- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Poverty in Transition Economies

About this book

This study addresses the experience of, and responses to poverty in a range of transition economies including Russia, Ukraine, Hungary, Slovenia, Uzbekistan, Romania, Albania and Macedonia. It covers topics such as the definition of poverty lines and the measurement of poverty; the role of income-in-kind in supporting families; homelessness and destitution; housing; the design, targeting and administration of welfare; and personal responses to economic transition.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Poverty in Transition Economies by Sandra Hutton,Gerry Redmond in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1Poverty in transition economies

An introduction to the issues

Introduction

In their book on income distribution in Central and Eastern Europe before the fall of the Iron Curtain, Atkinson and Micklewright (1992) wrote:

It is everyone's hope that the present economic and political reforms in Eastern Europe will lead to marked rises in the national incomes of these countries, narrowing the gap between their standard of living and that found in Western Europe. At the same time, it seems clear that the reforms will do much more than change average income in the countries concerned – they will also change its distribution.

(Atkinson and Micklewright, 1992, p.1)

They argued that at the time there was remarkably little interest in the distribution of incomes and related issues in economies in transition. Their book aimed to set a benchmark against which the impact of transition on inequality and poverty could be judged.

However, when their book was published in 1992, there was still considerable optimism that the duration of transition would be short, and that its economic benefits would, relatively quickly, be enjoyed by the majority. Events since 1992 have suggested otherwise. Most transition countries have endured ten years of economic contraction or stagnation and real incomes have declined. While some countries have so far survived economic transition in reasonably good shape, for others the consequences of economic transition have been disastrous.

The contributions to this volume comprise fifteen analyses of different aspects of poverty and responses to poverty in countries undergoing economic transition in Central Europe, the former Soviet Union and the Balkans. The authors of these analyses come from a variety of backgrounds, including academia, the public service and international organisations. Most chapters are authored or co-authored by people who are from the countries described. In several chapters these authors offer valuable insights into the measurement and experience of poverty, and the responses to poverty in transition economies.

In this introductory chapter, we examine briefly two important legacies of Communism which have emerged over a decade of research into poverty in transition economies: first, the macroeconomic environment and its relationship to poverty; and second, some important institutional features of the Communist system. We discuss the chapters in this book in two groups: the first covers countries experiencing relatively severe poverty in transition. The second group includes the more ‘advanced’ economies in transition. These two groupings are discussed briefly in the third and fourth sections. The last section provides a concluding note.

The Communist legacy

The macroeconomic environment and its relation to poverty

While it was accepted in 1989 that the start of economic transition in former Communist countries heralded a new and very uncertain era, there is no doubting the optimism with which the future was embraced. For example, in 1990 the World Bank suggested that although there was considerable uncertainty surrounding the outlook for Eastern Europe, by the end of the decade growth would be robust, and overall per capita income would grow by about 1.5 per cent per year over the period (World Bank, 1990, p.18). In the case of the more developed economies of Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, Gelb and Gray (1991) were more specific, forecasting that economic decline associated with transition in these countries would bottom out in 1992, and steady growth would ensue, leaving these countries 20 per cent better off in 2000 than they had been at the start of transition.

