1

Conceptual framework and overview of themes

Frank Ellis and H.Ade Freeman

Introduction

This book arises from rural livelihoods research conducted in eastern and southern Africa in the period 2000 to 2003. The central theme of the book is the connection that needs to be made between patterns of rural livelihoods as they actually occur and the Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs) that are the centrepiece of government-donor efforts to reduce the incidence of absolute poverty in low income countries. It might be thought that this connection is obvious and hardly requires further elaboration, particularly given the efforts that are made to inform PRSPs by consultative exercises with civil society organisations and participatory poverty assessments.

However, such a presumption would be seriously wide of the mark. The reality is that despite their stated intentions to be innovative and cross-cutting documents, most PRSPs end up looking rather like sectoral expenditure plans, even a bit like those monolithic national development plans that were so popular three or more decades ago. Meanwhile, livelihoods are not like that at all; they are multiple, diverse, adaptive, flexible and cross-sectoral. Evidence provided in the chapters of this book suggests a serious mismatch between macro level poverty reduction strategies and the realities of micro level livelihoods.

This chapter provides an overview of the conceptual framework that informs the approach of many of the later chapters in the book, as well as a synthesis of the themes that bind the chapters together into a mosaic that seeks to shed light upon, and to take forward discussion about, the mismatch alluded to above. The starting point is the livelihoods approach to poverty reduction that provides a powerful framework within which micro-level experiences of poverty and vulnerability can be connected to the policy contexts that either block or facilitate people’s own efforts to escape from poverty. It is the livelihoods framework that permits apparently disparate dimensions and entry points into poverty reduction debates to be brought together in a reasonably unified way.

The Livelihoods Framework1

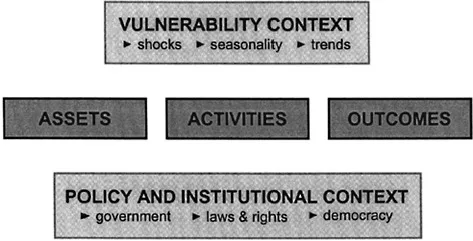

The term livelihood attempts to capture not just what people do in order to make a living, but the resources that provide them with the capability to build a satisfactory living, the risk factors that they must consider in managing their resources, and the institutional and policy context that either helps or hinders them in their pursuit of a viable or improving living. The basic livelihoods approach or framework is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

In the livelihoods approach, resources are referred to as ‘assets’ or ‘capitals’ and are often categorised between five or more distinct asset types owned or accessed by family members: human capital (skills, education, health), physical capital (produced investment goods), financial capital (money, savings, loan access), natural capital (land, water, trees, grazing etc.) and social capital (networks and associations). These asset categories are admittedly a little contrived, and not all resources that people draw upon in constructing livelihoods fit neatly within them. Nevertheless, they serve a useful purpose in distinguishing asset types that tend to have differing connections to the policy environment. For example, human capital connects to social policies (education and health), while natural capital connects to land use, agricultural and environmental policies.

It is worth mentioning in passing that the category social capital remains somewhat elusive as a guide to improving pro-poor policies despite a decade or so of academic musings about it (Harriss 1997). While it can readily be accepted that the quality of certain types of social connectedness can make a big difference to people’s livelihood prospects, this quality factor is difficult to pin down. For example, kinship ties can play roles both as valuable support networks and as demands on resources to meet familial obligations. Likewise, some types of social linkage seem more designed to keep the poor in their place than to assist them to overcome their poverty (bonded labour, caste systems and some types of traditional authority are examples).

Figure 1.1 The basic livelihoods framework (source: Ellis (2003a, 2003b).)

This caveat aside, the livelihoods framework regards the asset status of poor individuals or households as fundamental to an understanding of the options open to them. One of its basic tenets, therefore, is that poverty policy should be concerned with raising the asset status of the poor, or enabling existing assets that are idle or underemployed to be used productively. The approach looks positively at what is possible rather than negatively at how desperate things are. As articulated concisely by Moser (1998:1) it seeks ‘to identify what the poor have rather than what they do not have’ and ‘[to] strengthen people’s own inventive solutions, rather than substitute for, block or undermine them’.

