eBook - ePub

Exchange Rate Policies in Emerging Asian Countries

- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Exchange Rate Policies in Emerging Asian Countries

About this book

The future emergence of a European monetary zone is set to transform the configuration of the international monetary system and the roles of the dollar, the Euro and the yen within this system. This book addresses this issue with discussion of:

* exchange rate policies pursued in the principal Asian countries

* the measurement of equilibrium exchange rates for these countries

* the maintenance of the dollar peg by Asian currencies

* the absence of a trend to monetary regionalism based on the yen

* the outlook of regional monetary co-operation

* the outlook of regional monetary co-operation

Case studies pay particular attention to Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Thailand.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

EXCHANGE RATE POLICIES IN ASIA

The evidence

1

FLEXIBILITY OR NOMINAL ANCHORS?

Rüdiger Dornbusch and Yung Chul Park

The issue of exchange rate policy in Asia comes up in a large variety of ways. In the past, being competitive was most of the message. Today, the range of challenges seems to have become far wider. And even if it has not, contrary to our contention, it is well worth reassessing whether past policies have been productive. In fact, though, new considerations come from all sides:

- Should we not expect a real appreciation of Asian New Industrial Economies’ exchange rates relative to Japan to make a large contribution to the widening slack and structural depression in Japan?

- Is it helpful for Asian NIEs to use exchange rate policy to try and offset the sharply higher cyclical response of their export sectors to fluctuations in world industrial production? 1

- If various Asian economies—Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand—are becoming more vulnerable to speculative attacks, is it not appropriate to think of exchange rate regimes suitable for countries where macro instability predominates over trend growth influences?

- As Asia opens up to international capital flows, what is an exchange rate regime that goes with such a new and possibly dominant influence on the external balance and the financial sector?

- If US-Japan currency instability is a continuing feature, how should Asian NIEs respond, including the question of a yen bloc?

- How, if at all, does China figure in Asian NIEs’ exchange rate policy?

- With Europe moving towards a monetary area, with Latin America increasingly moving to the dollar, should Asia form a yen bloc?

Our discussion starts with a review of the situation, including broad policy options, and proceeds from there to policy recommendations. To anticipate our conclusions: no to a yen bloc because Japan is an unreliable anchor; yes to a Williamson-style band crawl which brings together the notion of an exchange rate regime or policy rather than haphazard, opportunistic exchange market actions. 2 The combined band+basket+crawl (or BBC for short) proposal offers, beyond sheer transparency, the desirable possibility of some (limited) flexibility of nominal rates (important from the perspective of asset markets) without sacrificing the predictability of real exchange rates (important matter for the goods market). Can it be done? Yes. Will it work perfectly? Probably not. Will it work better than other schemes? Yes. 3

1 The setting

We can think of exchange rate regimes almost as a continuum from full dollarization, at one extreme, to fully flexible rates (with some monetary rules) at the other. Arrangements in between include currency boards, fixed rates, strict crawling pegs, crawling pegs with bands, and dirty floating. If this variety is not enough, an extra dimension for these arrangements can be added, since they may be defined (other than by dollarization or currency boards) relative to a reference currency or basket. It would be surprising if there were a simple answer to what regime to use.

In fact, barring the extreme of dollarization, just about every arrangement is being used somewhere at the present time. This is not surprising in view of differences in the composition of trade, in the diversification of trade, and in the extent of macroeconomic stability. Because key currencies in the world move relative to each other—the DM/US dollar and the yen/US dollar rate—there are trade-offs between various considerations and, as a result, in different countries there are different optimum currency arrangements (see Table 1.1; see Appendix for exchange rate regimes in Asia).

There is yet a further dimension in which regimes differ: the extent and the details of currency convertibility. Here, the range is from restricted current account convertibility to full and unrestricted foreign exchange transactions for goods, services and assets. The striking evidence is that in these superperforming economies, even today currency convertibility is substantially restricted. Of course, across countries the extent of limitations differs substantially.

Table 1.1 Asian currency arrangements

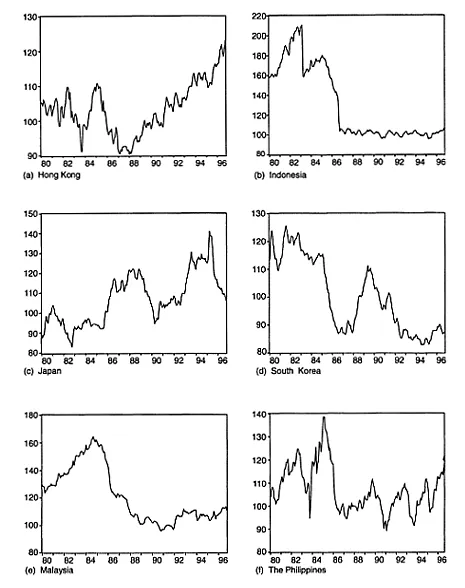

Figure 1.1 REERs of Asian Countries

Source:JPMorgan Internet web site.

