eBook - ePub

The Future of the Nation-State

Essays on Cultural Pluralism and Political Integration

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Future of the Nation-State

Essays on Cultural Pluralism and Political Integration

About this book

The tension between culture, politics and economy has become one the dominant anxieties of modern society. On the one hand people endeavour to maintain and develop their cultural identity; on the other there are many forces for international integration. How to understand and explain this fundamental issue is illuminated in nine essays by eminent scholars.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Future of the Nation-State by Sverker Gustavsson, Leif Lewin, Sverker Gustavsson,Leif Lewin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Culture

The Nation-State as a Source of Common Mental Programming: Similarities and Differences Across Eastern and Western Europe

The concept of mental programming

“Mental programming” is a computer user’s metaphor for the pattern of thinking, feeling and acting that every person has acquired in childhood, and carries along through life. Without such mental programmes people’s behaviour would be unpredictable, and social life impossible.

A person’s mental programming is partly unique, partly shared with others. We can distinguish three levels of uniqueness in mental programmes:

1. The least unique and most basic is the universal level of mental programming which is shared by all, or almost all, mankind. This is the biological “operating system” of the human body, which includes a range of expressive behaviours such as laughing and weeping, and kinds of associative and aggressive behaviours which are also found in higher animals. This level of our programming has been popularized by ethologists (biologists specialized in animal behaviour) such as Desmond Morris (1968), Konrad Lorenz (1970), and Irenaeus Eibl-Eibesfeldt; the latter has called one of his books “Der vorprogrammierte Mensch” (Man the Pre-Programmed, 1976).

2. The collective level of mental programming is shared with some but not with all other people: it is common to people belonging to a certain group or category, but different among people belonging to other groups or categories. The whole area of subjective human culture (as opposed to objective culture which consists of human artifacts; see Triandis, 1972:4) belongs to this level. It includes the language in which we express ourselves, the deference we show to our elders, the physical distance from other people we maintain in order to feel comfortable, the way we carry out basic human activities like eating, making love, or toilet behaviour and the ceremonials surrounding them.

3. The individual level of human programming is the truly unique part. No two people are programmed exactly alike, not even identical twins reared together. This is the level of individual personality, and it provides for a wide range of alternative behaviours within the same collective culture.

The borderlines between the three levels are a matter of debate within the social sciences. To what extent are individual personalities the product of a collective culture ? Which behaviours are human universals, and which are culture-dependent ?

Mental programmes can be inherited, that is transferred in our genes, or they can be learned after birth. From the three levels, the universal level must be entirely inherited: it is part of the genetic information common to the human species. Programming at the individual level should be at least partly inherited, that is genetically determined. It is otherwise difficult to explain the differences in capabilities and temperament between successive children of the same parents raised in very similar environments. But at the middle, collective level all mental programmes are learned. They are shared with people who went through the same learning process, but who do not have the same genes. For an example think of the existence of the people of the U.S.A. Mixing all the world’s genetic roots, present-day Americans show a collective mental programming very recognizable to the outsider. They illustrate the force of collective learning.

Mental programming manifests itself in several ways. From the many terms used to describe mental programmes, the following four together cover the total concept rather neatly: symbols, heroes, rituals and values. From these, symbols are the most superficial and values the most profound, with heroes and rituals in between.

Symbols are words, gestures, pictures or objects which carry a particular meaning only recognized as such by those who share the mental programme. The words in a language or jargon belong to this category, as do dress, hair-do, Coca-Cola, flags and status symbols. Heroes are persons, alive or dead, real or imaginary, who possess characteristics that are highly prized by those sharing the mental programme, and thus serve as models for behaviour. Rituals are collective activities, technically superfluous to reach desired ends, but considered socially essential: they are therefore carried out for their own sake. Ways of greeting and paying respect to others, social and religious ceremonies are examples of rituals. Symbols, heroes and rituals together constitute the visible part of mental programmes; elsewhere, I have subsumed them under the term “practices” (Hofstede, 1991:7).

Values are the invisible part of mental programming. Values can be defined as “broad tendencies to prefer certain states of affairs over others” (Hofstede, 1980:19). They are feelings with an arrow to it: a plus and a minus side.

The transfer of collective mental programmes through learning goes on during our entire lives. The most fundamental elements, the values, are learned first, when the mind is still relatively unprogrammed. A baby learns to distinguish between dirty and clean (hygienic values) and between evil and good, unnatural and natural, abnormal and normal (ethical and moral values). Somewhat later the child learns to distinguish between ugly and beautiful (aesthetic values), and between paradoxical and logical, irrational and rational (intellectual values). By the age of ten, most children have their basic value system firmly in place, and after that age, changes are difficult to make.

