1 A Historical Sketch of the Research on Entrepreneurship

The analysis of entrepreneurship has been one of the most challenging subjects in the history of economic analysis. Research on entrepreneurship is as old as economic analysis itself. The importance of entrepreneurs in economy has always been emphasized but it has never come as far as to be develop into a consistent and comprehensive theory on entrepreneurship. Why is that? When doing research on entrepreneurship, almost every economist comes to a point where he wonders whether the entrepreneur does not fit into orthodox economic analysis or, vice versa, orthodox economic analysis is not able to explain the phenomenon of the entrepreneur. The literature on economic behavior seems to comprise of a nearly holistic approach to the understanding of humankind’s way of dealing with scarce resources. The literature on entrepreneurship, however, is eclectic and almost fails to track the quintessence of entrepreneurial behavior.

When we talk about entrepreneurship, we talk about assumptional frameworks, how to treat uncertainty, knowledge, rationality, etc.; and on top of it, we talk about methodology. This is what makes it very difficult to tell a distinct story about the entrepreneur leaving aside such kind of seemingly secondary aspects.

This part gives an overview on the work that has already been done on the topic of entrepreneurship in the economic literature and, furthermore, the attempt is made to categorize literature in order to track the development of the different strands of thought leading to different paradigms in economic analysis and thus determine the apparently symptomatic treatment of the entrepreneur.

1.1 The Pre-Neoclassics

It is not obvious at all where the actual starting point to analyze entrepreneurship is found. When we look at the literature there are various suggestions how to approach entrepreneurship.1 Casson (1990) provides a fourfold division of entrepreneurship approaches: some focus on the factor distribution of income, some investigate the entrepreneur’s role within the market process, others focus on a heroic Schumpeter vision and the fourth group analyzes the entrepreneur in the context of a firm. Nevertheless, the entrepreneur’s origin, his economic identity and his distinct economic role is still puzzling. Hébert and Link (1982) assorted various “themes” which differentiations, concerning the entrepreneur’s role, have been put forward in economic literature:

- The entrepreneur is the person who assumes the risk associated with uncertainty (e.g., Cantillon, Thünen, Mangoldt, Mill, Hawley, Knight, Mises, Cole, Shackle).

- The entrepreneur is the person who supplies financial capital (e.g., Smith, Turgot, Böhm-Bawerk, Edgeworth, Pigou, Mises).

- The entrepreneur is an innovator (e.g., Baudeau, Bentham, Thünen, Schmoller, Sombart, Weber, Schumpeter).

- The entrepreneur is a decision maker (e.g., Cantillon, Menger, Marshall, Wieser, Amasa Walker, Francis Walker, Keynes, Mises, Shackle, Cole, Schultz).

- The entrepreneur is an industrial leader (e.g., Say, Saint-Simon, Amasa Walker, Francis Walker, Marshall, Wieser, Sombart, Weber, Schumpeter).

- The entrepreneur is a manager or superintendent (e.g., Say, Mill, Marshall, Menger).

- The entrepreneur is an organizer and coordinator of economic resources (e.g., Say, Walras, Wieser, Schmoller, Sombart, Weber, Clark, Davenport, Schumpeter, Coase).

- The entrepreneur is the owner of an enterprise (e.g., Quesnay, Wieser, Pigou, Hawley).

- The entrepreneur is an employer of factors of production (e.g., Amasa Walker, Francis Walker, Wieser, Keynes).

- The entrepreneur is a contractor (e.g., Bentham).

- The entrepreneur is an arbitrageur (e.g., Cantillon, Walras, Kirzner).

- The entrepreneur is an allocator of resources among alternative uses (e.g., Cantillon, Kirzner, Schultz).2

Besides the literature explicitly focusing on entrepreneurship, the related literature is so huge that almost every subject in economic analysis is touched. So the entrepreneurial element becomes a prevailing element within the economic realm. Nevertheless, it has to be stated that the discussion, as done in orthodox theory, can also be lead without referring to the entrepreneur at all; and paradoxically, the entrepreneurial element decreases to a minor economic phenomenon not considered necessary to be taken into account.

Owing to the elusiveness of the entrepreneur within orthodox economic theory, a brief historical sketch will help to trace back the origin and the paradigmatic development of the research on entrepreneurship in order to get into the discussion. Hébert and Link (1982), Casson (1982) and Barreto (1989) among others have already given a profound overview on the literature to be investigated.

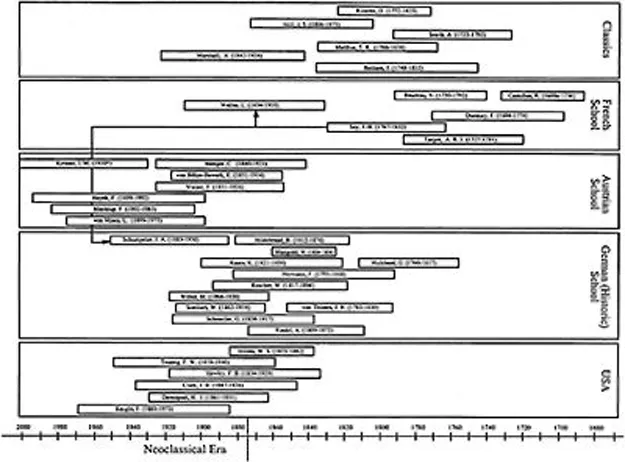

Figure 1.1 depicts a possible categorization of economists that elaborated or touched on the entrepreneur in his work.

