![]()

1 Introduction

The economic—security nexus in Northeast Asia

T.J. Pempel

Security analysts typically assess the dynamics of the Northeast Asian region primarily in military and hard security terms. This book begins from a different premise. It is a shared consensus among the contributors to this volume that relations among the states of Northeast Asia are far more comprehensible when the interactions between economics and security are considered simultaneously. Beyond the simple empirical light that these chapters shed on regional relationships however, they also utilize the experiences of Northeast Asia to shed light on a central puzzle that has ensnared political scientists and policymakers since at least the time of Immanuel Kant and Adam Smith: how do economic and security relations interact? Northeast Asia, we believe, provides a tantalizing laboratory within which to examine the relationships between economics and security primarily because of the complex but sustained interactions between the two within the region. More explicitly stated, this book begins with two related goals: first, to examine the linkages between economics and security in an effort to understand more fully the complex relations among the major states of Northeast Asia; and second, to utilize an empirical examination of those relationships to shed more light on the often studied linkages between economics and security at a general level.

At least three elements are central to our analysis and to the general puzzle of how economics and security are connected. First, Northeast Asia has long been plagued by a trove of security tensions that make it, in the oft-cited phrase of Aaron Friedberg (1993), a region “ripe for rivalry.” Second, particularly in the period since the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997–98, economic interdependence has risen sharply in Northeast Asia as the result of cross-border investments, financial coordination, trade, and the development of transnational production networks. Third, and ironically, despite its deep security and geopolitical fissures, Northeast Asia has been free of any actual state-to-state wars since the Korean armistice was signed in 1953. Add to these still a fourth fact—that the region has for at least a decade been undergoing an extensive power transition based on the rapid development of China—and the relationships between security and economics within the region defy easy linear conclusions about causal connections, particularly in so far as the power transition may well mean that past experiences are but weak predictors of the future.

Among the empirical questions that the region poses: What is the role of economics in how the states of the region define their “security?” How do bilateral relations in hard security issues such as territorial disputes or more culturally-rooted issues such as historical memories, between China and Japan, Japan and Korea or China and Korea link to the bilateral economic relations among these countries? How do different patterns of techno-nationalist development play into regional security ties? Do closer economic connections enhance or detract from a nation’s security, questions being asked, for example, in Taiwan, Korea, and Japan vis-à-vis deeper ties with China?

Answers to such questions can shed important light on a series of more abstract questions addressed usually at the global, rather than the regional level, by scholars of international relations: How much does economic interdependence account for the absence of shooting wars, a claim many adherents to commercial peace theory might suggest? Do the costs of geopolitical confrontation simply become too high as a consequence of the region’s rapidly growing economic linkages? If so, how does one explain the persistence of security tensions short of overt warfare? Are outbreaks of periodic saber-rattling and bellicose rhetoric simply examples of geostrategic brinksmanship, signaling, and efforts at satiating domestic public opinion, but with the final escalatory step to shooting wars being jointly avoided? Does enhanced economic interdependence actually have a slow moving but generally positive spillover in the reduction of military tensions or conversely, do states respond to ongoing security challenges by attempting to leverage their enhanced economic ties into geostrategic bargaining chips? And to what extent do the answers to any of these questions lose predictive power in the face of a global or regional power transition?

This book attempts to shed light on these and other empirical and more abstract questions about the interactions between economics and security. To set the stage for the chapters that follow I begin by outlining the four points noted above—the security tensions that continue to bedevil the region; the region’s growing economic interdependence; the absence of state-to-state warfare; and the shifting power relationships.

