1

A TYPOLOGY OF PRIVATE MILITARY/SECURITY COMPANIES

Introduction

This chapter attempts to establish a typology of the industry based around the range and scale of activities private military and security companies undertake. In this respect, the key conceptual distinction lies in PMCs’ resort to legitimate force: on whose behalf is that resort undertaken, and is it undertaken for the state, a public good, or for private gain? Based on commonly agreed characteristics of the companies, the chapter first attempts to categorise the industry by those working in this field. Here, the intention is to distinguish between the different types of private military and security companies, as well as individuals working as freelance operators. Next, an attempt is made to categorise the industry by examining the level of lethal force companies are either able or willing to project, and whether that projection has been taken in the public or private domain. This is achieved by looking at the intended purpose of that lethal force. Finally, by categorising companies, the chapter points to possible future impacts of PMCs and PSCs on international security.

There are problems associated with any attempt to categorise PMCs. In particular, the ability of individuals with a range of military skills to move between companies creates fluidity in the sector, increasing the range of activities and contracts a company can undertake. While some companies presume to be no more than a security company, they are able to undertake contracts normally associated with PMCs. As a consequence of this, it is easy for categories to become indistinct, especially when a company moves between governmental and commercial customers. Nonetheless, not to attempt to categorise companies will leave those who want to understand the nature of the business even more confused.

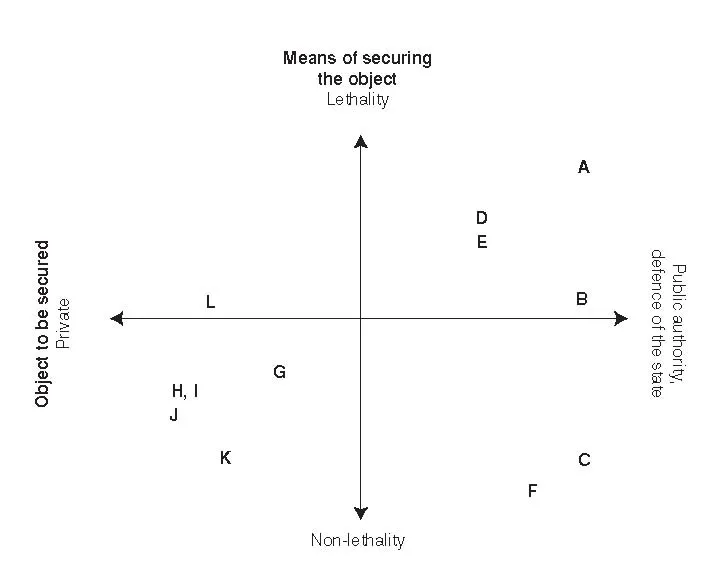

The first part of this chapter provides general definitions of the different categories companies fall into. These categories include private combat companies (PCCs),1 private military companies (PMCs), private security companies (PSCs) and freelance operators. The inclusion of the type of PSC represented by Group 4 Falck, and large engineering companies that undertake PMC type activities is necessary to indicate the extent of the sector, although the focus of the book remains PMCs and PSCs engaged in quasi-military operations. The second part of the chapter looks at how the potential use of different levels of lethal force by different actors in the public, or private, domain can be used to categorise companies. In this respect, companies are plotted on two axes; the horizontal axis representing what is to be secured, while the vertical axis pertains to the level of lethality used to secure the object. The final part of the chapter focuses on a cross section of PMCs and PSCs, detailing their characteristics. The chapter discusses the position of these companies on one of the axes, explaining also the general problems associated with categorising the companies by using this method.

Problems of categorising PMCs and PSCs

The categorisation of types of companies in any industry, or of the correspondence between them and the realities they typify, is a difficult task, more so in an industry that sees companies able to undertake ranges of activities that cut across different categories of services, as well as moving between vastly different customers. This point has not been lost on those researching the private security industry. While there is broad agreement about the distinctions between mercenaries, PMCs, and PSCs, such labels are not necessarily helpful, particularly in relation to regulation. As Lilly notes, acceptable definitions are hard to find, and the different entities tend to merge into one another.2 For example, how would we categorise a company such as ArmorGroup, able to supply military training and assistance, logistical support, security services, geopolitical risk analysis, and, if asked, crime prevention services through industry contacts, while the market for the company includes both commercial and government customers?3 ArmorGroup is not the only company with such an operational range. Many, though not all, major companies possess this range. Smaller companies on the other hand, particularly in the UK, have access through networks to individuals that allow them to buy in the expertise to give them whatever range of activities they require for a given contract. Thus, while companies on the whole tend to stay within their areas of core competence, especially multinational security companies, this is not always the case when examining the activities of ad hoc security companies in particular. All security companies, however, have the flexibility to move between different categories of service if they feel it would benefit their financial position in the long term. As Lilly has argued, it is more useful to define the activities that companies engage in, rather than the companies themselves.4 In reality, however, such movement between categories is unusual, especially when it comes to moving into the category of services covered by combat and combat support operations.