As illustrated in Figure 1.1, the things people do in pursuit of a living are referred to in the livelihood framework as livelihood ‘activities’. Activities include remote as well as nearby sources of livelihood for the resident household; thus migration and remittances by family members is considered a category of livelihood activity, as well as crop production, livestock keeping, brick making and so on. The risk factors that surround making a living are summarised as the ‘vulnerability context’, and the structures and processes associated with government (national and local), authority, laws and rights, democracy and participation are summarised as the ‘policy and institutional context’. People’s livelihood efforts, conducted within these contexts, result in outcomes: higher or lower material welfare, reduced or raised vulnerability to food insecurity, improving or degrading environmental resources, and so on. Figure 1.1 is consciously devoid of arrows implying causality or feedback. Livelihoods are complex and changing. Although of course they encompass links between cause and effect, as well as cumulative processes, these cannot be captured adequately in such a simplified representation.

The livelihoods approach sets out to be people-centred and holistic, and to provide an integrated view of how people make a living within evolving social, institutional, political, economic and environmental contexts (Carney 1998a; Bebbington 1999). It has proved to have considerable strengths, especially in recognising or discovering:

- the multiple and diverse character of livelihoods (Ellis 1998, 2000);

- the prevalence of institutionalised blockages to improving livelihoods;

-

- the social as well as economic character of livelihood strategies;

- the principle factors implicated in rising or diminishing vulnerability;

- the micro-macro (or macro-micro) links that connect livelihoods to policies.

Migration and vulnerability as illustrations of the approach

This section provides two interwoven illustrations of how the livelihoods approach can be utilised to gain a clearer understanding of particular development issues. One is migration, understood as a spatial separation between the location of a resident household or family, and one or more livelihood activities engaged in by family members. The other is vulnerability, defined as the proneness of a household or family to acute food insecurity when confronted by a calamitous event like a drought or flood. Different types of migration are one manifestation of the more general phenomenon of livelihood diversification (Ellis 1998, 2000), and many of the arguments that follow about migration apply also to other forms of diversification.

Migration is a central feature of the livelihoods of the majority of households in low income countries. The immediate connections to the livelihoods framework in Figure 1.1 are to human capital (migration involves mobility of labour, together with a person’s experience, skills, education level and health status), and to the set of activities that comprise the occupational portfolio of the household. More than this, however, different types of migration play multiple roles in reducing the vulnerability of households, and in potentially enabling virtuous spirals of asset accumulation that can provide families with exit routes from poverty.

It is nowadays well understood that vulnerability is different from poverty. Poverty, certainly as defined by economists, describes a state with respect to an absolute or relative norm (e.g. a poverty line). Vulnerability, by contrast, refers to proneness to a sudden, catastrophic, fall in the level of a variable, usually interpreted as access to enough food for survival. The phrase ‘living on the edge’ provides a graphic image of the livelihood circumstances that vulnerability tries to convey. This phrase evokes the sense of a small push sending a person or people over the edge, and it is just this knife-edge between ability to survive and thrive, and sudden loss of ability to do so, that the term vulnerability seeks to describe (Ellis 2003b).

Two factors that predispose rural poor people to vulnerability are seasonality and risk. Both these factors can be ameliorated by migration. Seasonality causes what is known as the ‘consumption smoothing’ problem (Morduch 1995). Income flows, for example from crop production, are uneven relative to the constant needs of food consumption. The migration of household members to take advantage of differing seasonal patterns of farm production elsewhere (rural—rural migration) and of non-farm jobs in the off-season (rural—urban migration) are responses to the seasonality problem, and several case studies of these patterns have been detailed in recent literature (de Haan and Rogaly 2002; Rogaly et al. 2002). For food insecure rural households, out-migration of family members in the peak food deficit season may be essential for the survival of the resident group that stays behind by reducing the number of people to feed (Toulmin 1992:51; Devereux 1993:53)

Poor rural households in low income countries construct their livelihoods in a risky environment. They are prone to the personal shocks of chronic illness (including HIV/AIDS), accidents, and death as well as confronting natural hazards and market instability. Risks are reduced by diversifying livelihoods. This risk amelioration can, to a limited extent, occur in situ, for example by diversifying cropping patterns on farms or by combining farm and non-farm activities in the same location. However, because agriculture-related activities like crop processing or trading collapse when harvests collapse, more effective risk reduction occurs by spreading risk across assets and activities that have different types of risk associated with them. This is where migration comes in, because it provides just such a spread of spatially separated activities with differing risk profiles.

