![]()

1 Food for fuel or fuel for food?

The impact of biofuel production on the interactions between crude oil and food prices

Introduction

Fuel and food markets are traditionally linked because agricultural production requires energy as input for irrigation, transportation, mechanization and fertilization. However, recent biofuel production establishes a new channel between the two sectors: some agricultural commodities are increasingly used to produce fuel rather than food. This chapter adopts time-series techniques to analyse how biofuel production influences the relation between crude oil and agricultural prices, distinguishing the effect of crude oil as an input from the effect of biofuels.

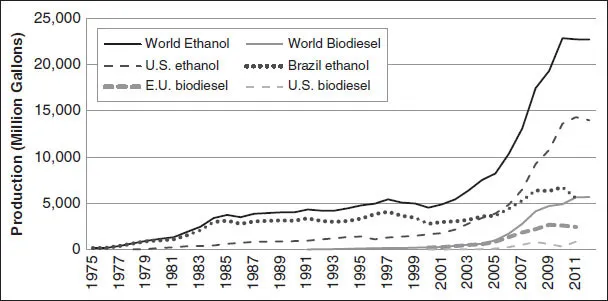

Biofuels are a very recent issue, because the world’s biofuel production has increased more than fourfold since 2000. As Figure 1.1 shows, global ethanol production expanded from around 5,000 million gallons in 2002 to almost 23,000 million in 2012, mainly because of the rise in US corn-based ethanol production. Meanwhile, biodiesel production increased more than tenfold, from less than 400 million gallons in 2002 to more than 5,500 in 2012 (Brown 2012). The rise in biofuel production has been driven by energy policies set by the governments of many developed economies, such as the USA and EU, aiming at strengthening their energy independence and reducing GHG emissions.

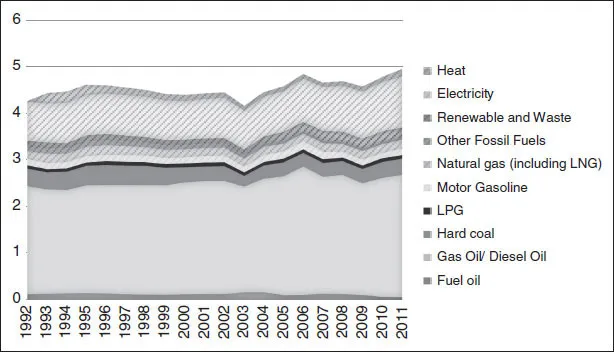

In recent years, biofuel policies may therefore have contributed to reinforce the tension between the energy and food sectors, raised by high energy prices, which contributed to an increase in food prices. As Figure 1.2 shows, fossil fuels are the main source of energy consumed in agriculture, and fuel prices traditionally are an important component of production costs, influencing the costs of fertilizers, mechanization, irrigation and transport (Alexandratos 2008). For this reason, crude oil prices are influencing the production cost of agricultural commodities. Despite a quite stable use of energy in the agricultural sector, the cost of fuel, fertilizers and pesticides has begun to increase since 2004 (Trostle 2008). For instance, the US dollar price of some fertilizers increased by more than 160 per cent in a 1-year period starting in the first 2 months of 2007 (FAO 2008b); while freight rates also doubled in February 2006, compared with the same period in 2005 (FAO 2008b), due to an increase in crude oil prices.

Figure 1.1 World’s biofuel production, 1975–2011.

Source: Author’s elaboration on the dataset of Lester R. Brown, Full planet, empty plates: the new geopolitics of food scarcity. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2012, with Earth Policy Institute: www.earth-policy.org.

Figure 1.2 Consumption of energy in agriculture, forestry and fishing per unit of arable land and permanent crops (gigajoules per hectare), 1992–2011.

Source: Author’s elaboration based upon UN data, accessed 25 February 2015.

