Introduction

When considering the issue of white voters, the first question worth asking is whether or not it even makes sense to lump this massive percentage of the electorate together. Can we speak of the “white vote” in a manner analogous to the “African American vote”? The knowledge that a voter is black provides a tremendous amount of predictive power in terms of that person’s vote choice—in the overwhelming majority of cases, such a voter will support Democrats all the way down the ballot. Latinos and Asians are also quite likely to support Democratic candidates in most circumstances, though in the case of these other minority groups, the support for Democrats is less universal and there is meaningful variation depending on their country of origin—Cuban Americans and Vietnamese Americans are more likely to support Republicans than other Latino and Asian groups, for example.1 Looking nationwide, is there any evidence of racial bloc voting among whites? If not, are there reasons to expect such behavior in the future?

This chapter will examine broad trends in white voter behavior, examining changes in the white vote over time. Beyond vote choice, this chapter will also look at policy preferences among whites, considering whether there are any policy issues on which whites in all states and regions broadly agree. Finally, it will briefly consider those policy issues where whites are clearly distinct from racial and ethnic minorities in their opinions.

Of all the empirical chapters in this book, this is the least methodologically sophisticated. This chapter looks at whites as a group, making no effort to examine sub-categories within that racial group, beyond state-by-state differences. It reveals that whites remain highly divided in terms of party identification, policy preferences, and voting behavior.

Trends in White Presidential Voting

It is neither novel nor controversial to say that whites are the demographic base of the Republican Party. While not all whites are Republicans, and in some states a majority of whites consistently vote for Democratic candidates, the overwhelming majority of votes cast for Republican candidates come from whites. However, white support for the GOP has not been equally strong in all recent elections. Since the 1970s, whites have given different levels of support to Republican presidential candidates.

When we examine aggregate vote choice in presidential elections over the last 30 years,2 we see that white support for the Republican candidate dropped below 50 percent only twice in this period (1992 and 1996). In both cases, the white Republican vote was split by the presence of Reform Party candidate Ross Perot on the ticket. White support for Republicans reached a peak in the 1980s, and two thirds of white voters supported Ronald Reagan in his landslide reelection victory in 1984. George H. W. Bush performed almost as well in 1988.

The strong Republican showing among whites in the 1980s is not surprising, given the GOP’s political fortunes in presidential elections during that period. Ronald Reagan won landslide victories in 1980 and 1984, and George H. W. Bush’s electoral performance in 1988 was equally impressive. The strong performance of Republican candidates among whites in the most recent elections is much more interesting. According to exit polls, Mitt Romney won 59 percent of the white vote in 2012, yet failed to win the presidency. This is only one percentage point less than the share of the white vote earned by George H. W. Bush in his 40-state victory over Michael Dukakis. Not only did Romney perform better than McCain among white voters, but he performed better than George W. Bush in either 2000 or 2004.

We should be cautious before inferring too much from this finding. Although Romney performed quite well among whites who voted, this does not necessarily mean that Romney was more popular among whites in 2012 than Bush was in 2004. Many whites who showed up at the polls for Bush may have stayed home for Romney—the relatively low voter turnout among whites in 2012 indicates this is a strong possibility. Despite that caveat, exit polls do show that much of the GOP’s message continues to resonate with its demographic base. Indeed, had Gerald Ford or George H. W. Bush performed as well as Mitt Romney among white voters, they would have won their reelection bids. With that much support from whites, Bob Dole would have defeated Bill Clinton. Unfortunately for the GOP, strong support from whites is no longer enough to win the presidency because white voters are no longer the overwhelming majority of the electorate that they were in 1976 or even 1996.

Although the GOP has benefited from its slowly increasing share of the white vote, it has increased its support from whites at a rate too slow to overcome the growing minority electorate, which consistently votes heavily for Democrats.

The White Presidential Vote by State

Examining the overall percentage of white votes earned by the two parties nationwide can be an informative exercise, but its value is limited when we consider the enormous state-by-state variation in white voting preferences. Presidential elections are not determined by popular vote, but by states via the Electoral College. Thus white vote choice in presidential elections should also be considered at the state level.

One source of vote choice data by racial group at the state level can be obtained from CNN’s exit poll database.3 As is always the case when considering exit polls, a degree of caution should be exercised when interpreting results. There are well-publicized cases in which exit polls were initially mistaken about an election outcome—in Florida in 2000 and Ohio in 2004, for example. Given the limited sample size, we become less certain about exit polls’ results when considering smaller subgroups within the sample—in this case, non-Hispanic whites. Nonetheless, exit polls are useful tools for political scientists, and we can be reasonably certain in most cases that the true result was within a few percentage points of the estimated results.4 Furthermore, we are presently more interested in broad trends than in perfectly predicting the election outcome in a particular state.

One finding that immediately stands out is the huge variability in the “white vote” as we look across the nation. Nationwide, these exit polls indicate that 59 percent of whites supported Romney; however, the standard deviation when we consider white vote at the state level was an impressive 11.45 percentage points. In Mississippi, it would be only a slight exaggeration to say that presidential elections could be conducted by the Census Bureau, sparing individual voters the trouble of turning out to vote. A huge majority (96 percent) of African Americans in the state voted for Obama, and 89 percent of white Mississippians voted for Romney. On the other hand, 66 percent of white Vermonters voted for Obama. Indeed, even if the franchise in Vermont was restricted exclusively to white men, as was the case in early American history, Obama would have still won almost 60 percent of the vote. There are a handful of other states in which this is true. Obama also won a majority of white men in Washington State, Oregon, Maine, and Massachusetts. Obama almost certainly also won a majority of all major white groups in Hawaii, but there are no available exit poll data for that state.

