- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fixing Financial Crises in the 21st Century

About this book

Financial crises have dogged the international monetary system over recent years. They have impoverished millions of people around the world, especially within developing countries. And they have called into question the very process of globalization. Yet there remains no intellectual consensus on how best to avert such crises, much less resolve th

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Introduction

1 Fixing financial crises in the twenty-first century

Andrew G. Haldane

1.1 International financial crises – past, present and future

International financial crises have been with us for as long as international financial markets. On some measures, however, the incidence of international financial crises increased in the last part of the twentieth century. Caprio and Klingebiel (1996) document 112 crises in 93 developed and emerging economies since the late 1970s.

Table 1.1 lists some of the systemic financial crises to have hit emerging market economies (EMEs) since the Mexican crisis in 1994/1995; it also shows the headline loan packages announced by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to help resolve these crises. Crises have struck all parts of the emerging market world. Unlike lightning, they have sometimes struck twice. Argentina recently suffered the first systemic international financial crisis of the twenty-first century. Doubtless, it will not be the last. History, especially recent history, suggests that financial crises may have become part and parcel of the international financial landscape.

But it is not just the incidence of financial crises that has altered in recent years. So too has their nature. And as the nature of crisis has changed, the difficulty of resolving them has also escalated. For example, consider the evolution in the role of the IMF in resolving financial crises since its inception. The IMF was put in place after the Second World War to help redress current account imbalances among its member countries. That role persisted through until the 1970s and 1980s. Up until that point, financial crises were typically rooted in an inability of member countries to finance current account deficits, themselves often the result of fiscal or monetary policy profligacy by the official sector.

Table 1.1 Recent systemic emerging market crises

The 1990s, however, saw a sea-change. Capital account liberalisation in a number of EMEs exposed them, as never before, to the vicissitudes of international capital markets. Footloose international flows of funds magnified vulnerabilities and imbalances in the capital account, as well as the current account, of the balance of payments. The crises in Mexico in 1994/1995, across South-East Asia in 1997, Russia in 1998, Brazil in 1999 and 2002, and Turkey and Argentina between 2000–2002 were all sourced in the external capital account. We appear to have entered an era of capital account crisis (IMF 2002).

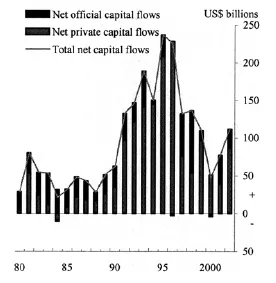

This new strain of crisis carries important implications for policymakers. Capital account crises appear, if anything, to be even more virulent and costly than their current account cousins (Bordo et al. 2001). They involve stock adjustments in balance sheet positions, rather than flow adjustments in the balance of payments. This helps account for the greater depth and severity of capital account crises. It also helps account for their virulence. For stocks of capital can reverse direction at speed, as well as in size. According to the Institute for International Finance (IIF), capital flows to EMEs reached a high-water mark of almost $350 billion in 1996. In 2002, they stood at less than half that amount and are forecast to remain at these depressed levels for the next few years (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Capital flows to emerging markets (source: IMF World Economic Outlook).

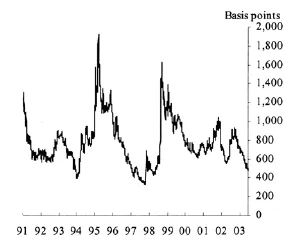

Figure 1.2 EMBI and EMBI global spread compositea (source: JP Morgan Chase & Co.).

Note

a EMBI index until 30 December 1997, EMBI global from then until present.

This volatility in the quantity of capital flowing to EMEs is also mirrored in its cost. Figure 1.2 plots the average cost of borrowing by EMEs, measured as a spread over “safe” United States Treasury bond yields. The volatility in this cost of capital is striking. For example, the Russian crisis in August 1998 caused the spread to rise by a factor of three, from around 500–600 basis points to over 1,600 basis points.

1.2 Resolving international financial crises – past, present and future

Explaining crises, ex post, is one matter. Devising policy plans to resolve these crises, ex ante, is quite another. Since the Mexican crisis, considerable policy effort has been put into the handling of international financial crises. This effort is often described under the ambitious umbrella heading of “Redesigning the International Financial Architecture”. Some would see the initiatives currently on the table as somewhat less ambitious – more akin to plumbing and bricklaying than to architectural design (King 1999). But however described, the substantive public policy question is how we deal with crises that are more frequent, faster and more costly than in the past – that is, twenty-first-century capital account crises.

