1 The myth of free-trade Britain and fortress FranceTariffs and trade in the nineteenth century1

John Vincent Nye2

“Our Parliament is to be prorogued on Tuesday and dissolved the same day,” Victoria wrote to her Belgian uncle on June 29. 1852. “Lord Derby himself told us. that he considered Protection as quite gone. It is a pity they did not find this out a little sooner; it would have saved so much annoyance, so much difficulty.”3

While France [1815–1848] was thus maintaining almost intact her virtually prohibitive tariff, England was making rapid progress toward the adoption of complete free trade, so that the divergence in the tariff policies of the two countries became steadily greater.4

One of the great economic advances of the nineteenth century was the spread of liberalism and the expansion of world trade. In the popular fable that makes “history” of this event, Britain was the great nation of free trade, whose liberal commercial policy made possible the achievement of unparalleled peace and prosperity. Britain’s abandonment of protection and subsequent rapid success spurred other nations to follow her example, culminating in the general adoption of more liberal trade policies in neighboring European states.

The view that the rise of free trade in Britain initiated the rise of free trade in Europe still frames our historical explanations of the economic expansion of the last century.5 The conventional wisdom is that France – in contrast to Great Britain – had an outmoded and crippling system of tariffs and prohibitions in the first half of the nineteenth century, and that it was not until the 1860 Anglo-French Treaty of Commerce that the French took steps toward moderate protection.

But how do we know this to be true? From what evidence have we concluded that Britain was the solitary free trader in the early-to-mid-nineteenth century? What criteria have been used to establish that Britain vigorously liberalized while other nations – especially France – continued to close their doors and raise obstacles to the importation of other nations’ products? Paul Bairoch wrote the following on the period in the latest volume of The Cambridge Economic History of Europe:

The situation as regards trade policy in the various European states in 1815–20 can be described as that of an ocean of protectionism surrounding a few liberal islands. The three decades between 1815 and 1846 were essentially marked by the movement towards economic liberalism in Great Britain. This remained a very limited form of liberalism until the 1840s. and thus only became effective when this country had nearly a century of industrial development behind it and was some 40–60 years ahead of its neighbors. A few small countries, notably The Netherlands, also showed tendencies towards liberalism. But the rest of Europe developed a system of defensive, protectionist policies, directed especially against British manufactured goods.6

Similar stories are told elsewhere in the literature.7

But an examination of British and French commercial statistics suggests that the conventional wisdom is simply wrong. There is little evidence that Britain’s trade was substantially more open than that of France. Very little of the existing work on British or French trade has taken a comparative perspective, and there has been little economic, as opposed to political, analysis of the commercial interaction between nations. Most of the economic work has focused on the volume of trade in the two nations and has taken the changing tariffs for granted as an interesting stylized fact.

When the comparison is made, the trade figures suggest that France’s trade regime was more liberal than that of Great Britain throughout most of the nineteenth century, even in the period from 1840 to 1860. This is when France was said to have been struggling against her legacy of protection while Britain had already made the decision to move unilaterally to freer trade. Although some have recognized that Napoleon III had begun to liberalize France’s trade regime even before the 1860 treaty of commerce, both current and contemporaneous accounts treat the period before the 1860s as a protectionist one in France and a relatively free one in Britain.