As Soyster points out, putting companies into categories is problematic, since companies often expand or contract their business or their focus.5 As such, even though many companies appear settled, they will still resist being categorised, lest market opportunities are lost as a consequence. The best that can be achieved is to ensure categories are wide enough to cover the general nature of the work companies undertake. In this respect, categories simply differentiate between companies, such as Group 4 Falck, who can be said to be at one end of the continuum, and Sandline International, until it closed for business in April 2004, which was at the other end. In the first example, Group 4 Falck’s business concerns are primarily to do with commercial security, and entail only the minimum use of lethal force. In the second example, Sandline International, concern is with combat support operations for a government and can entail the use of very high levels of lethal force. Companies between both these extremes tend to see their activities run into each other.

At the same time, many field staff working in the industry tend to be multiskilled. A single person, especially one retired from Special Forces, may have the necessary knowledge and skills to carry out more than one type of security task. Such individuals tend to move around the industry much more, covering a range of contracts from combat operations to commercial security protection. The criteria for them tend to revolve around money and whether they have the relevant skills necessary for a specific contract. Thus, the ability of individuals to cover a wide range of activities, while companies tend to remain within core competencies, has led to difficulties in constructing a typology of the industry.

Figure 1 Locating private military and security companies by the object to be secured and the means of securing the object

The axes

The following axes are designed to help to categorise PMCs. The position of different PMCs on the axes is shown in Figure 1.

Defining the limits of the axes

The following section describes the international environment represented by the axes. The axes represent only the international environment. The reason for placing the axes within an international context is because the companies themselves operate globally. Thus the object to be secured may not necessarily be in the company’s country of origin. Letters are used on the axes to represent both the companies and other organisations acting as controls, plotted on the axes. It is not intended for the axes to operate on a scale of numbers, using the number to determine the level of private and public interest and lethality. Instead, the companies are plotted in relation to each other, and three controlling agents as ‘ideal types’. The controlling agents for the vertical axis are conventional police, paramilitary police, and the army. These controlling agents represent different levels of non-lethal and lethal means. The conventional police are seen as representing largely non-lethal means, the army maximum lethal means, while paramilitary police occupy the middle of the axis. Public private partnership represents the controlling agent for the horizontal axis, occupying the middle of the axis.

The horizontal axis represents the object to be secured. At the private end, the object represents anything from a private property, a commercial building, an oil refinery, to a mine, and so forth. At the other end, public authority is understood to mean the defence of the state. In this instance, the state is recognised as representing a legal territorial entity composed of a stable population and a government.6 The vertical axis represents the means of securing the object represented on the horizontal axis. The bottom of the vertical axis is represented by non-lethal means employed by companies to meet their contractual obligations. Here, non-lethal is understood to mean that no lethal weapons are used to secure whatever the object being secured is. An unarmed guard of the type found in many modern shopping malls around the world comes very close to, or even occupies this area. Security is carried out without the use of any type of weapon, but is confined to reporting and potentially restraining transgression within a broader legal and police structure. The top end of the vertical axis is represented by lethal force, again employed by companies to meet their contractual obligations. Maximum lethality involves those techniques employed by an army fighting a war.

The axes provide four quadrants. In the bottom left-hand quadrant, security is a private commodity that can be purchased by anyone able to afford it. The security on offer is not deemed particularly violent, but, instead, can be described as relatively passive in response to the security offered in the top right-hand quadrant. Security companies working in this quadrant could be said to be working in a functioning social/political environment that enables the state to maintain stability. Moving up the line of lethality towards the top left-hand box would imply a deterioration of that environment as a consequence of the agencies of the state failing. The bottom right-hand quadrant represents an increase in state responsibility. In this quadrant, the state is deemed responsible for securing protection for society. At the extreme right-hand end of the horizontal line, no private security is available; security is the sole responsibility of the state. Companies working in this quadrant provide security services to the state. Security here represents a low level of lethality, and includes the supplying of private contractors as unarmed guards to government buildings or other public areas.