In the 2007–2008 period, high fuel prices induced a sharp increase in food prices, pushing millions of people into hunger and generating uprisings and protests in many developing areas. Despite a decrease due to the global crisis in 2009 and recent low levels in 2015, high international prices produce problems for poor food-net-consumer people. A general increase in food prices exacerbates world hunger, because it reduces the availability of cheap food and leaves poor people unable to adjust their pattern of consumption by replacing a more expensive staple with a cheaper one. For instance, a 1 per cent increase in the average prices of all major food staples may almost halve the caloric consumption of the world’s poor (Runge and Senauer 2007). In fact, if the prices of many staples increase simultaneously, poor people are not able to substitute an expensive good with a cheaper alternative in order to maintain a similar calorie intake, therefore they find themselves in a much more vulnerable situation in terms of food security.

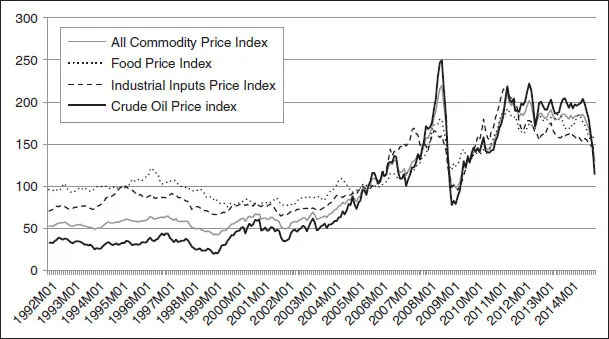

Figure 1.3 Oil, food, industrial and all-commodity price index, 1992–2015.

Source: Author’s elaboration on IMF data, downloaded 06 February 2015.

Notes: All Commodity Price Index, 2005 = 100, includes both Fuel and Non-Fuel Price Indices; Food Price Index, 2005 = 100, includes Cereal, Vegetable Oils, Meat, Seafood, Sugar, Bananas, and Oranges Price Indices; Industrial Inputs Price Index, 2005 = 100, includes Agricultural Raw Materials and Metals Price Indices; Crude Oil (petroleum), Price index, 2005 = 100, simple average of three spot prices: Dated Brent, West Texas Intermediate, and the Dubai Fateh.

As Figure 1.3 shows, the price of crude oil increased sharply from 2007, more than doubling in less than 2 years, then decreased in 2009 due to the global recession, but it has been at a high level since then, despite a decrease in 2015. The picture suggests also that, especially from 2005, the price of crude oil seems to be driving the trends in the price index of food and all the other commodities. This is less evident for the index price of industrial commodities, which is less related to the price of crude oil.

The increasing correlation between crude oil and food prices is partly due to the growing production of biofuels in the twenty-first century. The enlarged demand for feedstocks used to produce biofuels affects also the prices of other crops not directly involved in bioenergy productions. In fact, the growth in biofuel production has contributed to an increase not only in the prices of the commodities used in the sector (mainly maize, oilseeds and sugar), but also on the prices of apparently unrelated crops and commodities (Runge and Senauer 2007). This has been due to the displacement of land from non-bioenergy agricultural products to bioenergy ones, which in turn reduces their supply and increases their prices. Soybean acreage in the USA is an emblematic example of displacement effect. Soybeans were normally produced in rotation with maize on the same land, but given the strong demand for corn for ethanol production, soybean acreages were switched to produce maize, and the price of soybeans increased. Between 2006 and 2008, the number of soybean acres decreased by about 11 million, while the corn acres augmented by about 15 million (Congressional Budget Office 2009).

As we will see in Chapter 3 and 4, the process of land conversion is often connected with environmental issues such as soil erosion, nitrogen runoff, lower biodiversity and a high water footprint (Runge and Senauer 2007). Policies incentivizing biofuel production were adopted with the aim of reducing GHG emissions, but many recent analyses show that, taking into consideration the biofuel entire productive chain, the reduction of GHG emissions through the production of biofuels is not significant (Graham-Rowe 2011). While net emissions from burning biofuels are lower than those from gasoline combustion, planting, fertilizing, watering and harvesting biofuel feedstocks often requires more fossil-fuel energy than does producing gasoline from petroleum (Congressional Budget Office 2009; FAO 2008a). So, biofuels have played a very important role in increasing the demand for food commodities and therefore their prices, having a direct and a substitution effect on the production of a great number of crops. For instance, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO 2009) estimates that in the USA domestic ethanol production increased the price of corn by 50–80 cents per bushel between April 2007 and April 2008.

