![]()

SIX

The International Development of the Korean Automobile Industry

Marc Lautier

INTRODUCTION

The South Korean automobile industry was simply not on the world manufacturing map in the 1970s. During the two following decades, however, it has grown extraordinarily rapidly. Between 1975 and 1996, its production increased by a factor of 75, from 37,000 units to over 2.8 million units. At the end of this period, South Korea was ranked 5th in the world automobile industry, with a 5.3 per cent share of global production, and automobile firms were planning massive new investments.

This successful development is unique in recent history. Over the last 50 years, no country other than South Korea has followed the Japanese path and fostered the emergence of indigenous automobile manufacturers1.

The Korean experience is also unique as far as internationalization is concerned. Economic theory has traditionally insisted on the role of firms’ competitive advantages in explaining foreign investment.2 Indeed, internationalization in the automobile industry has always been driven by firms’ ownership advantages, from the early foreign investments of GM and Ford in Europe and Japan, based on their lead in mass-production technology, to the more recent Japanese expansion abroad, based on ‘lean’ production methods. In the case of Korean manufacturers, however, the reverse causal sequence gives a better explanation of their internationalization process. Their recent foreign investment drive has been primarily motivated by the need to overcome competitive disadvantages. Indeed, the export expansion and the rise of foreign production in the 1990s have resulted from the firms need to catch up rapidly with their foreign competitors in terms of size. The Korean automobile industry has been engaged in a ‘capacity-push’ growth since the early 1980s, in which capacity expansion has always been ahead of the demand. This over-investment strategy aimed at drastically reducing catching-up time by accumulating faster learning and scale economies. Thus, the initially limited size of the domestic market, the fierce competition among Korean makers and the absolute necessity to increase volume to pay off huge investments forced them to export early on. In the mid 1990s, however, despite their remarkable growth Korean carmakers were still small compared with foreign mass-producers. At the time, Korean firms had not yet acquired a significant competitive advantage within the world oligopoly, in terms of product quality, productivity or technology. Accordingly, they had to keep on growing at a fast pace because volume expansion was the easiest way to catch up in terms of productivity and technology. But the domestic market ended its rapid climb, while the traditional export markets could not absorb the large additional volumes that Korean firms had planned to sell. However, the largest emerging markets — namely the ones with the greatest growth potential — remained almost untouched by export strategies, and firms realized that investing abroad had become the best way to speed up their expansion.

Since basic information on Korean firms’ strategies, especially abroad, has often been confusing, the first goal of this chapter is to evaluate the true scope of Korean carmakers’ foreign operations and to present their specificities in the late 1990s, before the industry restructuring. At a more theoretical level, the paper argues that competitiveness has been the goal rather than the source of Korean automobile firms’ foreign investment drive. Foreign direct investments are thus becoming an integral part of their catching-up strategy. Furthermore, Korean carmakers’ competitive position within the world oligopoly explains their location choices. Section I presents the stylized facts of the Korean automobile industry development and its main outcomes, underscoring the lack of economies of scale and of any specific competitive advantage within the industry. Section II describes how Korean firms have stepped up their exports and diversified into foreign markets. Section III provides key figures of their foreign involvement and an analysis of outward direct investment (ODI) location and implementation strategies for Korean carmakers.

CATCHING UP IN A MASS PRODUCTION INDUSTRY

The development of an automobile firm requires adequate technological skills, a market large enough to exploit economies of scale and an efficient network of component suppliers. In leading countries these different components of the ‘automobile system’ have grown in parallel, whereas the Korean strategy has been characterized by unbalanced development. As a result, Korean carmakers have been able to grow faster, but their competitiveness and technological base have remained fragile.

The capacity-push strategy of the Korean automobile industry

Like many modern East Asian industries, the Korean automobile industry was built without initial comparative advantages. Korean firms had no technology, no capital and no supporting industry. Even demand was lacking, since the Korean automobile market stayed far below 100,000 units until the early 1980s. The main features of its successful development have been the aggressive investment strategy backed by strong support from the government and the use of strategic short-cuts to reduce the catching-up period.

State’s support and strategic short-cuts

For the past three decades, the automobile industry has been regarded as a major strategic industry in Korea. During this period, the Korean government has promoted the industry through different means, including preferential credit allocations, protection of the domestic market and export incentives. It has also implemented regulating policies and restructuring measures. The main objective was to achieve economies of scale rapidly which, combined with relatively low wages, could give Korean carmakers a competitive advantage despite their lack of manufacturing experience and technology. However, industrial policy has always favored several firms in the sector in order to stimulate efficiency and limit market power. These sometimes incompatible policy goals explain the succession of rationalization measures (to allow firms to attain a critical size) and liberalization measures (to develop competition).