Security tensions in Northeast Asia

Northeast Asia has one of the world’s heaviest concentrations of lethal military force. Three of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, all of whom were original nuclear weapons states (the United States, China, USSR/Russia), have an ongoing security presence in the region. The DPRK has twice tested nuclear devices and has also demanded recognition as a nuclear power. Meanwhile, at least three other governments (the Republic of Korea (ROK), Taiwan, and Japan) have the technical capability to “go nuclear” on short notice. Conventional armaments are extensive with China (1.6 million), the United States (1.4 million), and the DPRK (1.1 million) having the most extensive active-duty military forces with additional numbers in active reserves. Conventional weapons for air and sea combat are also sophisticated and extensive (e.g. International Institute for Strategic Studies 2010; Cordesman 2011). Furthermore, “both the U.S. and China have nuclear-armed aircraft and ICBMs, IRBMs, MRBMs, and SRBMs with boosted and thermonuclear weapons” (Cordesman 2011: 10). The DPRK, in addition to its nuclear weapons and conventional armaments, has extensive chemical weapons and is suspected of possessing biological weapons. Add in such items as extensive and integrated command and control system as well as communications, anti-ballistic missile defenses, satellites, cyber-warfare capabilities, and the like and it becomes very clear how extensive the dispersion of extremely sophisticated military capabilities across the region really is.

These militaries have been built up partly in response to, but also serve to exacerbate, tense relations in a variety of flashpoints. Since the reunifications of Vietnam and Germany, Northeast Asia now contains the largest concentration of divided polities in the world (Kim 2004). Incomplete national consolidation struggles are the pivot for relations between the two Koreas and between China and Taiwan. Cross-Straits tensions have ebbed and flowed as the two governments on either side have challenged the very legitimacy of the unsteady status quo. Since the inauguration of Ma Ying-jeou as Taiwan’s president, cross-Straits relations have been far less frosty, but the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as recently as 2005 passed a law threatening to use military force to reunite Taiwan with the mainland if it presses its case for independence too vigorously. Taiwan has hardly been militarily oblivious to the security posture of its gargantuan neighbor and purchases of sophisticated arms, particularly from the United States, are used to offset possible PRC threats.

Relations between the two Koreas have been equally mercurial and as of this writing are being heavily shaped by the sinking of the ROK’s naval vessel, the Cheonan (March 2010), and by the DPRK’s shelling of Yeonpyeong Island (September 2010). The ROK blames the DPRK for what it claims were unprovoked attacks while the North denies involvement with the Cheonan and blames ROK and U.S. military maneuvers in contested waters as the reason for the shelling of Yeonpyeong.

Beyond these two cases of divided nations, the region is rife with a number of unresolved territorial disputes, most of them legacies of World War II and the Cold War. These remain sources of ongoing rancor and military threats. So too do a number of historical memories of past wars, occupations, and military actions. These regularly poison contemporary relations while divergent political and economic systems, along with religion and culture, also fragment rather than bring together the region’s diverse states. It is little wonder that scholars refer to Northeast Asia not only as a “region ripe for rivalry” (Friedberg 1993), but also as a “cockpit of great power rivalry” (Holbrooke 1991: 48), “the cockpit of battles” (Van Ness 2003), and a system of long-run, unstable multipolarity (Mearsheimer 2001: 381) moving “forward to an unhappy future” (Buzan and Segal 1994: 18).

Economic interdependence

Economic development has become a major agenda item for virtually all of the political and business elites in Northeast Asia. Governments have in their diverse ways played a substantial role in the economic development of most of the economies in the region. Indeed, as Tai Ming Cheung shows in his contribution to this volume, all Northeast Asian governments have pursued extensive public policies designed to shape their explicit strategies of techno-nationalism. At the same time, the region has also manifested an extensive rise in economic interdependence driven primarily by waves of commercial integration. The combination of trade and foreign direct investment fueled the region’s collective growth and its enhanced interdependence starting as early as the 1980s. Simultaneously, as East Asia’s economies moved toward greater interdependence, Asian-based multinationals also integrated themselves more efficiently into the global economy with the result that the region as a whole moved toward becoming an integrated “Asian factory” (Ravenhill 2008; inter alia).

