eBook - ePub

Agricultural Transformation in a Global History Perspective

- 342 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Agricultural Transformation in a Global History Perspective

About this book

History teaches us that agricultural growth and development is necessary for achieving overall better living conditions in all societies. Although this process may seem homogenous when looked at from the outside, it is full of diversity within. This book captures this diversity by presenting eleven independent case studies ranging over time and space. By comparing outcomes, attempts are made to draw general conclusion and lessons about the agricultural transformation process.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Agricultural Transformation in a Global History Perspective by Ellen Hillbom,Patrick Svensson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Agricultural transformation, land ownership, and markets in inland Spain

The case of southern Navarre, 1600–1935

Introduction

Causality in the process of long-term economic growth is probably the major concern of economic history. At times, this causality is observed in positive terms, seeking factors that favoured growth in advanced nations. This has been addressed recently from various perspectives in books such as Clark (2007), De Vries (2008), Mokyr (2009), Allen (2009), and McCloskey (2010). At other times causation is seen in negative terms, trying to identify the obstacles that condemned certain countries to economic backwardness. The process of globalisation and the need to build a truly global historical narrative has recently accorded growing importance to attempts to provide a unified interpretation of both aspects (Austin 2008b). The explanatory models proposed are varied. Engerman and Sokoloff (1997) suggest that differences in the geographical and factor endowments favoured different structures (family farms in one case and large plantations in another), which could explain differences in the development process. The argument has been taken further by Easterly (2007), with greater emphasis on the influence of relative factor endowments in agriculture, on social inequality and its effects on development potential. Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (2001, 2002) have argued that the geographical features, including the impact of disease on European settlers and resource endowments, favoured different types of institutions (extension of property rights or rent extraction) that led to divergent results. Other authors have placed greater emphasis on institutions and transaction costs as determinant, in line with the argument put forward by North and Thomas (1978) and North (1984, 1993, 2005). Thus, La Porta, López-de-Silanes and Schleifer (2008) used distinctions between the traditions of Common Law and Civil Law to explain the different performance of the economies under British influence over the others.

In this scenario, the Spanish case is particularly interesting. At first glance it appears to perfectly fit the ‘reversal of fortune’ thesis (Acemoglu et al. 2002). After a period of splendour during the sixteenth century, Spain fell behind in economic development, and entered the twentieth century far behind the rest of Western Europe. However, between 1760 and 1860 Spain saw several major institutional changes that consolidated new property rights and facilitated the integration of markets (Artola 1973; García-Sanz 1985). These institutional changes were to a large extent directed at agriculture, since this was the main sector of pre-industrial Spain (as it was in all pre-industrial economies). The factor that showed the most profound change was land, but labour and capital markets were also transformed. First, the nature of property rights was changed. The ‘Acotamientos’ Act of June 8, 1813, restored in 1836, gave full freedom to landowners to fence in and cultivate their fields. Second, it caused a massive transfer of property through ‘Desamortización’ laws (1798, 1836, 1841, 1855), which put up for auction the Church and municipal lands, and the law of ‘Desvinculación’, which liberalised the property of the nobility. Third, replacing the cumbersome feudal taxation with multiple recipients (Church, lords, Crown) to create a unified land tax by the government. Fourth, labour markets were also liberalised, and freedom to negotiate the price of labour was enacted in 1768 (1817 in Navarre). Finally, credit markets were also affected by the disentailment laws, auctioned or amortised loan credit in the ecclesiastical entities listed as creditors. At the same time, a form of short-term mortgage (obligatión), hitherto used by traders, spread in agriculture, replacing traditional long-term credits (censal). The changes were, therefore, of great importance, and established an institutional framework with strong property rights and freedom of contract.

This should have promoted rapid and intense economic growth, as envisaged by the promoters of these laws. And yet, compared to what happened in other European countries, the development process was both limited and late. Why did institutional change not bring, in the short term, the truly significant economic change that would have led to industrialisation? Spanish intellectuals have been trying to solve this puzzle for over 100 years. Authors such as Joaquín Costa in the late nineteenth century (in a bleak intellectual climate caused by a military defeat by the US and the loss of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines) said that institutional changes were merely superficial and that the social and political structures remained dominated by an oligarchy that was responsible for distorting the political game (Costa 1982). Between 1970 and 1986, in a context characterised by the agony of the Franco dictatorship and entry into the European Economic Community, which ended decades of Spanish exception, the new Spanish historians stressed the limits of institutional change as a result of the tacit agreement between aristocracy and bourgeoisie (Fontana 1975; Nadal and Tortella 1974). In more recent times, explanations have been sought in other fields such as environmental constraints when adopting the technological model of northwestern Europe (Garrabou 1990; Pujol et al. 2001) or the poor design of contract structures in rural Spain (Carmona and Simpson 2003).