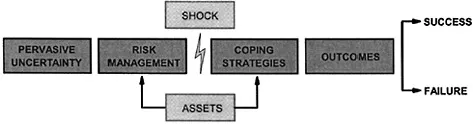

Vulnerability can be portrayed as a risk sequence (Figure 1.2), making it clear how it connects to the livelihoods approach as well as where migration fits into the picture. This also acts as a bridge to poverty reduction aspects of migration. Poor households build their livelihoods in a context of pervasive uncertainty comprising the seasonality and risk factors already described, as well as, quite often, political and governance risks. They are used to this, so they manage risk as best they can, and migration can play a pivotal role in helping them to do this. If a shock occurs (either a personal shock or a wide-spread shock like rainfall failure), they adopt coping behaviours to reduce the adverse impact of the shock, and, again, migration plays a significant role here. Coping strategies produce outcomes: relative success or failure at dealing with the shock. In the extreme case (‘people fleeing drought’), resident livelihoods collapse and entire families go on the move.

Critical to the degree of vulnerability represented by risk management and coping within the sequence illustrated in Figure 1.2 is the asset status of the households and how this is changing over different time periods (see also Chapter 2). In general terms, the higher the level and the more diverse the assets owned by the household, the greater its capacity to manage risk and cope with shocks, i.e. the less vulnerable it is. So far, we have referred to migration principally in terms of one category of asset, namely labour, the mobility of which helps to ameliorate seasonality and risk. However, the asset effects of migration go further than this. The earnings obtained from migrating, and the remittances sent back by migrants to their resident families, are critical to maintaining or raising the level of other assets: savings, land, equipment, livestock, education of children and so on. Migration also widens social networks and consequently increases so-called social capital.

Figure 1.2 Vulnerability as a risk sequence (source: Ellis (2003b).)

In order to move out of poverty, poor households have to increase the assets that they can deploy productively in order to generate higher incomes. Numerous studies have observed that moving out of poverty is a cumulative process, often achieved in tiny increments. Assets are traded up in sequence, for example, chickens to goats, to cattle, to land; or, cash from non-farm income to farm inputs to higher farm income to land or to livestock (Ellis and Mdoe 2003; Chapter 3 this volume). A critical constraint slowing down or preventing such ‘virtuous spirals’ is the inability to borrow or to generate cash (often discussed under the rubric of credit market failures). For this reason, earnings or remittances from migration can play a pivotal role in initiating and sustaining such cumulative processes. Nor do the cash flows have to be large in order to do this. In the context of so-called dollar-a-day poverty i.e. when the poor are defined as those getting by on under the equivalent of a dollar per day worth of consumption per person, very small amounts of additional cash can make significant differences to the options available to people to get a toehold on ladders out of poverty.

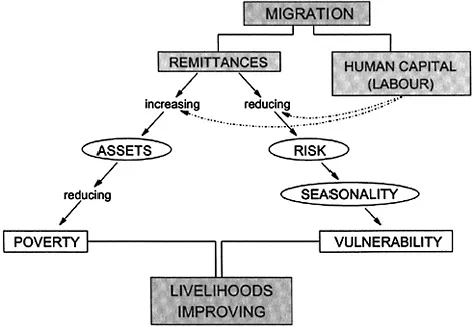

The connections discussed in preceding paragraphs are summarised in Figure 1.3, which displays the fundamental ways that migration and remittances can help to reduce vulnerability and poverty for people trying to put together adequate and improving livelihoods. The following list represents some of the positive ways that earnings and remittances from migration can strengthen rural livelihoods:

Figure 1.3 Positive links between migration and improving livelihoods, (source: Ellis (2003a).)

- investment in land, or land improvements, including reclaiming previously degraded land (Tiffen et al. 1994) provided one of the better-known examples of this for Machakos district in Kenya);

- purchase of cash inputs to agriculture (hired labour, disease control etc.), resulting in better cultivation practices and higher yields (Carter 1997);

- investment in agricultural implements or machines (water pumps, ploughs etc.);

- investment in education, resulti...