- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Structural Economics

About this book

This book aims to make the nature of input-output analysis in economics clearly accessible and, contrary to the opinion of many commentators, shows that this type of analysis can be compatible with the doctrines of neoclassical economics.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

National accounts and economic analysis

1 National accounts, planning and prices

Introduction

Input–output (I–O) analysis was invented by Wassily Leontief, who received the Nobel Prize for this achievement in 1973. Rudimentary ideas came about when Leontief (1925) thought through the problem of setting up national accounts in the Soviet Union. Input–output analysis orders national accounts in a suggestive way, which is useful for planning. Professor Leontief has contributed to the planning of the United States war economy of 1940–45. During the cold war, I–O analysis was surrounded with suspicion, because of its use in central planning, and became out of fashion. Neoclassical economics, the analysis of utility maximizing individuals and profit maximizing firms, whose actions are coordinated by the invisible hand of the price mechanism, became predominant and its results about the optimality of the free market have wide impact to date.

Input–output analysis is thought to specialize in quantity relations between levels of outputs of the various sectors of an economy. It may also account for cost components, but is thought to do so in a mechanical way, independent of the levels of outputs. I refer to Leontief (1966, ch. 7). Conversely, neoclassical economics is thought to focus on the price system, with limited capability to explain or prescribe levels of outputs, particularly when production is characterized by so-called constant returns to scale.

Samuelson (1961) has shown that in a neoclassical model, I–O proportions will be fixed, if there is only one factor of production (labour, say). If there are more factors of production (e.g. labour and capital), I–O analysis and neoclassical economics can still be considered two sides of one coin. Perhaps I should add a personal note to explain how I came to ponder about the connection. When I was a PhD student, I was research assistant to Wassily Leontief, but my thesis advisor was William Baumol, who is notorious for his neoclassical views. However separate the two schools of thought operated, even within one and the same Department of Economics, I considered it a challenge to reconcile the two approaches. This chapter attempts to render an account of my thinking. To bridge I–O analysis and neoclassical economics, I will use the mathematical theory of linear programming.

Neoclassical economics, particularly general equilibrium analysis, is relatively close to mathematics and, therefore, determines by and large the perception of economics by mathematicians. It is my hope that this chapter narrows the gap with applied economics. The chapter proceeds from the practical to the theoretical, in an admittedly uneven manner. The first section introduces national accounts and their use in planning. The second section is an excursion to some dynamic aspects. I include it to draw the attention of interested mathematicians to some matrix issues, which may be skipped, but not the third section, which is central. It developes an essentially competitive price theory in an I–O model of an open economy. The fourth section discusses further links with neoclassical economics.

National accounts and planning in one lesson

Input–output analysis puts order and structure in national accounts. Historically, the order component came first. When the Soviet accounts were organized, Leontief detected some double counting. To get a feel for this, consider the following production of consumption goods from raw materials. Mining yields iron ore, it is processed by the steel industry; manufacturing makes the final product. Now, if you would add the outputs of the three sectors to the national product, you would be accused of double counting. To understand why, stick in an imaginary sector between the steel industry and manufacturing that wraps steel. The wrapping sector purchases steel and sells wrapped steel. In the process, it would contribute the same amount to the national product as the steel industry. The problem of eliminating double counting from national accounts is nontrivial, because production is not directed as in our example, but roundabout. All sectors purchase from and sell to each other. Input–output analysis disentangles this. Moreover, it can be used to add structure to national production. By assuming that I–O ratios are constant in sectors, one can analyse the production requirements of sustaining alternative bills of final goods, such as a war effort. When the United States participated in the second World War, it was so late that the government did not want to rely exclusively on the price mechanism to sustain the defence industry. Production was planned, using I–O analysis as a tool.

I need notation. Divide the economy into n production sectors, including the ones mentioned in the example (here n is an integer). The first sector, mining, say, sells, per unit of time, amounts x11, …, x1n to sectors 1 through n, and y1 to final demand, that is households, government, net exports and for investment. Table 1.1 organizes these data in rows and adds a row v1, … , vn which will be explained here.

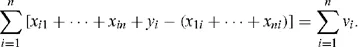

Now consider a column, say the first one: x11, …, xn1 are the amounts purchased by sector 1 from sectors 1 through n. Thus, sector 1 receives x11 + ··· + x1n + y1 and spends x11 + ··· + xn1 on material inputs. The difference defines v1, value added. It consists of wages, capital returns, profits and taxes. Note that if we do so for all sectors, i, and sum, we obtain

Table 1.1 Input–output table

| Sales of sector 1 | x11 … x1n y1 |

| Sales of sector n | xn1 … xnn yn |

| v1 … vn |

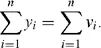

In the left-hand side all x terms cancel out, hence

| (1.1) |

This is the well-known macroeconomic identity of national product and national income. By definition, national product includes only final demand items, and national income only outlays on non-material input. Double counting is avoided by exclusion of all intermediate flows. Note, however, that the interaction between all sectors invalidates a sectoral breakdown of the equality of national product and national income. In other words, (1.1) does not necessarily hold term by term.

Sector 1 has material inputs x11, … , xn1 and output x11 + ··· + x1n + y1. x1 is common shorthand for the latter sum. Dividing the inputs by the output we obtain tec...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I National accounts and economic analysis

- Part II Input–output coefficients

- Part III Methodology

- Part IV Dynamics

- Part V Productivity

- Part VI Services and trade

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Structural Economics by Thijs ten Raa in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.