![]()

1

Introduction

1.1 Understanding of the chronically poor

Bangladesh has made some progress in reducing poverty but still faces the reality that about 41 per cent of its population lives in poverty. This figure is about 41.1 per cent for rural areas. Of the poor, two out of three are caught in extreme poverty, as measured by the direct calorie intake (DCI) method [Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (2004)]. But because of population growth, Bangladesh entered the new millennium with the same absolute number of poor among its people as ten years earlier [World Bank and Asian Development Bank (2003)]. Significant reduction of poverty required a higher level of economic growth with social justice so that it reaches the poor and expands their opportunities. The economic growth elasticity of poverty in rural Bangladesh was estimated at −1.9 in 2000 and −1.8 in 1991–1992, while income inequality elasticity of poverty was 0.5 and 0.2 respectively [Sen and Hume (2004)]. These findings indicate that significant poverty reduction is not possible with the present level of economic growth if accompanied by high income inequality.

Until the 1990s, poverty was considered an absolute term, which is normally measured as the population living below a certain income level or threshold income. The measure of poverty by income is not sufficient and it ignores the deprivation of capabilities and opportunities. More recently, vulnerability and some basic dimensions of deprivation: lack of access to education, lack of access to health, lack of access to public and private services etc. have been considered in the measure of poverty.

To understand the chronically poor it is important to focus on poverty dynamics – the changes in well-being or ill-being that households experience over time. Understanding such dynamics provides a more sound basis for formulating poverty-eradication policies than the conventional analysis of national poverty trends. The understanding of chronic poverty is similarly complex, usually involving sets of overlying factors. Sometimes they can be intense, complicated, widespread and lasting.

Most chronic poverty is a result of multiple interacting factors operating at levels from the intra-household to the global. This is illustrated by Rina Begum’s and Mariam Begum’s livelihood story: their chronic poverty is an outcome of widowhood, lack of access to productive assets, a saturated labour market, unemployment, illiteracy, lack of better-paying job opportunities, early marriage, social injustice and poor governance. Some of these factors are maintainers of chronic poverty: they operate to keep the poor people poor for longer periods. Others are drivers of chronic poverty: they push the vulnerable non-poor and the transitory poor people into poverty that they cannot find a way out of (Box 2.1).

Many terms are used in Bangladesh to describe the poor, such as ‘absolute poor’, ‘extreme poor’, ‘hardcore poor’, ‘ultra poor’, ‘primary poor’, ‘secondary poor’ etc (CARE Bangladesh, 2003). Each term is used to separate the socio-economic characteristics of households. In the present study none of these terms is used, instead the households have been classified into the following categories of dynamic poverty groups based on their economic status.

• Non-poor (whose mean income or expenditure is always above the poverty line).

• Descending non-poor (whose mean income or expenditure was once above the poverty line but has now descended below the poverty line).

• Ascending poor (whose mean income or expenditure was once below the poverty line but has now moved above the poverty line).

• Chronically poor (whose mean income or expenditure is always below the poverty line and who remain in poverty for a long period of time). The distinguishing feature of the chronically poor is the long duration of poverty – i.e. people who live in chronic poverty and remain in poverty for a long period or for their whole lives. Many of them also inherit poverty and pass it on to their children. In a broader sense, chronic poverty refers to a greater extent of deprivation and denial of opportunities in education, health, material well-being, access to markets, productive assets, job security, political and social capital, and many other invisible factors.

There are some operational questions about regarding the assessment of households in these terms. Timewise, how long does a household have to be sliding into poverty before it can be deemed descending non-poor, how long should a household be out of poverty to be deemed ascending poor and how long should a household be in poverty to be deemed chronically poor. However, for the present context on average one to ten years was considered as the period of change of economic status, implying that if any household falls into poverty in one to ten years it is considered descending non-poor. Similarly, if any household moves out of poverty in one to ten years it is deemed ascending poor, while the chronically poor households inherited poverty and remained poor for more than ten years. The survey results indicate that about 65 per cent of the chronically poor inherited poverty from their parents and the rest experienced poverty after their households had become separated from their parents’ households for a longer period time.

1.2 The state of the chronically poor and its intergenerational mobility

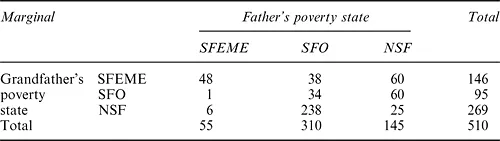

In the present context the term ‘state’ with three levels is used to describe the poverty status of chronically poor households so that a household able to provide sufficient food for three meals and bear educational and medical expenses may be termed State 1 (henceforth written as SFEME), a household able to provide sufficient food but unable to bear educational and medical expenses is termed State 2 (sometimes written as SFO) and a household unable to provide either sufficient food or bear educational and medical expenses is termed State 3 (sometimes written as NSF). During a field survey members of the chronically poor were asked to assess the poverty status of their grandfathers and fathers. Their assessment was verified with a senior member of the household and the father, if living, and in this way information on the poverty status of three generations was generated.

Analysis of intergenerational mobility of poverty status for the chronically poor households also indicated that only 48 grandfathers and fathers of 510 chronically poor households could provide sufficient food for all family members and could bear educational and medical expenses when they were household heads (Table 1.1).

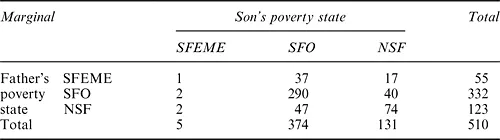

Table 1.1 shows that about 48 per cent of households showed upward mobility during the father’s period (one household moved from State 2 to State 1, six moved from State 3 to State 1 and 238 households moved from State 3 to State 2), while 158 or 31 per cent of the households showed downward mobility. About 21 per cent of households were immobile i.e. the poverty status of the grandfather and father remained the same through two generations. The poverty status has further deteriorated when sons formed separate households for their livelihoods. It is observed that 55 fathers could provide sufficient food and could afford educational and medical expenses, but only five sons could maintain that status (Table 1.2).

It is interesting to note that the majority (72 per cent) of chronically poor households lived in the same state of poverty and they remained immobile from the father’s period to the present time with a few exceptions. Only 10 per cent of households showed upward mobility (two households moved from

Table 1.1 Mobility matrix of poverty state for grandfathers and fathers of chronically poor respondents

Table 1.2 Mobility matrix of poverty state for chronically poor respondents and their fathers

State 2 to State 1, two from State 3 to State 1 and 47 from State 3 to State 2), while 18 per cent of households showed downward mobility. It transpires from Table 1.1 and Table 1.2 that the majority of the chronically poor inherited poverty from their parents and failed to improve their level of livelihood.

Since the emergence of Bangladesh, different policies and programs have been constructed to alleviate poverty in successive five-year development plans and various policy measures were designed to improve the well-being of the poor. Allocation in the Annual Development Programme (ADP) for poverty alleviation-related sectors has also been increased in nominal terms over the periods, from Tk.1200.00 mi...