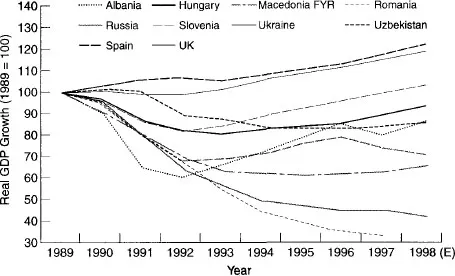

Events have shown that such forecasts were wildly optimistic. Between 1989 and 1992, the gross domestic product (GDP) of nearly all transition economies shrank dramatically, as Figure 1.1 shows. For example, it decreased by 40 per cent in Albania, 30 per cent in Macedonia and by about 18 per cent in Hungary and Slovenia. Figure 1.1 also shows that after 1992, the position of Hungary and Slovenia began to improve gradually, but the position of others continued to worsen. In Uzbekistan, a gentle decline in GDP continued until 1996. In Romania and Albania, real GDP grew between 1993 and 1996, but began to decline again in 1997. For Ukraine and Russia, the two largest European countries undergoing economic transition, the picture is more severe. In both countries there has been a constant and steep decline in real GDP: in 1997 it was estimated to be 46 per cent of its 1989 value in the case of Russia, and 34 per cent of its 1989 value in the case of Ukraine. Of all the transition economies in Figure 1.1, only Slovenia was (slightly) better off in 1998 than it had been in 1989.

The positive performance of the two Western countries in Figure 1.1 over the same period makes the relative performance of the transition economies seem worse. Both Spain and the UK grew by about 20 per cent in real terms over the 1990s. Indeed, most Western economies grew through the 1990s (OECD, 1998). Transition economies therefore not only became poorer in real terms as they restructured; the gap in wealth between them and Western economies widened.

Figure 1.1 Real GDP growth in selected transition economies, 1992–2000.

Source: OECD (1993–8), except Albania (World Bank, 1998); Macedonia FYR (World Bank, 1995; IMF, 1998); Uzbekistan (Falkingham, 1998). Some data for 1989 and 1990 are also taken from the TransMONEE 3.0 Database of UNICEF-ICDC.

As Table 1.1 shows, not only was there variation in the extent to which different transition economies shrank during the 1990s, but there were also clear differences in terms of average income (measured here according to the US dollar equivalent of per capita gross national product (GNP)). Of the countries in Table 1.1, Albania was by far the poorest in 1994, with a per capita GNP of $380, followed by its neighbour, Macedonia, with $820, and then Uzbekistan, Romania, Ukraine and Russia. Slovenia is by far the richest of the transition countries listed in Table 1.1, with a per capita GNP of $7,040, almost twice that of the next richest transition country, Hungary. However, per capita GNP in Slovenia is only just over half that in Spain, and less than 40 per cent that in the UK. The translation of per capita GNP into purchasing power parities (PPPs) equalises the countries somewhat: expressed in PPPs, Uzbekistan's per capita GNP is 90 per cent of that in the Ukraine, and Hungary's GNP is almost equal to the Slovenian figure. However, these latter countries are still the wealthiest of the transition economies, and the difference between all the transition countries and the Western countries remains considerable.

Not surprisingly, those countries with the lowest income figures also have the highest poverty figures. Using an absolute poverty line of US$4 per day, Milanovic (1997) shows that while poverty in the Central European countries of Hungary and Slovenia was low in the mid-1990s, it was very high in Romania and the countries of the former Soviet Union. In Romania, Russia, Ukraine and Uzbekistan, half or more of the populations were estimated to be in poverty according to the US$4 standard in 1993–95.

Table 1.1 Estimated average income and poverty headcounts in selected transition countries, Household Budget Survey data

| GNP per capita | PPP estimates of | Poverty headcount | |

| (US$ per year) | GNP per capita | (per cent of population) | |

| 1994a | (US$ per year) | 1993–95c | |

| 1994b | |||

| Albania | 380 | – | – |

| Hungary | 3,840 | 6,080 | 4 |

| Macedonia FYR | 820 | – | – |

| Romania | 1,270 | 4,090 | 59 |

| Russia | 2,650 | 4,610 | 50 |

| Slovenia | 7,040 | 6,230 | less than 1 |

| Ukraine | 1,910 | 2,620 | 63 |

| Uzbekistan | 960 | 2,370 | 63 |

| Spain | 13,440 | 13,740 | – |

| UK | 18,340 | 17,970 | – |

Sources: a, b World Bank (1996), Table 1; c Milanovic (1997), Table 5.1; note: poverty line = US$4 per day.