Because they were acquired so early, values as a part of mental programming often remain unconscious to those who hold them. Therefore they can not normally be discussed, nor can they be directly observed by outsiders. They can only be inferred from the way people act under various circumstances.

The transfer of collective mental programmes is a social phenomenon which, following Durkheim (1937 [1895]: 107), we should try to explain socially. Societies, organizations, and groups have ways of conserving and passing on mental programmes from generation to generation with an obstinacy which many people tend to underestimate. The elders program the minds of the young according to the way they were once programmed themselves. What else can they do, or who else will teach the young ? Theories of race, very popular among past generations, were an erroneous genetic explanation for the continuity of mental programmes across generations.

“Collective mental programming” resembles the concept of habitus proposed by the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. Bourdieu (1980: 88-89) describes this concept in words which I translated as follows: “Certain conditions of existence produce a habitus, a system of permanent and transferable dispositions. A habitus … functions as the basis for practices and images … which can be collectively orchestrated without an actual conductor”. The fact that Bourdieu associates collective behaviour with orchestration by a conductor reflects his French national mental programming, to which I will come back later.

Levels of mental programming

Collective mental programming, as I just described it, takes place within the collectivities people are part of. Everybody belongs to different categories at the same time; therefore, everybody carries different levels of mental programming. The most obvious ones are:

- – a family level, determined by the family or family substitute in which a person grew up;

- – a gender level, according to whether a person was born as a girl or as a boy;

- – a generation level, according to the decade a person was born in;

- – a social class level, associated with educational opportunities and with a person’s occupation or profession;

- – a linguistic level, according to the language or languages in which a person was programmed;

- – a religious level, according to the religious tradition in which that person was programmed;

- – for those who are employed, an organizational or corporate culture level according to the way a person was socialized by the work environment;

- – a nation-state level according to one’s country (or countries for people who migrated during their lifetime);

- – within nation-states, possibly a regional and/or ethnic level.

In this chapter I will focus on the level associated with the nation-state. This corresponds partly with what once was called “national character”, and later “national culture”. National characters are intuitively evident, and have been so for hundreds and even thousands of years. However, because of the values element in national mental programmes, statements about national characters were almost without exception extremely biased. They often contained more information about the person making the statement than about the nation the statement was about.

In order to avoid this bias, I will only use comparative information about differences in nation-state-linked mental programmes that treat every nation-state’s data as equivalent.

National culture differences

Human societies as historically, organically developed forms of social organization have existed for at least ten thousand years. Nation-states as political units into which the entire world is divided and to one of which any human being is supposed to belong are a much more recent phenomenon in human history. The concept of a common mental programming applies strictly spoken more to societies than to nation-states. Nevertheless many nation-states do form historically developed wholes even if they are composed of different regions and ethnicities, and even if less integrated minorities live within their borders. This is certainly the case for the nation-states of Central and Western Europe.

Nation-states contain institutions that standardize mental programmes: a dominant language (sometimes more than one), common mass media, a national education system, a national army, a national political system, national representation in sports events with a strong symbolic and emotional appeal, a national market for certain skills, products, and services. Today’s nation-states do not attain the degree of internal homogeneity of the isolated, usually nonliterate societies traditionally studied by field anthropologists, but they are the source of a considerable amount of common mental programming of their citizens.

The German sociologist Norbert Elias has described this process in words which I have translated as follows: “The societal units which we call nations distinguish themselves clearly from each other by the nature of their affect transactions (durch die Art ihrer Affekt-Ökonomie), that is by the patterns fashioning the individual’s affect life under the pressure of institutionalized tradition and of the actual situation” (Elias, 1969:40-41).