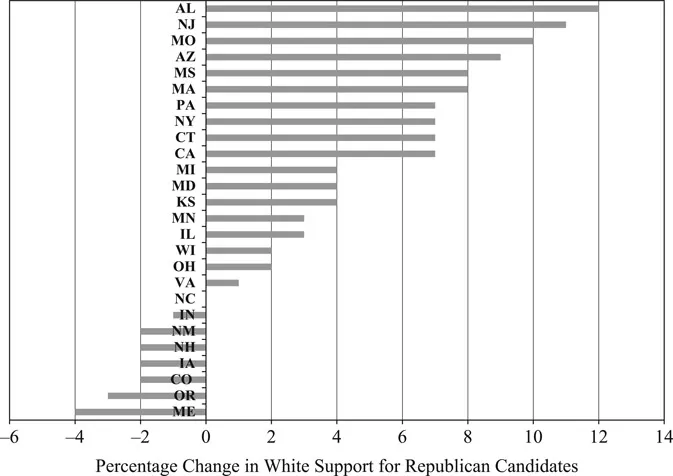

Not every state is included in the CNN exit poll database every year. However, a sufficient number of states have been included since 2000 to see the direction of trends among white voters. It is worth comparing the 2000 and 2012 presidential elections. In both elections, the Democratic candidate narrowly won a victory in the popular vote—though the margin of victory obviously was larger in the latter election. As noted above, however, Al Gore performed better among white voters nationwide than Barack Obama. Of the 26 states with available exit poll data broken down by racial groups in both 2000 and 2012, the mean change in the white vote was 3.57 more percentage points for the Republican candidate in the latter election. The decrease in the Democratic share of the vote was not uniform across the nation, however. Figure 1.1 shows the change in the state-level white vote for which there were available data.

Figure 1.1 Change in White Vote for GOP Candidates in Presidential Elections, 2000–2012 Percentage Change

We see that most states witnessed an increase in the Republican share of the white vote in presidential elections. This was most dramatic in Alabama, where Romney won a remarkable 84 percent of the white vote in 2012, compared to the 72 percent won by Bush in 2000. We see a number of states in which support for Republicans among whites dropped. In Maine, white support for the Republican candidate dropped by four percentage points between the two elections, and in Oregon the drop was three percentage points.

It is interesting how little the states in which whites became more Republican apparently have in common. The two states with the most dramatic change in favor of the GOP among whites were Alabama and New Jersey. Two of the states where whites became less Republican between the two elections were in New England (New Hampshire and Maine) as were two of the states that became more Republican (Connecticut and Massachusetts). The large swing for Massachusetts can surely be attributed to the fact that Mitt Romney was the former governor of that state and Bush performed exceptionally poorly there in 2000. In spite of that impressive improvement among whites in Massachusetts between the two elections, Romney nonetheless lost Massachusetts by a large margin in 2012.

What could explain these changes? With the exception of New Mexico, one attribute that all states in which whites became less Republican have in common is demographic: They are overwhelmingly white. We also see that many of the states in which whites became more Republican were less white than the national average. Indeed, the Pearson’s r correlation coefficient5 for the state-level change in the white vote for Republicans and the percentage of the state-level population that was white as of the 2000 census was a moderate −0.46. That is, the whiter a state was at the start of the 21st century, the smaller the shift within whites in that state toward the Republican Party. In states that were less white in the aggregate, whites, on average, became more Republican. The potential relationship between demographic change and white vote choice will be explored in greater detail in Chapter 7 in this volume.

An equally interesting question is whether white voters are becoming more homogeneous nationwide in terms of vote choice or whether geographic differences remain as important as ever. Of the 26 states for which there were exit poll data in both 2000 and 2012, we see little evidence that geographic differences among white voters are decreasing. According to these exit polls, in 2000 only 34 percent of Massachusetts whites voted for Bush, but 81 percent did so in Mississippi—thus the gap in the white vote between the least and the most Republican states was 47 percentage points. In 2012, only 40 percent of whites in Maine voted for Romney, but 89 percent of whites in Mississippi did so—a gap of 49 percentage points. The standard deviation for these states in 2000 was 10.15 percentage points, but was 11.45 percentage points in 2012. Thus, although the trend nationwide has been toward higher levels of Republican voting among whites, this trend has not been uniform, and voting differences between whites in different states remain large and have even grown. Although the gap remains just as large between the most Democratic state and the most Republican state, the minimum white support for the GOP and the maximum white support for the GOP have both noticeably increased.

White Policy Preferences and Political Attitudes Across the States

There are limits to what we can infer about political attitudes from vote choice alone. After all, the United States does not have two major parties. Instead, there are 50 Republican parties and 50 Democratic parties at the state level, each with their own platforms and candidates. We should not overstate this, as partisan polarization has led to greater homogeneity within the Republican and Democratic Parties, both at the elite level and at the mass level.6 In addition to vote choice, an examination of public policy preferences across the nation may shed light on which issues most divide white voters.

Before examining polarization of the electorate, a critical first step is defining what polarization actually means. How polarization is def...