1.2 The French School

Richard Cantillon (1680s–1734) Cantillon3 has to be seen as the precursor of the research in entrepreneurship. Cantillon was renowned as a successful entrepreneur himself (to use this term in a colloquial sense). He described economic life at his time: landowners would lease their land to farmers and live on the rent they earn. A second group, the hirelings, are employees who earn a fixed amount of money. The third group of people Cantillon calls the undertakers; they take the entrepreneurial part in economic life. The specific feature Cantillon associated with the undertaker was the fact that they face a high degree of uncertainty. Consequently, all actors who produce or buy goods at a certain price and sell them for an uncertain price, thus earning an unfixed income, belong to the group of undertakers. Cantillon emphasized that the prominent quality of those undertakers is the willingness to deal with uncertainty.4 They function as a medium to facilitate exchange and circulation. They coordinate, make decisions, engage in markets and connect producers with consumers.5

François Quesnay (1694–1774) Cantillon had a great influence on Quesnay’s work. Quesnay was actually a physician employed by Louis XV. Inspired by Cantillon’s idea of the circular flow of income, he used the analogy to the human blood circulation, which was also discovered in those days. This resulted in Quesnay’s famous Tableau Économique, an analytical model which was the first mathematical model based on the general equilibrium concept. Quesnay has also become known as the leader of the socalled Physiocrats, a group of people whose ideas were based on the metaphor of nature.6 Quesnay’s as well as Cantillon’s entrepreneurial vision was restricted to agriculture. Conclusively, Quesnay also divided economic actors into three groups adding some more specific qualities to these groups: the landowners he also called the proprietary class with property rights in land. The farmers he labeled the productive class capable to make profits and produce material for the third class, which is the artisans that manufacture goods. Quesnay was the first who brought the role of capital into the debate and pictured the entrepreneur as an independent owner of a business.7 Itisobvious that agriculture played a dominant role in economic analysis at that time so that the concept of the entrepreneur was not expanded beyond the agricultural sphere.

Figure 1.1: Economists contributing to entrepreneurship research.

Nicolas Baudeau (1730–1792) Nicolas Baudeau was one of Quesnay’s disciples. Furthermore, Cantillon’s vision of the entrepreneur as a risk bearer also influenced Baudeau’s ideas on entrepreneurship. Moreover, he contributed the idea of the entrepreneur as an innovator. He formulated the basic need of the entrepreneur to reduce his cost to increase his profits, an idea we nowadays call process innovation. Thus, he touched Schumpeter’s theory on innovation and entrepreneurship. Besides, Baudeau stressed another important aspect that had already been put forward by Quesnay, that is, the importance of the individual’s energy, knowledge and ability, which represent some of the determinants of economic success.These specific qualities provide the entrepreneur with the chance to control some aspects of the economic process whereas in terms of non-controllable aspects he puts himself at risk.8

Anne-Robert Jacques Turgot (1727–1781) Turgot’s work delivered a footing for a large field in economics. He initiated preliminary thoughts to the theory of utility, anticipating the concept of diminishing marginal utility. He generated a theory on value and money and finally a theory on capital, savings and interest which had a striking impact on his concept of the entrepreneur.9 Turgot was finance minister of Louis XVI and therefore familiar with the importance of capital in economy. According to Turgot, the accumulation of wealth goes along with the accumulation of money, which is achieved by saving. Once economic agents accumulate money they become capitalists who can make investment decisions. Then, they are in the position to decide whether to buy land, to invest in a business or simply lend the capital to others. Consequently, Turgot’s entrepreneur in the first place is a capitalist and may opt to either become a landowner, simply stay a capitalist as a pure lender, or become an entrepreneur. In Turgot’s concept of the entrepreneur, the significance of capital dominates the entrepreneurial role. The entrepreneur is a capitalist-entrepreneur who seeks to earn interest on the capital invested and to obtain remuneration for his manpower.10

Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832) Jean-Baptiste Say accomplished a big step forward in two fields: not only did he deliver he the building blocks for economic theorizing still to come at that time, he also managed to in-tegrate the entrepreneur into a complete system.11 Concerning entrepreneurship, he was the first to solidify the entrepreneur as an independent economic agent who combines and coordinates productive factors. Thus, Say emphasized the functional role of the entrepreneur as a coordinator, as the active role within the economic process, which makes the entrepreneur unequivocally distinguishable from the capitalist, the landowner and the workman.12 At the same time, Say’s economic concept constitutes a pivotal point in economic analy...