Japanese corporations and the Japanese government, bolstered by the rapidly rising Japanese currency, were the initial drivers of these regional production networks (Katzenstein and Shiraishi 1997; Pempel 1997; inter alia). In Japan’s case, the regionalization and internationalization of manufacturing became evident when in 1995 Japanese-owned companies were manufacturing more overseas (¥41.2 trillion) than they exported from the home islands (¥39.6 trillion) (Kubota 1994; Far Eastern Economic Review 4 July 1996: 45). Soon, however, investment from firms based in Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore, and elsewhere was also flowing across national borders. Individual companies from countries with rapidly escalating currencies began heavy investments in other Asian countries that could offer cheaper land and labor, thereby diversifying their production processes across several different countries. Simultaneously, ethnic and family ties among diasporadic Chinese business people became the basis for linking together what Naughton (1997) has called the “China circles” across “Greater China” (Katzenstein and Shiraishi 1997; Pempel 2005). Equally, China’s rise expanded economic opportunities for firms from Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan (Perkins 2007: 47), while more recently, China itself has become increasingly the source of considerable outgoing FDI.

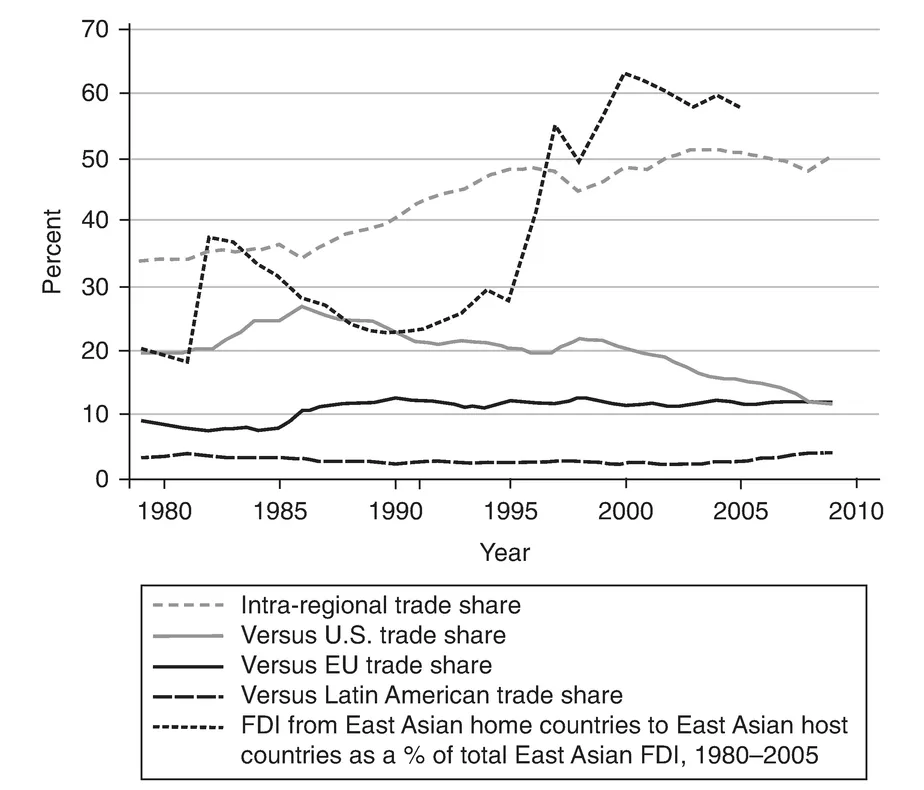

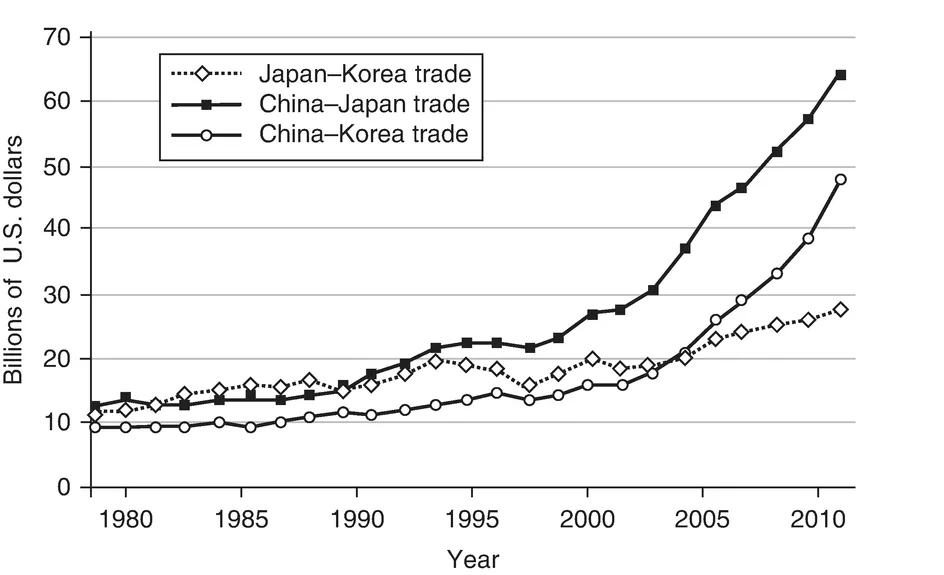

Intra-East Asian investment has taken a sharp turn upward, particularly since the mid-1990s, and the cumulative effect of these moves has been a substantial increase in cross-border production. This in turn has bolstered enhanced intra-Asian trade and a deeper East Asian interdependence while at the same time reducing the previous East Asian dependence on exports to the United States. By 2008, intra-Asian trade had risen to 56 percent of total Asian trade, a figure close to that of the EU while Asian reliance on the U.S. market was on a downward trend (see Figure 1.1). Interdependence in trade within Northeast Asia more specifically has risen in tandem, creating an extensive economic interdependence among Japan, China, and the ROK (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1 East Asia’s linked trade and investment.