So, despite a series of profound political and institutional changes during the first half of the nineteenth century, the country did not complete its industrialisation process, remaining as a laggard in the European context. From an institutional point of view, it is possible to argue that the result was predictable, given that Spain fitted the French model of Civil Law, which is less flexible than Anglo-Saxon Common Law for promoting industrial capitalism (La Porta et al. 2008). But why were such large differences detected between regions governed by identical legal systems? This question makes it necessary to carefully examine other parameters. The literature provides several options, from geography (Engerman and Sokoloff 1997) and factor endowments (Austin 2008a) to agrarian class structure (Brenner 1988), social inequality (Easterly 2007), or human capital formation (Mokyr 2009).

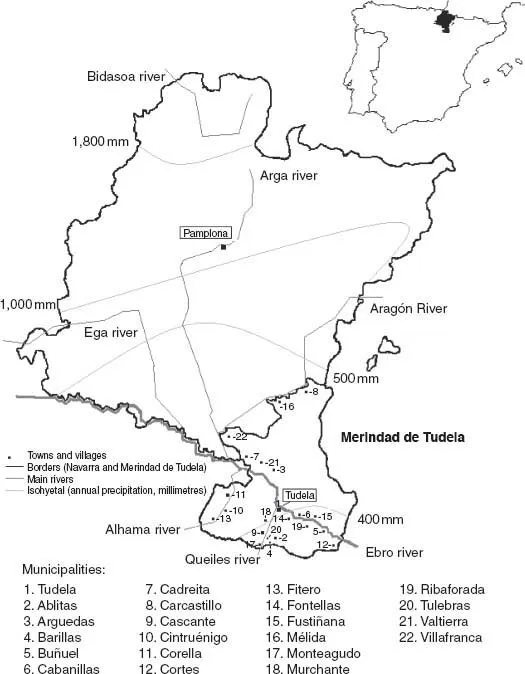

The aim of this chapter is to answer three questions. Was the performance of Spanish agriculture really so poor in the nineteenth century? What effect did the institutional changes have on the potential for agricultural development? And what forces hindered further development? To offer an interpretation that takes into account the complexity of historical processes, this chapter uses as its unit of analysis a small geographical area: the Merindad de Tudela (see Figure 1.1), situated in the middle Ebro Valley, extending over 1,502 km2.

We will first measure and contextualise the agricultural growth in this area in the nineteenth century. Second, we will detail the initial conditions through agro-climatic characterisation and an analysis of a rich cadastral source dating from the early seventeenth century. In the third section, we will describe the major changes experienced by the agricultural economy and rural society in the long term. Finally, we will question the factors that could limit growth after a process of institutional change, such as that described in this chapter.

Slow agricultural growth and changes in output composition

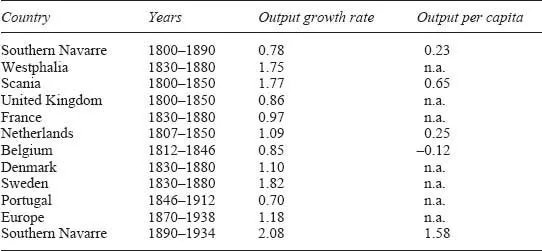

To begin with, we will try to put agricultural growth in southern Navarre in a broader context. Table 1.1 shows some estimated growth rates in European agriculture (Olsson and Svensson 2010; Kopsidis and Hockmann 2010). The figures estimated for southern Navarre only include gross agricultural product for the period 1800–1890. Livestock production figures are of poor quality, and we have to settle for an approximation. The main idea derived from Table 1.1 is that agricultural growth in this region was less than in other parts of Western Europe during the nineteenth century. The huge distance from the central and northern regions of Europe, whose growth exceeded 1.7 per cent annually, is particularly remarkable, as can be seen from Scania and Westphalia, which were studied by the authors cited. However, the rate of 0.78 per cent for gross agricultural output between 1800 and 1890 is not insignificant. This rate rose to 2.08 per cent between 1890 and 1934, above the rate estimated by Federico (2005: 18) for the whole of Europe.2

Table 1.1 Annual agricultural growth in Europe (constant prices)

Sources: Kopsidis and Hockmann (2010: 210); Olsson and Svensson (2010: 287); Andrade Martins (2005: 221); Federico (2005: 18); Table 1.3 for Navarre.

