![]() Part I

Part I

The state and the political system![]()

1

New wine in old bottles: political parties under Mohammed VI

James N. Sater

You will always find me, my dear and loyal people, at the frontline, at the head of those who are determined to thwart every discourse that aims at casting doubt on the importance of holding elections and on the utility itself of political parties. I will foil all those trendy practices that aim at posing a threat to their credibility. The political maturity that we have achieved requires from us the duty to outlaw faulty, nihilist, and deceptive conceptions, which attack the respect owed to the democratic verdict of the ballot boxes.

King Mohammed VI, July 30, 2007

Political developments in Morocco follow patterns that are sometimes surprisingly familiar to the attentive observer. Euphoria over free and fair elections, democratic rhetoric, and real opposition to governmental authority have been as common as election rigging, party manipulation, and severe restrictions on the freedom of speech. What holds true for the political system as a whole also applies to the multi-party framework. Parties that appeared to be in opposition to royal rule in one year formed governments under royal authority in another. Similarly, the monarchy created parties that were explicitly loyal to the king, only to ensure that other parties acquiesced to their junior status in the distribution of power. As a consequence, party politics apparently reflect intra-elite struggles. The rhetoric associated with socialism, democracy, or liberalism appears as a facade in a political game where everything has been decided in advance and nobody seriously contests the outcomes. What remains contested are only the individual positions that certain secondary players are able to obtain.

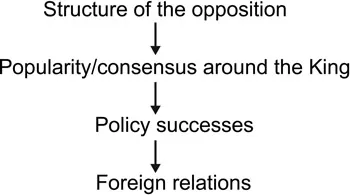

The regime’s objective may not be the establishment of a system of checks and balances, nor is the monarchy’s authority seriously questioned by any of the contestants. Nevertheless, Morocco’s multi-party system performs a number of very important secondary functions, one of which is to create a political sphere in which, at least in theory, contestation can be expressed.1 It has been this potential for contestation and resulting appearance of political liberalism that has been one important source of legitimacy for Morocco’s three post-colonial kings.2 Within this context, the analytical concepts of strength and weakness of Morocco’s political regime provide an interesting perspective. Depending on its own relative strength, the regime has allowed criticism to develop. When it gained strength, it then increasingly believed that it could clamp down on political opposition. Conversely, at times of relative weakness, the regime acted to reinforce the political consensus by integrating political parties, as long as they were not strong enough to challenge royal authority, otherwise the regime would lose too much by engaging in necessary compromises.3 The result was the creation of a zone of political liberalism in which the regime is neither too weak nor too strong in relation to other political contenders, establishing a balance between political liberalism “granted” by the monarch, and the submission to authoritarian rule by political parties. This dynamic can be expressed in the following model:

Figure 1.1 Zone of political liberalism

However, a balance between the appearance of political liberalism and submission to royal authority has not always been easy to achieve, and the primary objective of royal interventions in party politics has been to ensure that no serious challenges would arise. From this observation comes the primary reason for analyzing political parties in Morocco’s political system. Depending on particular contexts, royal interventions are indications about whether the regime feels either strong or weak. Similarly, the state may feel at times that it has to compromise with actors or, alternatively, that it is able to overlook the ambitions and ideas of potential rivals as expressed in political parties. An analysis of the party system thus gives the observer an important way of assessing the stability and direction of the political system as a whole. In the second half of Mohammed VI’s first decade in power, the previous trend towards power sharing and political liberalization ground to a halt, and Morocco entered a period of increasingly open conflicts and tensions. In contrast to the regime consolidation period of the first half of Mohammed VI’s reign (1999–2005), the state, at least until the outbreak of the Arab Spring protests in early 2011, felt increasingly strong with regards to regime legitimacy and the public’s support of the monarch. Although these tensions and conflicts were addressed at the state level by strategies similar to those used in the past, contemporary issues of contention were fundamentally different in structure and content than previous ones. They shifted from a debate about the distribution of power to a debate about moral values in a rapidly changing society. This means that old bottles were filled with new wine: the appearance of similar state strategies of dealing with political parties masked the changing content of political tensions. It remained to be seen whether or not the Palace’s constitutional reform measures in mid-2011, taken in response to the region-wide popular protests which began to rear their head in Morocco, would be a harbinger for change in the realm of state-party dynamics.