Moving into the top right-hand quadrant, state responsibility remains the same, while the level of security has increased to the strategic level. Here security is about interstate relations, while below it is more to do with domestic issues. The most prominent public institution responsible for security in this box is the military, able to exhibit maximum lethality under the control of the state. PMCs have also occupied this quadrant, although this is not a common occurrence, and has only really occurred in Africa. A reason for this may have to do with the inability of PMCs to project lethal force at the strategic level, while at the same time in support of the public good; Executive Outcomes’ (EO) operations in Angola and Sierra Leone being exceptions. Certainly in the West, armies are large enough and technically capable to undertake the role of protecting the state. As mentioned above, this has not always been possible, especially in African countries. Here one PMC in particular was active. During the 1990s EO provided public security for Angola and Sierra Leone. In both cases, EO played a prominent part in securing the local government. Even after taking Iraq into consideration, it is unlikely, however, that the private sector will play a significant part in this quadrant for the time being. As the Green Paper pointed out, EO’s success in Angola, and then Sierra Leone, may not be repeated.7

The final quadrant represents a political environment where state responsibility is in the process of breaking down, or has broken down completely, as in the case of Somalia. Here, security becomes a personal affair for the majority of local people. No longer is the individual able to rely on the state to secure themselves or their property, but instead has to either rely on themselves, local militias, or local warlords who are likely to levy some type of charge for this service. One could describe the political and social environment present at the extreme ends of the axes in this quadrant, as anarchy leading to chaos. Here, there is no government to govern the country, while violence is a factor in everyday life. In this respect, the quadrant is home to Kaldor’s new wars, where people become social beings and not judicial subjects.8

Private security in this quadrant is undertaken by a range of security companies from ArmorGroup protecting assets owned by oil or mining companies, through small ad hoc PSCs employing freelance operators prepared to act offensively, to mercenaries out to exploit the social conditions found in this quadrant. Companies working in this quadrant have to accept that they may have to employ lethal force to fulfil the conditions of their contract, narrowing the field of potential security companies willing or able to undertake the security work in this quadrant. This in turn favours the employment of small ad hoc PSCs employing freelance operators with the range of skills to be able to operate successfully. These companies have tended to keep a low profile, drawing very little attention to themselves from the media, which their clients, especially the large multinational companies, find beneficial. Finally, this quadrant is also the home of the classic mercenary prepared to undertake most types of security work whether legal or illegal.

Distinguishing between companies and freelance operators

The following section reviews the main characteristics of military/security companies and freelance operators and the distinctions between them. A clear understanding of the types of companies involved in trading in military/security services is a necessary prerequisite to further understand the nature of the industry. Without it, it is not possible to map out the size and scope of the privatised military/ security market, as well as the companies involved. The section first examines the hypothetical concept of a PCC, which is included because it helps us understand the extent to which war can be privatised. The fact that no PCCs exist at present has more to do with the lack of political will by states than with the ability of the market to establish such a company. Identifying the scope of the market for privatised war will enable us to separate out those military roles suitable only for state militaries, while allowing other military functions to be transferred to the private sector. The remaining sections are concerned with identifying the main characteristics of PMCs, proxy PMCs, PSCs and freelance operators. Unlike PCCs, such companies are a reality, and by separating them out in this way, we are better able to understand their purpose inside the security community.

Private combat companies

The purpose of a PCC is to highlight the extreme end of the spectrum. It is analytic and not, at present, real. Nic van den Berg,9 along with other EO colleagues came up with the concept during the 1990s. The closest to the concept we had in the past was EO and Sandline International. Both PMCs were prepared to undertake combat support operations. Neither was it considered a problem moving from a concept to a position of actuality. As with PMCs, PCCs would be dependent on databases for their personnel. Thus, turning the idea into reality would simply require carrying out the same functions as those necessary to mobilising a PMC. Nic van den Berg describes a PCC as a PMC specialising at the sharp end of the security industry, which meant undertaking solely combat operations, leaving combat support and logistics to PMCs. Continuing, he explains that the idea behind a PCC is to assemble a fighting force capable of b...