![]()

Part I

Background

The word ‘plague’ had just been spoken for the first time

Albert Camus ([1947]2002:30)

![]()

1

Introduction

1.1 Introduction

Since ancient times, epidemics have repeatedly blighted the course of world history, necessarily involving widespread economic distress and always leaving a wake of human misery in their trail (see, for example, Cipolla, 1976).

The most common form of this form of catastrophe has been ‘the Plague’, referred to several times in the Bible; it was called shechin in classical Hebrew (see Hoenig, 1985 for the earliest known account of such diseases). In the Old as well as the New Testament, plagues appear, whether in the Book of Exodus, or the Book of Revelation. In Exodus [8:1] the threat of plague is used as a weapon of persuasion against the ancient Egyptians: ‘And the Lord spake unto Moses, Go unto Pharaoh, and say unto him, Thus saith the Lord, Let my people go, that they may serve me.’ As the Pharaoh desists, the ‘Ten Plagues’ ensue – with the ultimate desired effect.

Later, in the Book of Revelation, (6:1–8) the ‘First Horseman of the Apocalypse’ is called ‘Plague’, the other three being ‘War’, ‘Famine’ and ‘Death’. The four named horsemen are highly symbolic descriptions of different events that will take place in the ‘end-times’ but the only one the Bible names is ‘Death’; the others derive from the Bible’s descriptions. We also find them today featured in ‘modern myth-time’ in the older movie version of ‘The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse’ in 1921 and the more recent one, The Matrix in 1999.

The Plague was also noted in ancient Greek literary works, for example, by Homer in The Iliad and later by Thucydides in his History of the Peloponnesian War. This term in classical Greek can refer to any kind of illness; in Latin, the terms used are plaga and pestis. In antiquity, the two most devastating examples were the Athenian plague of 430 BC and the Justinianic plague of 542 AD. Plagues have also recurrently afflicted Imperial China for centuries, with fatalities running into millions (Benedict, 1988, 1993, 1996a,b).

The ‘Black Death’ that engulfed Europe from the fourteenth century onwards, was one of best-known examples closer to home, devastating both societies and economies, which Karl Marx interestingly drew attention to in Das Kapital (Marx, [1867]1977: Ch. XXV). Hunger and famine stalked the land and went hand in hand with the resultant decline in trade in the late medieval period and the Renaissance in the West (Herlihy and Cohn, 1997; Cohn, 2002). Rising mortality rates negatively affected both the demand for, and supply of, goods, services and the labour that went into them, then as now. ‘The Great Plague’ of 1665 killed one in five inhabitants of London: ‘Great fears of the sickness here in the City’ wrote the chronicler, Samuel Pepys, in his Diary, written from 1660 to 1669, this being his entry for 30 May 1665 (see Pepys, [1660–1669]1937:486). During the Great Plague, John Milton was forced to retire to Chalfont St Giles (his home), where he was able to finish his epic poem Paradise Lost. The English classical economist Thomas Malthus ([1798]1999) had studied the major impact of plagues on populations and economies, as checks on demographic growth (Pressman, 1999:29ff.). ‘Crises’ such as plagues had led to peaks of mortality that linked negative population changes and labour supply with key economic variables (Floud and McCloskey, 1994:60). However, Malthusian gloom was challenged on a number of counts; some economists saw technology as the ‘engine of growth’ in both agriculture and industry (Cipolla, 1976:136). The most recent severe health catastrophe of the last century was the global influenza epidemic that spread after the First World War; the so-called Spanish Flu allegedly killed more people than all those who died in armed combat (see Beveridge, 1977). It had a global reach and it wreaked a devastating path across all continents, not least in Asia. Such epidemics – as subspecies of ‘catastrophes’ in general – represent distinct exogenous, as well as endogenous, ‘shocks’ that have had far-reaching impacts on economic activity, as we shall see spelled out in the next chapter.

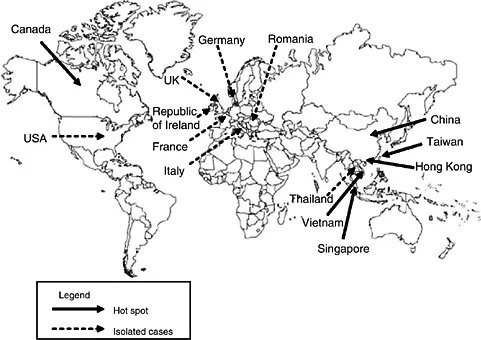

Not long into the millennium, in 2003, a new threat to humankind appeared in East Asia and was feared by some observers to be another replay of the 1918–1919 ‘flu’ disaster, namely what became known as the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic of recent time. Although to date this tragic episode seemed to have ended in July 2003, any complacency was to be misplaced, as it soon killed 916 people worldwide (see Figure 1.1 for the key countries involved), mainly in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR), and infected 8,422 others (World Health Organization, 2003a) as can be seen in Table 1.1.1 There have been few cases of the virus reported since but the outbreak left a legacy of fear in the countries that had been directly affected. Interest in SARS has now been displaced by the new threats of what is popularly known as ‘Avian Flu’, new and deadly varieties of which have hit the headlines in the last two years, of which more will be discussed later.

Let us now turn to what we hope to cover in this monograph. We intend to explore the ‘political economy’ of the SARS epidemic of 2003 in Asia, looking at its broadest dimensions, as policy and economy were inextricably entwined. Within this overall approach, we shall specifically deal with its impact on human resources, labour markets and unemployment.

Part I of this book first discusses the background of the SARS epidemic in terms of its historical, epidemiological, macro-as well as microeconomic

aspects and so on. Within it, Chapter 1 offers an overview, followed by Chapter 2 which sketches out an analytic framework of catastrophes, epidemics and political economy. The onset and spread of the SARS epidemic across the region will be spelled out in greater detail in Chapter 3. The wider economic impact of SARS, the consequence for labour markets and for human resources (HR) and human resource management (HRM) across Asia, will be set out in Chapter 4.

Part II considers the specific consequences in a number of key locations across Asia; for Hong Kong in Chapter 5; Mainland China in Chapter 6; Singapore in Chapter 7; and Taiwan in Chapter 8; followed by Part III, with Chapter 9 which looks at the broader implications, and Chapter 10 setting out our conclusions.

This specific chapter begins with an overview of the onset of the 2003 epidemic and then moves on to briefly discuss – in broad-brush strokes – the short-term economic impact of SARS on the Asian economies, labour markets and the particularly vulnerable service sector vis-à-vis its human resources. As we shall shortly see, epidemics, mortality and economics are now perhaps integrally linked, as mass air travel has become a potentially worldwide transmission-belt in the contemporary, globalized world.

1.2 Origin of SARS

The first fatal cases of ‘atypical pneumonia’, as it was initially called, probably occurred in Foshan, Guangdong Province in southern China, just next to Hong Kong, in mid-November 2002. A middle-aged village-committee official was sent to hospital with a suspected case of this apparently atypical pneumonia (Abraham, 2004); no one at the time had any notion that it would prove to be a major landmark in modern Asian history. Many hundreds of suspected cases were soon reported on the mainland, in Beijing and other major cities. The government of the PRC at first denied the news (se...