The development of the party system and the articulation of political tensions under Hassan II

In the post-independence period, Morocco’s party system developed amidst tensions that concerned the distribution of power. The claims of the monarchy to absolute rule were countered by the conservative Arab-Islamic Istiqlal party’s own claims to single party status and, more timidly, to rule. The Istiqlal’s claims were partly based on the fact that it had been the leading force in the successful struggle for independence and the return of Sultan Mohammed V to Morocco from French-imposed exile. Due to strong intra-elite rivalries that accompanied colonial rule, the monarch could fairly easily capitalize on political divisions and splits. These existed primarily between rural and urban, and leftist and Islamic-conservative elites, respectively, with divisions compounded by regional and tribal identities. These splits led to the three main post-independence political currents of the Popular Movement (rural, conservative and tribal), Istiqlal [Independence] (urban; conservative), and the National Union of Popular Forces (UNFP) (urban; leftist). A divide and rule policy was facilitated by the monarch’s religious, historical and tribal credentials as well as access to the French colonial security regime. All of this commanded more loyalty than any of the credentials that contending parties possessed. The result was a mixture of political oppression, a divided and partially co-opted opposition, and political parties in which rural notables secured their own self-interest by expressing their loyalty to the king alone. A large number of ‘independents’ with no party affiliation further competed for positions of authority in the administration, which further fragmented the political landscape. The officer corps and ministry of interior officials, often recruited from Amazigh (Berber) tribes, took a leading position in the distribution of power and resources, especially after the dissolution of parliament in 1965.4

From this brief description it appears that tensions developed in an attempt to fill the power vacuum that the French had left behind, filled with social and personal interests that were often only superficially expressed in political ideologies. Clearly though, the main questions over what type of Morocco its political forces wanted to construct made social tensions intrinsic to the state-and nation-building process in this post-independence period: The role of Islam and the place of individual rights were disputed among contenders, those who were either fighting for an increase in their rights, or those who feared a loss of their privileges.5 The socialist leanings of Mehdi Ben Barka were as much related to his own modest family background – he was Crown Prince Hassan’s mathematics tutor – as Allal El Fassi’s conservative Arab-Islamic ideology was related to the prestige and wealth with which his Sharifian background endowed him. In addition, as the stakes seemed very high in the beginning of this process of state-building, many actors did not hesitate to use an extensive amount of violence in order to achieve their objectives. Political assassinations and disappearances, rural revolts against the Istiqlal party, and military crackdown operations were used by many of the actors involved. This resulted in fierce tensions that almost led to the disappearance of the monarchy in two military coup attempts in 1971 and 1972.6 It can safely be said that after these traumatic experiences, which resulted in the palace’s achievement of unchallenged hegemony, the tensions within the political party system eased significantly. Core left-wing political parties such as the newly-founded Union socialiste des forces populaires (USFP; 1973) and the Parti du progrès et du socialisme (PPS; 1974), as well as the nationalist Istiqlal, explicitly accepted royal authority and the king’s religious position as Amir al-Mu’minin. This came after a new wave of patriotic nationalism and political co-optation was unleashed by the monarchy’s Western Sahara campaign, beginning in 1975. After the general elections of 1977 that strengthened the pro-monarchy political groupings, the monarch invited some of them to form a government, establishing a pattern of pseudo-democratic, apparently “modern” governance that has continued up until today.7

Core characteristics of Morocco’s party system

After these events, the party system developed some core features that were inherited by Mohammed VI upon his accession to the throne in July 1999. First, the main goal of political parties’ activities became power sharing, not democratic rule, even if the rhetoric of constitutionalism made this difference sometimes confusing. During the constitutional reform process of the 1990s (two new constitutions were drawn up and passed by referendum in 1992 and 1996, respectively), the four parties that formed the so-called “democratic bloc” (al-koutla al-dimuqratiyya) – the left-of-center USFP, the conservative-nationalist Istiqlal, the ex-communist PPS, and the small leftist Organisation de l’Action Démocratique et populaire (OADP) increasingly asked for a “pact,” a mode of election that would put them into government responsibility irrespective of electoral results. In spite of their 1993 electoral defeat, they believed themselves to be the only credible “democratic” force in Moroccan politics that the king should quite simply acknowledge.8 Second, throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the monarchy increased its direct involvement in party politics and resorted to the creation of new parties that would draw voters away from other parties through the kingdom’s well-established patronage system. The king could thereby counter any potential grumbling regarding his policies not through coercion alone, but also through “democratic” means. Hence, the leader of the USFP, Abderrahman Bouabid, was first sentenced to six months imprisonment in 1981 when he criticized Hassan II’s plan to organize a referendum on self-determination in the Western Sahara. The follow-up came in 1984, when the Constitutional Union (UC) party won the largest percentage of votes in the general elections after having been founded only a couple of weeks earlier, resulting in the removal of Bouabid’s USFP (and the Istiqlal) from government. They would remain in opposition until 1997–98. Already in 1979, the king had created the National Movement of Independents (RNI), headed by his son-in-law Ahmed Osman. Third, since the late 1970s, political Islam has become a major pre-occupation. Its widespread popularity was evidenced by movements such as al-Adl wal-Ihsan (“Justice and Spirituality”) that drew its force from the country’s Sufi cultural and organizational roots (zawiya and tariqa), and the economic deprivation, especially prevalent in the large urban centers of Casablanca, Salé and Tangier. The pace of rural exodus was such that by the early 1990s, more than 50 percent of the Moroccan population lived in the cities, up from about 20 percent at the time of independence. This posed a threat to the religious and economic elites, including monarchical and political forces, and thus brought together the former contenders for power desiri...