Restrictions on the capital account predominate, but they are porous or entirely on the way out.

Whatever the nominal exchange rate regime, one important question is always the behaviour of the real effective exchange rate (REER). Figure 1.1 shows a sample of major East Asian economies using the data provided in JPMorgan’s web site. The sample period is 1980—July 1996, and the data refer to manufacturing. Interesting differences are immediately apparent; Hong Kong’s steady real appreciation, the wide fluctuations in the Japanese real exchange rate (deriving from the movements in the yen/US dollar rate) with a resulting impact on all Asian economies, and the stability of Indonesia’s real exchange rate since 1987. 4

The extent of the stability of real exchange rates is reported in Table 1.2. We show the coefficient of variation for each country, and for two sample periods. We also aggregate Asia (as a simple weighted average) and compare it to Latin America. The results are striking.

In the 1990s, real exchange rates are more stable in almost all Asian economies than they are for the longer sample period. In Asia, real exchange rates are consistently far more stable than they are in Latin America. This does not in and of itself imply that the Asian exchange rate policy is ‘better’. Asia’s greater stability may reflect the fact that there have been more shocks in Latin America and hence greater volatility in equilibrium relative prices. This is true, but it would be a mistake to dispense with common sense. Asia’s macro economy is more stable, and this is certainly partly due to a conscientious policy of stabilizing real exchange rates (around trend).

Table 1.2 Stability of REER (coefficient of variation, %)

The analysis of real exchange rate volatility is supplemented in Table 1.3 which presents correlations of the REER across Asian economies. The striking point is that there is substantial correlation. This is largely explained by exchange rate management that has one eye on the dollar and the other on the yen. But, clearly, the correlation is not complete, which suggests, reasonably, that different countries face different trade environments or pursue different targets and strategies.

Table 1.3 Correlations of REERs among Asian developing countries

Table 1.4 Trade patterns of Asian economies (%)

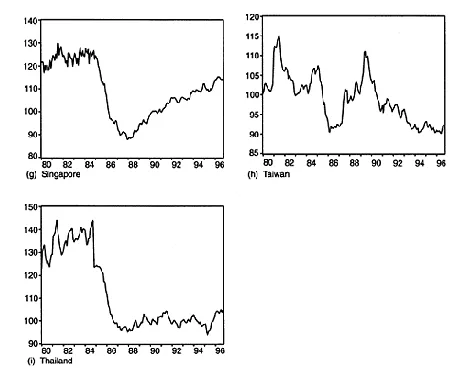

Figure 1.2 Shares of East Asian trade

Source:IMF, Direction of Trade Statistics, various issues.

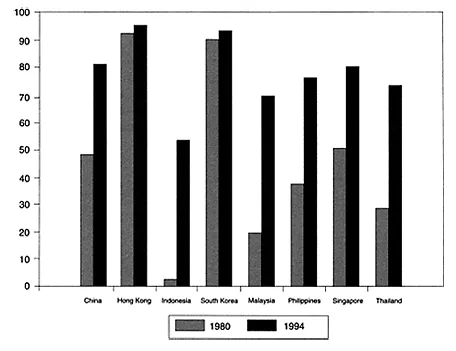

Two crucial aspects of East Asian economies are their very substantial exposure to trade and the extent of intra-Asian trade. These aspects are highlighted in Table 1.4. Figure 1.2 picks up the same facts by including Japan in the set of export destinations. The simple message is this: intra-regional trade is now half or more of the region’s total trade.

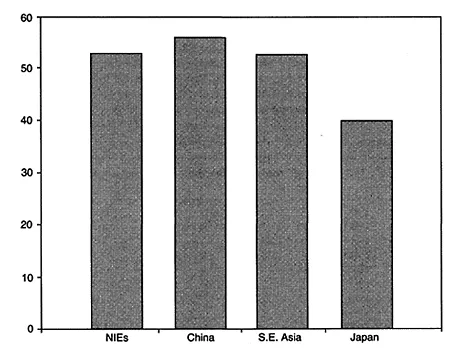

A final characteristic worth noting is trade structure. Over the past two decades, trade has increasingly shifted to manufactures. Countries which in the past were typical commodity exporters, say Indonesia or Malaysia, today show very substantial concentrations in manufactures as shown in Figure 1.3 and Table 1.5. For other countries such as South Korea, this was always the case.

The concentration on manufactures means two things. First, Asian economies are more nearly competitive with each other. Exchange rate policies that do not closely follow the same pattern have a major impact on the countries’ relative competitiveness. Second, exports should be highly cyclically correlated with the business cycle in advanced countries. This is more true, of course, the more Asian economies supply intermediate goods.

