eBook - ePub

The Economics of Joan Robinson

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Economics of Joan Robinson

About this book

Joan Robinson is widely regarded as the greatest female economist and the most important figure in the post-Keynesian tradition. In this volume a distinguished, international team of scholars analyses her extraordinary wide ranging contribution to economics.

Various contributions address:

* her work on the economics of the short period and her critique of Pigou

* her contribution to the development of the Keynesian tradition at Cambridge

* her response to Marx and Sraffa

* her analysis of growth, development and dynamics

* her comments on technical innovation and capital theory

* her preference for 'history' rather than equilibrium as a basis for methodology.

Her published work spanned six decades, and the volume includes a bibliography of her work including some 450 items which will be a major resource for students of the development of modern economic analysis.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Economics of Joan Robinson by Maria Cristina Marcuzzo, Luigi Pasinetti, Alesandro Roncaglia, Maria Cristina Marcuzzo,Luigi Pasinetti,Alesandro Roncaglia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

THE HERITAGE OF MARSHALL

1

JOAN ROBINSON AND RICHARD KAHN

The origin of short-period analysis1

Maria Cristina Marcuzzo

The most easily identifiable heritage of Marshall, in the `new' Cambridge School of Economics, is the short period. The short period of Keynes, Kahn and Joan Robinson has a peculiar meaning, whose origin can be traced back to the late 1920s and early 1930s. Those years saw the transition from the Treatise on Money to The General Theory and the transformation of the Marshallian-Pigouvian apparatus that culminated in The Economics of Imperfect Competition.

This paper is concerned with three points in particular. The first is the importance of Kahn's work in providing the link between the short-period determination of price and quantity of a single commodity and the short-period theory of the level of prices and output in aggregate. The second is comparison between Kahn's fellowship dissertation, The Economics of the Short Period, and Robinson's The Economics of Imperfect Competition, with a view to pointing out their common ground. The third point is the peculiarity of Joan Robinson's position as regards the importance of short period in economic analysis.

THE TRANSITION FROM THE TREATISE TO THE GENERAL THEORY

In his 1924 essay on Marshall, although showing his appreciation of the distinction between long and short periods, Keynes wrote: `this is a quarter in which, in my opinion, the Marshall analysis is least complete and satisfactory, and where there remains most to do' (Keynes 1972:206±7).

The task was undertaken by Kahn, who actually chose it as the topic for his dissertation, `The Economics of the Short Period'. This work, which Kahn started in October 1928 (Marcuzzo 1994a:26n) and completed in December 1929, earned him a fellowship at King's College, Cambridge, in March 1930. The dissertation turned out to be an important step in the development of Keynesian ideas, although, as Kahn remarked sixty years later at the time of its publication, `neither he [Keynes] nor I had the slightest idea that my work on the short period was later on going to influence the development of Keynes's own thought' (Kahn 1989:xi).

Kahn began his collaboration with Keynes in the final drafting of the Treatise, which was completed in September 1930;2 the same month saw the beginnings of his intellectual partnership with Joan Robinson.3 In fact, in the transition to the General Theory a major role is assigned by Moggridge to the `core pair' of Joan Robinson and Richard Kahn (Moggridge 1977:66).

We know that in the Treatise Keynes declared his unwillingness to be led `too far into the intricate theory of the economics of the short period' (Keynes 1971: 145),4 but soon after the publication of the book, in a letter to Hawtrey of 28 November 1930, he wrote:

I repeat that I am not dealing with the complete set of causes which determine volume of output. For this would have led me an endlessly long journey into the theory of short period supply and a long way from monetary theory;Ðthough I agree that it will probably be difficult in the future to prevent monetary theory and the theory of short-period supply from running together.

(Keynes 1973b:145±6)

It was while following this line of research that Keynes came to write his most famous book. The intention of writing the General Theory became apparent in the summer of 1932 after a period of long discussions with the participants in the Circus, who urged him to tackle the question of the causes of variation of output in aggregate. This at least is Kahn's opinion, who wrote: `It is my strong beliefÐ based on our several and joint memoriesÐthat the Circus encouraged the development indicated by Keynes to Hawtrey' (Kahn 1985:48±9).

One crucial element in the transition from the Treatise to the General Theory, Ðthe adoption of the theory of demand and supply, i.e. `in a given state of technique, resources and costs' (Keynes 1973a:23), to determine the short-period level of pricesÐwas attributed by Keynes himsel f to Kahn.5

As is well known, Kahn brushed aside any implicit or explicit suggestion that his role in the writing of the General Theory was that of a co-author rather than of a remorseless critic and discussant.6 However, in a letter to Patinkin of 11 October 1978 he wrote: `I claim that I brought the theory of value into the General Theory in the form of a concept of the supply curve as a whole and that this was a major contribution' (Patinkin 1993:659).

In order to clarify this question we have first to single out the relevant works produced by Kahn in this area. The obvious starting point is the so-called `multiplier article', to which Keynes refers, but this was written after the dissertation, which, as we have seen, was the first step in the development of short-period analysis. Two further works must be added to the list: the unfinished and unpublished book that has the same title as the dissertation, `The Economics of the Short Period', where the nature of the short period is further explored, and the lectures on the `Economics of the Short Period', which Kahn gave from 1931 onwards. These lectures came to us in the form of a summary of their main content, written by Tarshis on the basis of the notes he took when attending Kahn's lectures in the Mic haelmas term of 1932.

In the following section we shall take together the multiplier article, published in 1931, with Kahn's lectures, in both of which we find the construction of an aggregate supply curve of consumption goods and output in aggregate. We shall then go on to examine its bearing on the concept of the short period.