This chapter further expands on the topic of the implications of biofuels on agricultural prices at a global level, being one of the first attempts to link together fuel and food sector in order to identify the role of biofuel on price transmission between the two sectors. To the best of my knowledge, this is the only work separating the input and the biofuel channel, as well as testing for structural breaks in the global prices relationship. Biofuel is a recent topic and affect consumers worldwide, despite the concentration of biofuel production in a few countries. For these reasons, the chapter analyses recent data for the longest period available (1980–2014), and uses price data at the world level.

Assessing the impact of biofuel production on the oil–food relationship has obviously important policy implications, since this production is highly subsidized and incentivized. For instance, the G8 meeting in L’Aquila in 2008 provided funds for increasing agricultural productivity in order to enhance food security, but most of this money went to boost the production of biofuels, which may instead threaten it by raising food prices.

Other factors such as mechanization of agriculture practices or financialization of commodity markets may have contributed to induce a further link between food and fuel prices, and I control for this in the analysis. Still, if biofuels strengthen the link between crude oil prices and agricultural prices, in the presence of high prices, biofuel incentives and targets need to be questioned in order to not jeopardize food security. Mandatory quantities of bioenergy and subsidies to producers incentivize the production of biofuels, despite the fact that it may divert many feedstocks from food use to fuel, and increase food prices.

This chapter is organized as follows: the Literature review section assesses how the literature has addressed the interactions between fuel and food prices in order to explain the price transmission mechanisms that will be investigated with time-series analysis. The section following the literature review explains in detail the data and the methodology used. The Empirical analysis and results section analyses the empirical cointegration between crude oil and agricultural commodity prices with and without the effect of biofuel production, and presents the results obtained by the stationarity test, the Johansen cointegration analysis and the Granger causality test. Finally, our estimates help us draw overall conclusions, presented in the final section.

Literature review

Fuel and food sectors are linked together by two main channels: first, crude oil is an important input in agricultural production; furthermore, biofuels establish a second significant tie in this relationship. The food and fuel debate and the economic consequences of biofuels have been analysed in the literature by means of partial and general equilibrium models, as well as by time-series techniques and other kinds of analysis (Serra and Zilberman 2013; Zilberman et al. 2012). Computable general equilibrium (CGE) models (Hertel et al. 2008; IFPRI 2010; Saunders et al. 2009) and partial equilibrium (PE) models (Abbott 2012; Ciaian and Kancs 2011; Elobeid and Tokgoz 2008; Gardner 2007; Ignaciuk at al. 2006; Rosegrant et al. 2008; Tyner 2010) have been criticized for assuming arbitrary price transmission elasticity and performing poorly. Moreover, such mathematical programming models are calibrated on a particular year dataset, and therefore are unable to catch time trend and variation. Hence this chapter relies on a time-series approach.

As Table 1.1 shows, several studies have analysed the food–fuel relation using time-series econometric techniques. Table 1.1 summarizes some recent contributions which address the correlation between fuel and food, mainly adopting the vector autoregression (VAR) structure. The papers addressing this issue differ in terms of countries, commodities and methodologies used. Some of the studies have a national focus, in particular Armah et al. (2009) and Baek and Koo (2010) focus on the US market; Ahsan et al. (2012) analyse Pakistan’s food prices; while Imai et al. (2008) concentrate particularly on China and India. Moreover, several papers consider energy prices and/or biofuels as one factor among many affecting food prices, or do not consider biofuels at all, as in Ahsan et al. (2012). Furthermore, different food commodities are selected as dependent variables, almost always through inexplicit criteria. Finally, the authors adopt different techniques to analyse the price relationship, such as the: autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model; ‘lead/lag’ causality model; multivariate generalized autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity (GARCH) model; s...