Figure 1.3 Manufactures exports (percentage of total exports)

Table 1.5 Manufactures exports (% of total exports)

A final preliminary concerns the impact of exchange rates on trade flows. Since the policy discussion on the exchange regime assumes that exchange rates do matter, we should offer support for that premise before moving any further. An important body of evidence on the adjustment of trade flows has been brought together in a paper by Reinhardt (1994). Reinhardt shows that for developing countries, in the aggregate and by region, trade flows are significantly responsive to relative prices. The same is true for the import elasticities of industrial countries in their trade with emerging economies, which is reported on the right-hand side of Table 1.6. Note, however, that the elasticities shown by other studies are far smaller than those usually found in industrial countries, although relative prices are found to be statistically significant in most of the developing countries.5 The reason for this finding still needs to be investigated, and there are not necessarily any grounds for pessimism about elasticity. Studies that focus on substitutability among alternative suppliers among emerging economies tend to find relatively high elasticities.

Table 1.6 Regional and aggregate import demand

Of course, showing that trade flows respond to relative prices is not enough to make the case for the effectiveness of exchange rate changes. It must also be shown that nominal exchange rate changes translate substantially into real exchange rate movements. That is very often not the case. The more inflationary the economy, and the more it is indexed, the less likely that a devaluation has lasting real effects. Of course, this applies more to Latin America than to Asia. The fact that developing economies are very open increases the difficulty of making a major real depreciation stick since it is so obviously a cut in real wages.

2 The convertibility issue

Exchange rate policy has two dimensions: the extent of convertibility and the specific institutional arrangements that determine the day-to-day setting of exchange rates. We start with the issue of convertibility and move from there to exchange rate regimes.

Asia, including Japan, has a history of procrastination in freeing up trade in assets and financial services. This reluctance to some extent reflects the high degree of financial repression prevalent in Asian financial markets, the absence of effective sterilization tools, and the poor quality of balance sheets in the aftermath of a long period of mismanaged finance. The good macroeconomic performance of Asia has a surprising and perhaps strange counterpart in the neglect of financial markets as opposed to forced savings mechanisms. Thus, the lack of an open capital account also reflects a supporting policy for domestic management of the macro economy. It also, of course, reflects a determination to capture domestic savings for domestic investment.

It might perhaps be claimed that restrictions on convertibility have worked in the past—that there was more investment and growth, and fewer disturbances were imported via the capital account. That view, of course, expresses the underlying sense that capital movements are mostly a nuisance. If countries with high domestic saving rates had accompanying high rates of efficient investment, that would not be altogether implausible. Of course, if saving is inadequate or investment is inefficient, there can be little support for closing the capital account to the market.

Even where a country can plausibly claim high saving and efficient investment, failure to implement the decentralization required for an open capital account becomes increasingly difficult to defend. If transition to an open market is accepted in principle, steps should be taken to put it into practice. An appropriate regulatory structure has to be established and pre-emptive clean-up operations in the balance sheets of existing institutions have to be carried out. There seems little reason to delay an inevitable process.

For example, although membership in the OECD carries a commitment to an open capital account, South Korea is finding it difficult to take the plunge. Is it then surprising that China, for example, is postponing far more rudimentary reform towards current account convertibility?

The overriding presumption is that an early move to full and unrestricted convertibility will mean having to deal with a multitude of remnants from the previous intensely managed, repressed economies. 6 The accumulating evidence on inefficiency of the investment process, including overinvestment, reinforces the presumption that a more decentralized structure of decision making (the greater choice and freedom that come with markets) is highly desirable. Of course, there is a need to deal with the resulting question of stability. With substantially full convertibility, market factors become a significant source or amplification of disturbances. Here, the exchange rate regime, including regulation, must come into play to make the move to the market on a net calculation a beneficial experience. Above all, in opening the capital account, work on cleaning up the banking system will have to be complete. As is well known, bad banks get worse over time. There is therefore no excuse in delaying this preliminary step. 7

3 Exchange rate choices: fixed rates

Just what to make of exchange rate policy depends on one’s prior experience as to how the economy operates. At one extreme is a monetarist-equilibrium view: wages and prices are fully flexible so as to clear markets. What is left is the determination of the level of prices, the rate of inflation, the exchange rate and the rate of depreciation. The realexchange rate is not a policy variable in any sense.

This is indeed a useful starting point because it highlights two issues: one is the inflation implication of the currency regime; the second is the question of trend changes in the real exchange rate. Both issues have an important bearing on the choice of exchange rate regime.

Consider first the question of the national rate of inflation. Under fixed rates, assuming purchasing power parity (PPP), the rate of inflation is determined by the rate of increase of import prices. It is thus determined substantially by the rate of price increase experienced by the dominan...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Editors’ Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- Part I: Exchange Rate Policies in Asia: The evidence

- Part II: Exchange Rates and Economic Development: Long-run views

- Part III: Regional Monetary Cooperation: Rationale and effects

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Exchange Rate Policies in Emerging Asian Countries by Stefan Collignon,Yung Chul Park,Jean Pisani-Ferry in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.