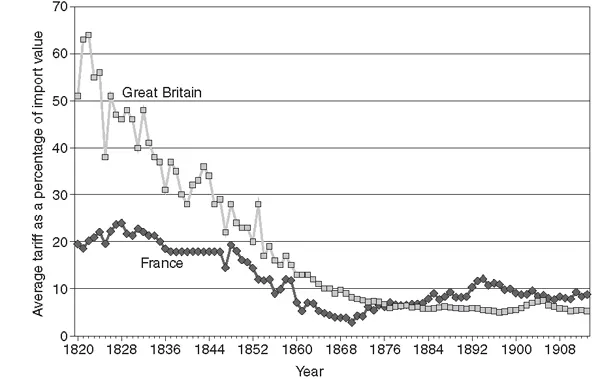

A straightforward examination of the raw numbers immediately alerts that something is amiss in the fable. Table 1.1 and Figure 1.1 present the average customs rates of the United Kingdom and France, where the rates are calculated from tariff revenues as percentages of the value of importa-bles. These numbers are taken from Albert Imlah’s reworking of British trade statistics and Maurice Lévy-Leboyer and François Bourguignon’s recent work on nineteenth-century France. The figures show French tariff rates to be substantially lower than British rates for the period of “high protection” during the first four decades of the century. Average French tariffs in this earlier period were comparable to those of Britain after she had begun her move to free trade with the abolition of the Corn Laws. Judging by the absolute size of the fall in average tariff levels, England seems to have shown a much greater change in tariff levels than France.8 But Britain started out from much higher levels – over 50 percent – than did France, which never exceeded 25 percent in any single year. Bearing in mind the high point from which British tariff levels fell, one notes that the changes in tariffs seemed to fit the conventional chronology, beginning in the late 1820s and falling rapidly from the 1840s onward.9 Similarly, French tariffs steadily declined until the early 1850s and then plummeted to a low of around 3 percent in 1870 – well below the minimum for Britain at any time in the nineteenth century. French tariff levels remained at quite low levels, until the move back toward protection in the last ten or fifteen years of the century. British average tariff levels did not compare favorably with those of France until the 1880s, and were not substantially lower for much of the time. The view of Britain as the principled free trader is most consistent with the tariff averages from the end of the nineteenth century, indicating Britain’s commitment to keeping tariffs low in opposition to rising protectionist sentiment both at home and abroad. Furthermore, her movements toward free trade were magnified by the scale of her involvement in the world economy. In fact, Britain’s rapid shift to freer trade was fully matched in timing and extent – and even anticipated (in the French discussions of tariff rationalization before 1830) – by the commercial restructuring taking place in France.

Table 1.1 Average customs rates of Great Britain and France: net customs revenue as a percentage of net import values (quinquennial averages of annual rates), 1821–1914

Figure 1.1 Average tariff rates: tariff revenue as a fraction of all imports.

Calculations of average tariff rates based on the ratio of total tariff revenues to total importables require some qualification. For instance, the tariff level may be set so high that certain items that might otherwise be imported in large amounts enter fitfully or not at all.10 In the case of outright prohibitions, consumers are implicitly paying a tariff equal to the difference (at most) between the home price of the domestically produced good and its foreign equivalent. Adjustments need to be made to get more comparable British and French tariff statistics.

In short, we have a classic index-number problem, complicated by the lack of a unique and well-accepted index of the degree of openness of a nation’s trade. If one nation had had lower tariffs on every single item of trade than the other, it would be easy to state categorically it had the more liberal trading structure.11 The inequality is not so simple, of course. Yet we do not need precise average tariff rates to see that British tariffs were not uniformly or even “generally” below those of France for most of the century.

Even without making adjustments, we can see that certain parts of the argument are robust to these re-specifications. First, one would expect the following to be true: if items that were prohibited prior to the policy changes in the late 1850s and 1860s were then permitted to enter at some positive tariff, it might well be the case that the average tariff levels after prohibitions were removed would increase, given the new import composition. For instance, most cotton textiles, which were banned prior to the 1860 treaty, were imported in fairly large quantities after the treaty at a tariff rate (20 to 30 percent) higher than the overall average. But if this meant that average tariff levels prior to the Second Empire would need to be adjusted to take this prohibition into account, the size of the drop in average tariff levels during the period from 1852 to 1870 is underestimated by the unadjusted average tariff rates, because earlier all-commodity averages would be too low. Given the already low tariff levels of the 1860s, full information about the appropriate corrections would only serve to underline the openness of Napoleon Ill’s France and the magnitude of the change in tariffs from the early 1840s to the end of the Second Empire.

A substantial share of French imports was duty free and, though prohibitions may have distorted this figure in the first half of the nineteenth century, the proportion of duty-free items did not change much and even grew in the period when prohibitions were replaced with tariffs.12 This runs counter to the intuition that the existence of prohibitions masked the true extent of protection by biasing the fraction of duty-free imports upward relative to the years of freer trade. Table 1.2 shows that the proportion of French imports by value that were duty free stood at around 61 percent in 1849 and increased to 65 percent by 1869. What is remarkable is the stability of the shares of dutiable, and duty-free items in value terms through periods of widely varying tariff levels and trade restrictions. Thus, with only a third of all imports being dutiable even in the period when moderate tariffs replaced all prohibitions, it should come as no surprise that even fairly large adjustments in the composition of earlier imports would not do much...