1 Tracing the economic

Modern art’s construction of economic value

Jack Amariglio

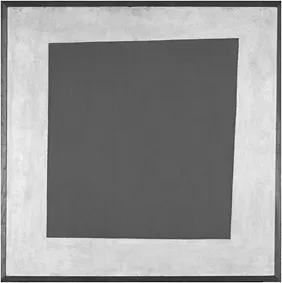

Image 1 Kasimir Malevich, Red Square: Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions.

Let us begin in Red Square. Well, at least somewhere in proximity to a red square. The red square I have in mind was painted in 1915 by the Russian Suprematist artist, Kasimir Malevich. The painting, entitled Red Square: Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions, was one in a series of works by Malevich in the midst of the turmoil and incredible burst of creative energy during and after the Bolshevik Revolution.1

In the view of the art historian Richard Brettell, “there is no more important social/aesthetic/political experiment in the history of modern art than Malevich’s Suprematism and its general offshoot, Constructivism” (1999, 40). As Brettell explains, Malevich was one of the originators of non-figurative and non-representational abstract art. But, if this is so, and if Malevich’s art stands somewhere relatively early in establishing the claim that art no longer has a connection to representation of an ostensibly material world, then in what sense can it be said that his work marks a social and political (and further, an economic) experiment? How can we connect in a meaningful way this revel into abstraction with the materiality of everyday life?2

Malevich was a superb polemicist. His work with a collective of other vanguard artists led him to construct, in words as well as image, what Brettell terms “a theory of autonomous, non-representational art” (39) that linked in a powerful way such seeming visual “self-referentiality” with social and economic forces that were thought, at the time, to replace an exhausted and discredited capitalism.3 In search of explanations for the vitality and revolutionary purpose—even the meaning inscribed—in such work, Malevich turned to what he called “the economic principle” (1992, 292–7). Malevich had little doubt that this economic principle constituted a “measure of our contemporary life,” and that therefore “we should apply this measure absolutely, to all forms of our expression, in order to be in accordance with the general plan for the contemporary development of an organism” (1992, 293). That this “economic principle” was defined both in terms of utilitarian ideals as well as Marxist or at least communist precepts may seem quite odd to the historian of economics, if not to aestheticians.

Malevich’s peculiar notion of the economic principle as the life force and that which is “represented” by his own squares and diagonals is a kind of excessive hybrid, a position in relation to notions of economic value that are quite often separated rather than combined in the official discipline of economics. In my view, to the extent that modern art—and here I simply use the convention of referring to art produced mostly in the West from the 1850s until at least the 1960s and 70s—can be read as contributing to economic discourse, one strong tendency within it has been the hybridization and then ultimate overflowing—codifying excess—of distinct notions of economic value.4 And, if there is a loose heading under which I would like to group all the forms of excess and intermixing that can be read as inscribing or tracing concepts of economic value within much modern art, and particularly that which is considered non-objective and abstract, it is the gift.5 I return to this point below. But, first, I foreground my discussion with a more general overview of the problem of art and economics.

Economic value and its representation in modern art

Art and economics. The connections, potential and actual, are numerous and substantial. The connections are ones that show up even in the realm of what is “represented,” that is, in what artworks depict as well as what they could possibly mean. For I have little doubt that the economic conditions surrounding the production, distribution, and consumption of artworks can be “read” in or into the works themselves.6 These conditions include everything from the facts that many artworks pass through art markets; that a subset is displayed in institutions that have been increasingly dependent on direct subvention by the state or by viewers; that they exist as luxury items in a world governed by commodity production and exchange; that they have rarely existed in the past 150 years completely “outside” market relations; and much else. One strong component of any approach to the intersection of artworks and the sphere of the economic is that art today is most often bought and sold and that, perhaps dripping from every pore, exudes all of the glitz, glitter, and gore that are presumed to come along with capitalist commodification.7

Yet, this essay has a different focus from what is termed (from John Ruskin forward) the “political economy of art.” While influenced by discussions of the social and economic conditions that have been part of artistic practice since the mid-nineteenth century, I focus instead on a different part of the problem: the question of how works of modern art may be read as constructive of economic discourses, and particularly discourses that presume notions of economic value, that is, the determination and effects of the economic “worth” of objects. My premise is that “the economy,” “the economic,” and “economic value” are represented, figured, and disseminated as images within modern art—or more to the point, they can be read as that which is gestured toward in such art.