KAHN’S AGGREGATE SUPPLY FUNCTION

In his `multiplier' article, Kahn maintains that the determination of the level of price and output of consumption goods cannot but be derived from the theory of demand and supply.7 The aggregate supply curve of consumption goods, just like the supply curve of a single commodity, indicates the price necessary for each level of demand for consumption goods for that quantity to be produced, the demand for consumption goods being a function of total employment. Thus, the aggregate supply curve of the consumption goods sector represents `all the situations in which the price level is such as to confirm production and employment plans made by the firms in this sector' (Dardi 1990:8).

Following a change in employment (brought about by the building of roads financed by the government) we can study its effects on the prices and output of consumption goods, in other words the increase in production beyond the increase in investment, by looking at the shape of the supply curve of consumption goods. The latter must be derived according to `the point of view of the particular period of time that is under considerationÐlong, short or otherwise' (Kahn 1972:6).

As we know, Kahn claims here that:

At normal times, when productive resources are fully employed, the supply of consumption-goods in the short period is highly inelastic¼ But at times of intense depression, when nearly all industries have at their disposal a large surplus of unused plant and labour, the supply curve is likely to be very elastic.

(Kahn 1972:10)

Thus, in the former case, the increase in secondary employment is small and the increase in price high, while in the latter the change in secondary employment is large and the increase in price negligible.

The effects of a change in demand and in employment in the short period are made dependent on the state of detnand and the pattern of costs. Thus, in the short period, we can have an increase in output and employment, or only an increase in prices. If demand is sustained, the increase in costs (and therefore in prices) is accounted for by capacity being fully utilized. If demand is low, plants and machinery are not fully utilized and production can be increased without any increase in costs. If marginal costs are assumed to be fairly constant (because there is spare capacity since demand is low) there need not be a large increase in price to call forth an increase in output (the aggregate supply curve is elastic); in contrast, if marginal costs are increasing, because we are closer to full capacity, then prices also will increase or, rather, only if they increase will it be profitable to increase production.

Kahn's construction of the aggregate supply curve is meant to solve two problems: (a) what the price must be in order that a given quantity of consumption goods be produced; (b) how much employment is generated by the increase in the quantity of consumption goods that it is profitable to produce. However, the answers to these two questions are kept separate in his argument. The answer to (a) depends on the assumed pattern of costs, on the value and pattern of the elasticity of demand, and on the rule of behaviour assumed to be followed by firms (profit maximization); whereas the answer to (b) depends on the hypotheses about labour productivity and money wages.

Once hypotheses are made relatively to (a) and (b), we can calculate the increase in price and production for any given increase in the primary employment, which is of course the multiplier.

The multiplier article can be seen then as the first step towards a theory based on aggregate supply and demand curves, although its application is limited here to the consumption goods sector. Extension of this analysis to output as a whole is accomplished in the discussion of the aggregate supply function as we find it in the lectures given by Kahn in 1932. Unfortunately, the only published evidence we have here is contained in an article by Tarshis (1979), where he states that it conveys the substance of the argument put forward by Kahn in his lectures.8

The starting point for the construction of the aggregate supply curve is the same as in the multiplier article. The difference is that now on the vertical axis we have the expected proceeds necessary to induce entrepreneurs to produce a given output, while on the horizontal axis we can have the level of output (ASF-O)9 so that the questionÐwhat the price must beÐis substituted by what the proceeds must be in order that a given quantity be produced.

To derive the aggregate supply curve, we start from the determination of the supply curve of each level of output for a single firm. The supply price answers the question: given marginal and average costs, associated with a given level of output, Oi, what must the price be in order that the firm that maximizes its profits be willing to produce precisely that level of output?

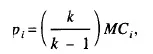

The level of output, Oi, will be produced only if profits are at a maximum; that is to say, only if in Oi marginal revenue equals marginal cost.10 Thus, for the well-known relationship between price and marginal revenue, for a given elasticity of demand measured at Oi, the supply price, pi, is:

where k=elasticity of demand and MCi=marginal costs at

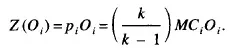

Oi. The supply curve is then given by:

Oi. The supply curve is then given by:

It is worth noticing that the above is a general formulation, which does not require special assumptions about market form or the shape of the marginal cost curve. Specific assumptions are reflected in the shape of the supply curve and in the value of its elasticity. According to Tarshis, the different possibilities were discussed in Kahn's lectures (Tarshis 1979:369n).

The aggregation problem is `solved' by assuming that, for any given level of output, the distribution among firms of their individual share is known. The aggregate level of output, O, is then:

m=number of firms; Ok=output produced by the k’th firm.

The total output of the economy is measured by a production index; to avoid double counting, intermediate products are of course subtracted from the total production, so that a measure in terms of value added is obtained.

The importance of the aggregate supply curve, drawn in the expected proceeds-aggregate output space, is that the derivation from it of the `level of prices' is straightforward: for each level of output, it is given by the ratio of expected proceeds to output. This means that the level of price can be determined by the same forces as the level of output and not by the Quantity of Money. This was an important step in the development of Keynesian ideas, as Joan Robinson reminded us years later: `A short period supply curve rel...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- CONTRIBUTORS

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I: THE HERITAGE OF MARSHALL

- PART II: IN THE TRADITION OF KEYNES

- PART III: FOLLOWING MARX, KALECKI AND SRAFFA

- PART IV: GROWTH, DEVELOPMENT AND DYNAMICS

- PART V: CAPITAL THEORY AND TECHNICAL PROGRESS

- PART VI: METHOD