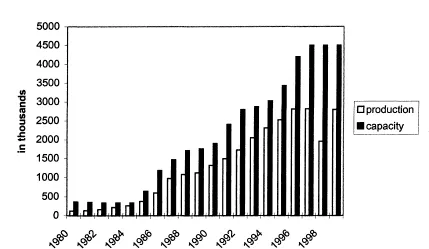

The firms’ aggressive investment strategies, combined with the flow of State-controlled bank financing, have locked the automobile industry into a ‘capacity-push’ growth since the early 1980s.3 Although production increased by a factor of 23 between 1980 and 1996, capacity expansion has always been one step ahead. Korean manufacturers have created the potential for the third or fourth largest industry in the world. Despite a worldwide automobile over-capacity estimated at 30 per cent, Daewoo inaugurated a new USD 1.2 billion plant in Kunsan in April 1997, with an annual capacity of 320 000 units. At the time, the three main carmakers were planning on a production capacity of 7 million units by the year 2000, betting on growth in such developing markets as China, Indonesia and Russia.

Figure 6.1 Production and capacity

Source: KAMA

The most impressive characteristic of Korean automobile industry development has undoubtedly been its fast-paced growth, made possible by three strategic short-cuts: intense technology transfers from advanced producers, early export orientation to tap foreign demand, and a bias towards in-house production of components.

Already back in 1974, Kia embarked on the production under license of a Mazda vehicle, Saehan (formerly Daewoo Motor) launched a similar cooperation scheme with Isuzu, while Hyundai tried to open the ‘technological package’ by contracting with different technology suppliers. To build a ‘national car’, the Pony, Hyundai used an Italian design (Ital design), core components from Japan (Mitsubishi) and English engineers (from British-Leyland). Later on, increasing strategic autonomy in the context of structural dependence on foreign technology became a major objective. In terms of strategy, Hyundai has stressed self-reliance the most. The company failed to complete joint venture negotiations with Ford in 1972 and with GM in 1981 notably because Hyundai did not want to lose managerial control and limit its access to export markets.4 It has relied heavily on technology licensing to develop its model range and manufacturing process.5 Mitsubishi Motors soon became its main technological partner, but Hyundai managed to avoid an exclusive partnership and diversified its technology sources (see Appendix 6.A1). In contrast, Daewoo Motor initially operated within the framework of General Motor’s global strategy, following a joint venture agreement. Technology transfers from GM and its affiliates allowed Daewoo Motor to enter the mass production stage without developing its own technology. But the GM-Daewoo partnership became shaky in the 1980s and ended up in 1992 with GM disengaging. However, the GM group has remained an important technology supplier for Daewoo.6 Despite their late entry and small size, Korean firms have been particularly successful in turning their initially unbalanced relationships with leading MNEs to their advantage. By blocking any direct access to the Korean market, the State has reinforced the bargaining power of local firms.

Initially the domestic market was unable to absorb large volumes of cars. Thus Korean firms’ rapid growth strategies implied the development of foreign sales. Various governmental incentives have guided them along the export route at an early stage.7 Prior to 1984, there were almost no exports — a total of less than 150,000 cars had been exported, mainly to less industrialized countries (South-East Asia, Middle East). By 1988, however, exports, aimed almost exclusively at the North American markets, had surged to a peak of 576,000 units. As it is well known, Korean exports nose-dived, declining by almost 40 per cent in the next two years.

However, the rapid growth of the Korean industry has continued unabated, despite the pessimism of many analysts.8 This is primarily due to the take off of the domestic market, whose explosive growth has more than offset the decline in exports (see Figure 6.2). Indeed, the partial withdrawal from North-America ensured an adequate supply for Korean salarymen, impatient to enter the mass consumption stage.9 Yet the domestic market has been rapidly maturing and exports are once again increasingly the driving force behind the sector.

In Korea, vertical integration has been used extensively to reach a high local content ratio early on and to accelerate the development of a complete manufacturing base. The industrial concentration process of the 1970s weakened small- and medium-sized businesses. Once they entered the mass production stage, Korean carmakers invested heavily in their own parts and components facilities. Furthermore, imported components were necessary to meet quality standards on export markets.10 This preference for in-house productions and imports reduced the available market for independent components firms, hence their growth and development.11 The carmakers’ internalization ratio has remained high by world standards, around 50 per cent in the early 1990s (Chung, 1994; Lautier, 1993). As a result, the industry’s growth and tec...