This premise suggests two additional propositions. The first is that artists have been extremely important in generating and affecting the ways in which others understand economic ideas—ideas about what is and has economic value, how various economic activities work, how they can be known and measured, and much else. The second is that the constructions of economic value that can be read in much modern art diverge in important ways from—but also have a relationship to—the dominant modes of economic thought that have existed in the West since the mid-nineteenth century. “Modern art” is largely productive of an alternative or at least “altered” set of images, concepts, and discursive moments from those that comprise the core of the neoclassical, Keynesian, and sometimes even Marxian notions of economic value that have prevailed among late nineteenth and twentieth century academic economists.

On the first proposition, while I do not present here empirical evidence, such as that offered by Pierre Bourdieu (1984, 1993, 1995), David Halle (1996), Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Eugene Rochberg-Halton (1981), and others, about the ways in which artworks and cultural practices are popularly received, read, and/or used by audiences/consumers, this essay is guided by a point David Ruccio and I made in previously published work (2003) on economic discourses that are largely outside those that are found among academic economists. Ruccio and I argued that there is an integrity to these “everyday” or “ersatz” economics, and that, to some degree, the economic ideas of the “man in the streets” is derided by many academic economists because these ersatz practitioners hold views that are often critical or at least alternative to the most cherished theories held by those trained in universities.8

One place where people may be confronted with such alternative ideas about economics and value is in the realm of cultural practices and artifacts—and in artworks. Economic ideas do not originate or spread out purely from a center within the academy, but, rather, they are produced and learned in multiple sites, including the artworld, and as images and figures that are interpreted and/or read by anyone exposed to art. To settle this matter empirically, of course, would require an exploration into the actual reception of works of art in order to catalogue the determinate effects of art on economic ideas. For the purpose of this paper, though, I seek to establish a prior claim: the claim that modernist artworks can plausibly be read as “representing” economic ideas.

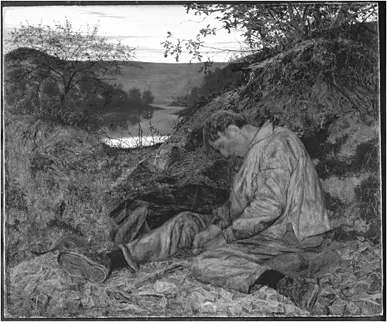

Image 2 Henry Wallis, The Stonebreaker.

The Stonebreaker and the value of labor

The issue of representation or reading for economic ideas or content is not hard, of course, when one is viewing a figurative painting like The Stonebreaker, rather than Malevich’s abstract “peasant woman,” even though the titles link these works in a very direct way.

In 2000, The Stonebreaker—painted in 1857 by Henry Wallis—was part of an exhibition at the old Tate Gallery. The exhibition, entitled “Ruskin, Turner, and the Pre-Raphaelites,” was organized around the collection of the great art critic and social thinker, John Ruskin. As I mention above, Ruskin is considered, along with William Morris, to have initiated an economic approach to modern artwork, or a political economy of art. In her superb text on economics and aesthetics in Victorian England, the literary critic Regenia Gagnier (2000) credits Ruskin, and then Morris after him, with focusing critical attention “not on the spectator or consumer but on the producer of the work and the conditions of production” (128). Gagnier claims that such a focus was not merely concerned with the conditions of a work’s emergence into the field of the artistic, but was also the aesthetic content itself, inscribed within valuable art. That is, one might say that Ruskin’s emphasis on the artist and the material conditions of the work as well as a work’s impact on the body were themselves interiorized as represented “within” and “through” a work of art.