The emerging dichotomy between Central Europe and Eastern Europe (including all of the former Soviet Union) is clear enough (Standing, 1996). People in the countries of the former Soviet Union and Romania (and, as Chapter 9 shows, Macedonia and Albania) have clearly suffered more through transition than people in Central Europe. As Table 1.1 demonstrates, Central European countries started their transition from a considerably higher base in 1989. Moreover, their relative political stability and geographic proximity to Western Europe allowed them to take advantage more easily of Western investment. However, even these countries suffered in spite of such advantages. In this book, four chapters deal with poverty and responses to poverty in these ‘luckier’ countries, and in Spain, which underwent a profound political transition in the midst of economic decline during the 1970s and 1980s. The remaining nine chapters concern poorer countries, ranging from Albania to Ukraine.

Institutions in the Communist state

What the above section shows perhaps most clearly is that there is considerable variation between economies in transition; they cannot be treated as facing similar problems and challenges, and it cannot be assumed that they require similar policy prescriptions. However, there are certain key institutional factors that were common to all Communist countries. Some of these factors have emerged as playing important roles in both facilitating and inhibiting responses to poverty in transition economies. Here we briefly examine four such factors: full employment and low wage inequality; the welfare state; housing; and an official denial of the existence of poverty. All of these factors have had an impact on the analysis of poverty and on responses to poverty in transition economies, and they emerge as themes that run through many of the chapters in this book.

Full employment and low wage inequality

One of the most important factors common to all Communist countries (and indeed, written into many of their constitutions) was the guarantee of full employment for all men and women – there was a job for everybody, and indeed most people had to work.1 This was in contrast to some Western countries such as the UK, where the employment of women, for example, was often discouraged (McLaughlin, 1994). Moreover, not only was employment guaranteed in Communist societies, but several key benefits such as childcare facilities, housing and even welfare payments were delivered through the enterprise (Atkinson and Micklewright, 1992; Jarvis, 1995). The maintenance of full employment was a critical element in the delivery of a wide range of social services under the Communist system.

Coupled with full employment was the ideologically driven desire to compress the distribution of earnings, and to ensure that manual workers, particularly those in heavy industry, were relatively well paid. Minimal income inequality was seen as a desirable goal in all Communist states, but as a policy, it was pursued with varying degrees of vigour. On the one hand, Gjonca et al. (1997) report that in Albania the highest wage income may have been less than twice the lowest income during the 1970s. On the other hand, Redor (1992) suggests that by the 1980s the structure of earnings in several Central European Communist countries was not terribly different to that in Western industrialised economies. Indeed, Burawoy and Lukács (1992) argue that steelworkers in US and Hungarian plants in the 1980s appeared to be offered very similar piece rates for their work. However, it is clear that both earnings and income inequality in pre-transition Communist countries was generally lower than that in most Western countries (Atkinson and Micklewright, 1992). This had implications for the analysis of poverty: low wage inequality and low income inequality ensured that...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Poverty in Transition Economies

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of tables

- List of figures

- List of contributors

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Poverty in transition economies: an introduction to the issues

- 2 The Russian homeless: old problem – new agenda

- 3 Impoverishment and social exclusion in Russia

- 4 Social assistance in Uzbekistan: can the mahallas target state support on the most vulnerable?

- 5 Income, poverty and well-being in Central Asia

- 6 Poverty profiles and coping mechanisms in Ukraine

- 7 Poverty measurement and income support in Romania

- 8 Albania and Macedonia: transitions and poverty

- 9 Estimation of poverty lines based on Ravallion's method: application to the Republic of Macedonia

- 10 Income distribution and poverty in Slovenia

- 11 A comparison of poverty in the UK and Hungary

- 12 Child poverty: comparison of industrial and transition economies

- 13 Poverty and social policy in a period of political transition in Spain, 1975-95

- 14 Targeting poverty benefits in Russia: reality-based alternatives to income-testing

- 15 Household budget and house conditions in two Russian cities

- 16 Coping strategies in Central European countries

- Index