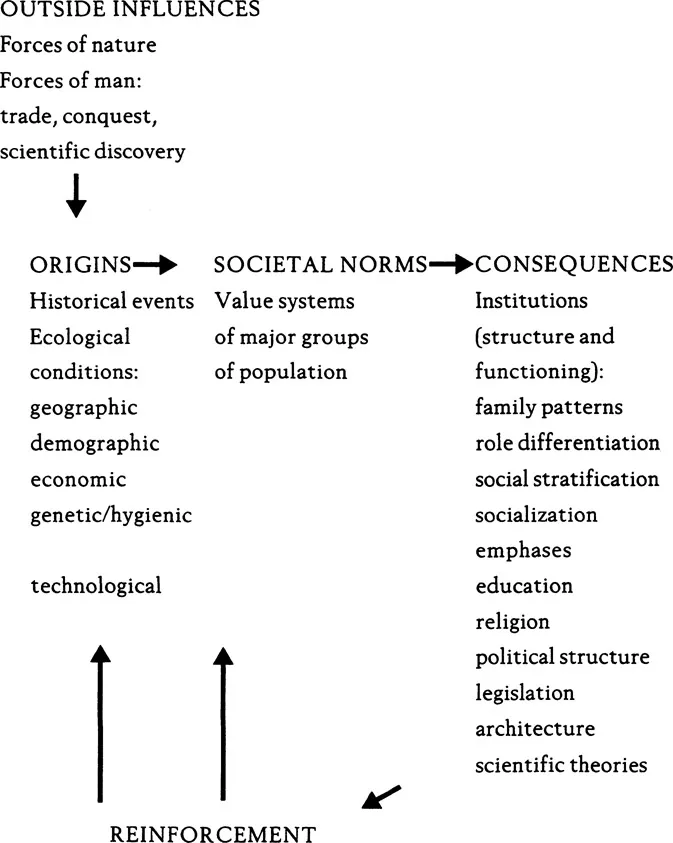

The way mental programme patterns in societies, and often in nation-states, are stabilized over generations is illustrated in Figure 1 (developed from Figure 1.4 in Hofstede, 1980:27). In the center of the diagram is a system of societal norms, consisting of the value systems shared by major groups of the population. Their origins are in historical events plus a variety of ecological conditions (in the sense of elements of the objective environment). The societal norms have led to the development and pattern maintenance of institutions in society with a particular structure and way of functioning. These include the family, education systems, politics, and legislation. These institutions, once they have become facts, reinforce the societal norms and some of the ecological conditions that led to them.

Figure 1. The Stabilizing of Culture Patterns

In a relatively closed society, such a system will hardly change at all. Institutions may be changed, but this does not necessarily affect the societal norms; and when these remain unchanged, the persistent influence of majority mental programmes patiently smoothes the new institutions until their structure and functioning is again adapted to the societal norms. Real change comes from the outside, through forces of nature (changes of climate, silting up of harbours) or forces of man (trade, conquest, colonization, scientific discovery). The arrow of outside influences is deliberately directed at the origins, not at the societal norms themselves. I believe that norms change rarely by direct adoption of outside values, but rather through a shift in ecological conditions: technological, economical, and hygienic (Kunkel, 1970:76). Such norm shifts will be gradual unless the outside influences are particularly violent (such as in the case of military conquest or deportation).

A very popular term at the present time is “national identity”. National identity is part of a national population’s mental programming, but at the conscious level of practices: symbols, heroes, and rituals. There is an increasing tendency for ethnic, linguistic and religious groups to fight for recognition of their own identity, if not for national independence. Ulster, the republics of the former Yugoslavia and parts of the former Soviet Union are evident examples. But the groups fighting are not necessarily very different in terms of their deepest level of mental programmes: values. They may fight on the basis of rather similar values, as I will show to be the case for the Flemish and Walloons in Belgium, and for the Croats and Serbs in the former Yugoslavia.

Dimensions of national cultures

In the first half of the twentieth century, social anthropology has developed the conviction that all societies, traditional or modern, faced and still face the same basic problems; only the answers differ. Attempts at identifying these common basic problems used conceptual reasoning, interpretation of field experiences, and statistical analysis of data about societies. In 1954 two Americans, the sociologist Alex Inkeles and the psychologist Daniel Levinson, published a broad survey of the English language literature on what was then still called “national character”. They suggested that the following issues qualify as common basic problems worldwide, with consequences for the functioning of societies, of groups within those societies, and of individuals within those groups:

- relation to authority

- conception of self, in particular :

- – the relationship between individual and society, and

- – the individual’s concept of masculinity and femininity

- ways of dealing with conflicts, including the control of aggression and the expression of feelings (Inkeles and Levinson, 1954: 447).

Twenty years later I was given the opportunity to study a large body of survey data about the values of people in over fifty countries around the world. These people worked in the local subsidiaries of one large multinational corporation: IBM. At first sight it may look surprising that employees of a multinational — a very special kind of people — can serve for identifying differences in national value systems. However, a crucial problem in cross-national research is always to sample respondents who are functionally equivalent. The IBM employees represented almost perfectly matched samples: they were similar in all respects except nationality which made the effects of nationality differences in their answers stand out unusually clearly.

A statistical analysis of the answers on questions about the values of similar IBM employees in different countries revealed common problems, but solutions differing from country to country, in the following areas:

- social inequality, including the relationship to authority;

- the relationship between the individual and the group;

- concepts of masculinity and femininity: the social implications of having been born as a boy or a girl;

- ways of d...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Part One Culture

- Part Two Institutions

- Biographical Notes

- Index of names

- Index of subjects