Figure 1.1 Map of Navarre and southern Navarre (Merindad de Tudela) (source: author’s elaboration from Gran Atlas de Navarra (1986)).

Table 1.2 identifies the crops that boosted agricultural growth in Merindad de Tudela during the nineteenth century and the first third of the twentieth century.3 In the earlier period, two traditional Mediterranean crops were primary, vineyards and olive groves, and two crops of American origin, potatoes and maize. The production of wheat and pulses grew modestly, while other traditional crops (hemp, rye, barley, and oats) decreased to a greater or lesser extent. Between 1890 and 1935 the most dynamic crops were wheat and cereals, and particularly a new crop, sugar beets, which was promoted by the sugar production companies in the region, after the independence of Cuba. These changes reflected the transformations undergone in national and international contexts. When the international market for wine and oil became saturated in the late nineteenth century (Pinilla 2002), the regional production model was forced to seek a new specialisation in the supply of food (wheat, sugar) to the internal market (Gallego 1986). Spanish domestic demand and the extraordinary circumstances of the First World War constituted powerful stimuli for growth in this period.

In short, there was undeniable agricultural growth, with different patterns of specialisation in response to changes in product and factor markets. These changes were based on the ecological conditions offered by the territory and the available technology of the time (viticulture and olive growing in the nineteenth century, and dry farming and agribusiness in the early decades of the twentieth century). But what was the role of geography and institutions in this process of growth, and what were their limits?

Environment, habitat, and landholding in southern Navarre

The growth potential of this region would seem to have been very large, judging by the low population densities that existed in the mid-sixteenth century. The population count in 1553 showed 3.23 households per square kilometre, which can be translated to around 12–15 inhabitants/km2 (in line with the Spanish average). However, this level was not exceeded until the second half of the eighteenth century, leaving this area sparsely populated (Figure 1.2). The main obstacle to denser settlement was the climate, which imposed significant restrictions on the crops and the landscape. Rainfall is low, less than 500 mm per year, down from 400 mm in the southeast. The monthly rainfall maximum occurs in the spring, with records of between 40 and 52 mm. By contrast, the level in July and August does not exceed 25 mm. Average annual temperatures are around 13.5 °C, with a minimum monthly average in January (5.4 °C) and a maximum in July of 22.8 °C. However, the daytime temperature reaches 26.6 °C in this latter month, and the mean absolute maximum goes up to 37.7 °C. Winter is relatively mild, with average minimum temperatures in January of –5 °C, and just 44 days with any risk of frost between November and March. The intense evaporation caused by a thermal regime with high summer temperatures and strong drying effects caused by the wind from the northwest (cierzo) (a Foëhn effect), leads to a long, pronounced summer drought that may last four or five months. The aridity index (calculated according to De-Martonne) for the whole year stands at 17.7, and it drops to under ten in the summer months. The index portrays a semi-arid climate that could be ascribed, according to the classification of Papadakis, to a dry Mediterranean regime. The Turc index of agricultural potential for dry lands is below ten. Under these extreme conditions, the rivers (Ebro, Aragón, Alhama, and Queiles), and the canals derived from them, made a stable agriculture possible, rai...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Agricultural transformation, land ownership, and markets in inland Spain: The case of southern Navarre, 1600–1935

- 2 Are institutions the whole story? Frontier expansion, land quality and ownership rights in the River Plate, 1850–1920

- 3 State-led agricultural development and change in Yogyakarta, 1973–1996

- 4 Russian peasants and politicians: The political economy of local agricultural support in Nizhnii Novgorod province, 1864–1914

- 5 Slaves as capital investment in the Dutch Cape Colony, 1652–1795

- 6 Land inequality and agrarian per capita incomes in Guadalajara, Spain, 1690–1800

- 7 Smallholders’ access to financial institutions in Meru, Tanzania, 1995–2011

- 8 Production and credits: A micro level analysis of the agrarian economy in Västra Karaby parish, Sweden, 1786–1846

- 9 Land concentration, institutional control and African agency: Growth and stagnation of European tobacco farming in Shire Highlands, c.1900–1940

- 10 Peasants households’ access to land and income diversification, the Peruvian Andean case, 1998–2000

- 11 Institutional models for accelerating agricultural commercialization: Evidence from post-independence Zambia, 1965–2012

- Reflections on the role of agriculture in the structural transformation: A macro–micro perspective

- Index