Source: Goldstein and Mansfield 2011.

Figure 1.2 Intra-regional trade in Northeast Asia.

The states of Northeast Asia have also been moving in many common strategic directions and closer cooperation in the area of finance. China, Japan, and the ROK have all opted for strategies of expanded foreign reserve holdings in the aftermath of the Asian Financial Crisis that Gregory Chin (2010) has labeled “self-insurance’’ and “regional insulation” against the previously disruptive forces of global capital and “hot money” that were such a challenge to much of East Asia in 1997–98.

Financial cooperation has also been shown in the development of the Chiang-Mai Initiative and its subsequent multilateralization (CMIM). CMIM has put in place a currency swap mechanism for the region. Its establishment showed a particularly high level of financial cooperation among the ROK, China, and Japan in which the three reached collective agreement on the division of financial contributions that each would make. Similar financial cooperation was also shown in the development of the Asian Bond Markets Initiative aimed at reducing the region’s dependence on global capital financing in U.S. dollars and/or on the London and New York exchanges, instead moving toward the use of Asian capital for Asian development projects.

Northeast Asian governments have also been active in the pursuit of preferential trade agreements (PTAs). Many of these have expanded existing corporate-based trade links; others seek to expand the economic linkages to include economic cooperation and technology-sharing arrangements as well (Dent 2003, 2005; Aggarwal and Urata 2006; Pempel and Urata 2006; Aggarwal and Koo 2008; Oba 2008; inter alia). And as Koo (2009) demonstrates persuasively, the pursuit of such PTAs has been a fundamental element in the regional and economic strategy of several countries, but most particularly, the ROK.

In striking contrast to these webs of economic interdependence, North Korea has stood out as a conspicuous exception. As Imamura’s detailed analysis shows, there would be numerous economic reasons for the North to have tried emulating China’s and Vietnam’s economic reforms. But the combination of political fears, a focus on diverting limited resources to military forces, along with deep-seate...