in the shadow of the United States. The traditional pattern of the relationship across the Atlantic is at a point that warrants re-examination.

The transatlantic relationship

US enthusiasm for deeper European integration became less reliable after the initial honeymoon period during the 1950s. This change in attitude coincided with the emergence of the EEC as an economic powerhouse competing against the Americans for a share of the world market. The Kennedy and Johnson administrations in the 1960s were at first reluctant to confront the EEC for fear of damaging Western cohesion in the Cold War. The oil crises of the 1970s coupled with a severe budget deficit in the US made the corrosion of transatlantic solidarity impossible to mask.

In 1971, President Richard Nixon ended the convertibility of dollars into gold to prevent a possible run against US gold reserves housed in Fort Knox. According to John McCormick, the unilateral decision by the Nixon administration to pull the United States off the gold standard caused European leaders “to argue that Europe needed to unite in order to protect its interests” (McCormick, 2007: 45). The expense of defending Europe was also contributing to the budgetary strain experienced in America but little compromise occurred despite Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s push for European nations to cover more of their own security costs.

The oil crises presented a more serious set of issues. The 1973 war between Israel and Arab countries placed Europe “in the uncomfortable position,” Mark Gilbert has written, “of having to choose between its American ally and the suppliers of what had become since the 1950s its main source of energy generation. The governments of the Nine chose to back the Arabs” (Gilbert, 2003: 135). When US military flights destined for Israel were prohibited from using European bases, President Nixon threatened the withdrawal of American troops from the continent. European nations relented but at the price of added tension in the transatlantic relationship. The Arab–Israeli dispute has continued as a source of friction between Europe and the US to the current time.

Interaction across the Atlantic did not improve any time soon as another controversy was quick to surface. In the late 1970s, the US became alarmed when the Soviet Union decided to update its nuclear arsenal to supplement its already massive troop advantage in Europe. The only feasible solution, from the American perspective, was to replace the country’s long-range missiles stationed in Europe with intermediary ones because such missiles could be tactically used to stall a Soviet invasion until US troops could reinforce the continent. This change in strategy was not well received in Western Europe. Whereas long-range missiles bypassed the continent in any exchange between the US and Russia, Europe itself would become the target of a nuclear attack by intermediary-range missiles. Enormous and often intense demonstrations erupted across Europe in protest during the early 1980s. The transatlantic standoff was defused when German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt broke ranks with his European counterparts upon recognizing that dependence on long-range missiles had failed to achieve headway in convincing the Soviets to negotiate. Schmidt reasoned that a different approach at least had the potential of yielding better results. Germany’s turnaround gave political coverage for other European governments to reverse direction on the issue and the deployment of new missiles began in 1983. The episode, although resolved amicably in the end, contributed to the continuing slide in mutual confidence on both sides of the Atlantic.

The administration of Ronald Reagan in the 1980s had s...