The Stonebreaker, then, can be read as such an interiorizing work, since in it the work of the artist, Wallis, and the scene depicted do double duty in referring to the vicissitudes, pleasures, and difficulties of valuable labor. Yet, of course, there is a wonderful irony in the painting. First, the stonebreaker appears either asleep (and therefore at the end of a day’s work, as the sun sets) or worse (at the end of an occupation, threatened, of course, by industrial practices and machines that will, one day, replace this labor-intensive activity—relegated, later on, to the most onerous and degrading forms of doing penance, as on chain-gangs).9 That is, labor is not only implied in the worn, ragged body and clothes of the expended stonebreaker, but also in the simple tools and especially the stone shards that are strewn about the poor man as a nearly demented dispersion of wasted (but still noble) labor. It foretells of a time when the value of this once-skilled labor will stand in exact inversion to the difficulty and toil the task depicts (that is, it foreshadows the cheapening of such exhausted but knowing labor).10

It is a scene that emphasizes the solitariness of so much craft labor soon to pass out of existence, or to be collected and organized within workhouses and factories. The peace of this pastoral scene belies the tragedy of a world changing forever, and the stonebreaker seems poised, even if asleep, to haunt this brave new world with a reminder of what must, it is hoped, remain valuable within the new regime of labor discipline. In a way that will be repeated many times in modern art (even where there is no iconic reference to labor—that is, no “direct” representation of labor being performed), The Stonebreaker is one relatively early romantic attempt to come to grips with the fate of labor and labor value (here, identified largely with craft labor) in the wake of capitalism’s supposedly inexorable spread. The painting thus can be seen in a long line of work within modernism that constitutes an immanent critique of capitalist production and its destruction of the worker’s body if not the dignity and integrity of labor itself. And it raises the question of the valuing of labor’s product, and if there is, in fact, any virtue to be granted to an age in which cheapness due to mass production under conditions of alienated and exploited labor is the norm.

Gagnier’s take on Ruskin’s political economy of art connects Ruskin and Morris to the Marxist tradition of labor as the source and measure of economic value. While Ruskin more than Morris diverged in important ways from Marxian value theory, their writings, and the art of the Pre-Raphaelites, like Henry Wallis, promulgated an iconic view of labor value. William Morris, of course, is seen in this light as the great defender of the idea that the quality of artwork, and its ability to be perceived as aesthetically pleasing, is directly correlated with the conditions of the laboring artist and craftspeople more generally. In his 1883 lecture, “Art, Wealth, and Riches” (in Morris, 1993), Morris makes clear that it is the system of “competitive commerce” and its degradation of the worker and the worker’s craft—and here artists are accorded no exception—that is signified on the face of every ugly and vulgar object, including contemporary artwork. So, Morris implicitly endorses the idea that degraded labor, a consequence of competitive capitalism, can be transparently read as the submerged but still visible representation of art produced and consumed under that system. Morris’s view, then, sets up a simple hermeneutical strategy, one that sees in every surface of an artwork the inscribed conditions of production—which is why, when he turns to discuss what would lead to a marked improvement in aesthetic sensibility and output, he once again specifies transformed conditions of production—closer to craft socialism—as the determinants, but also the “meaning” that can be read in more aesthetically pleasing artifacts.11

I return to the question of the inscription of the conditions of production of artwork and labor’s value as signified in modern art when I consider the issue of so-called non-representational art. To preview one aspect of this discussion, the question becomes pertinent, assuming one shares Morris’s interpretive leanings, if modernist abstract art likewise can ever be read as a mirror of its own production. That is, can we read non-objective art as representing the quality and quantity of the labor that went into its production, as well as the degree to which the modern artist conceives and materially produces in degraded circumstances due to the immersion of art practice in a hyper-individualist commercial capitalism?12 And is there an equivalent aesthetic judgment implied if the answer is,...