Broadly speaking, the official sector has pursued a two-pronged approach. A series of initiatives have been embarked on in an attempt to head-off crises before they strike – so-called “crisis prevention” measures. These are many and various (see, for example, Eichengreen 2002; Roubini and Setser 2003). But if one lesson has been learned above all others from recent crises it is that macro-prudential fault-lines are just as likely to cause a financial earthquake as macro-economic ones.

Recent crises have been rooted in the excessive accumulation of short-term debt, fragile banking systems, over-exposed corporate sectors and unstable sovereign debt dynamics, just as much as monetary and fiscal policy mishaps. If financial liberalisation continues apace, we would expect this pattern to increase with time. In other words, financial imbalances may take on an increasingly prominent role in instigating and propagating financial crises.

In response, a large number of so-called standards and codes have been drawn up, setting out best practices in various fields of macro-economic and macro-prudential policy. These include efforts to improve the transparency of macro-economic (monetary and fiscal) policies. But, just as importantly, they include efforts to improve countries’ macro-prudential policies – for example, efforts to ensure best practices in the financial regulatory and supervisory fields (for banks, insurance companies and securities houses); and measures to improve data, accounting and corporate governance (see Clark and Drage 2000).

The IMF, working alongside other international agencies, has been in the vanguard in assessing countries’ compliance with these best practice codes and standards. Specifically, the IMF’s Reports on the Observance of Standards and Codes (ROSCs) and the Joint IMF/World Bank Financial Sector Assessment Programmes (FSAPs) aim to provide a health check on countries’ macro-economic and macro-prudential vulnerability. By the end of 2002, 343 ROSCs had been produced for 89 countries and 45 countries had completed FSAPs. Another 25 are in progress and a further 27 scheduled. Though there is further to go, progress has been tangible.

The fruits of this labour have been difficult to detect in the data. In a way that is inevitable, for we have no clean counterfactual telling us how crisis-prone countries would have been had they not undergone these health checks. Moreover, it is fanciful to think that crisis-detection could ever be so accurate as to remove entirely the potential for crisis. Indeed, to do so would probably be undesirable, as it would signal an over-zealous approach to international financial regulation. Nevertheless, there are some tentative indications that these attempts at greater transparency, and the accompanying acknowledgement of macro-vulnerabilities, may be beginning to pay dividends.

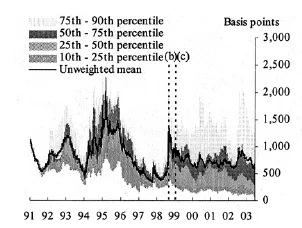

One straw in the wind comes from looking at the degree of dispersion in emerging market borrowing costs (Figure 1.3). These spreads were tightly compressed in the run-up to the Asian and Russian crises in 1997–1998. Currently, however, there appears to be a much greater degree of risk differentiation by the financial markets. Crisis prevention initiatives may have played some part in this encouraging development. Increasingly, too, it appears that rating agencies and other private sector bodies may be factoring crisis prevention initiatives, such as standards and codes, into their pricing decisions.

Figure 1.3 EME sovereign US$ bond spreads: distribution over timea (sources: JP Morgan Chase & Co. and Bank calculations).

Notes

a Unweighted cross-country distribution across components of the EMBI global index.

b Russian crisis – 17/8/98.

c Brazilian devaluation – 13/1/99.

The other strand of architecture initiatives has focused not on crisis prevention, but on “crisis resolution” – that is, mitigating the costs of crisis after they have struck. As with crisis prevention, there have been intense efforts by the official sector to make progress on this front, especially over recent years. And, as on the prevention side, these initiatives have been many and varied. Unlike on the crisis prevention side, however, progress has been rather less tangible. Why is this?

The short answer is – economics. Surveying the debate so far, there appear to be some fundamental analytical differences in people’s preferred approach to tackling crises. These analytical differences are the motivating force behind, and the common thread running through, the remainder of this book. Overlaying these analytical differences are of course the usual panoply of other factors – politics (national and international), vested interests, institutional inertia, etc. But the focus of the remaining chapters is on the economics of the crisis resolution debate, retrospectively and prospectively. The chapters aim to track the evolution of the debate up to the present day, highlighting the key economic themes, issues and initiatives. And they attempt to provide a glimpse into where we might be headed next on the international financial architecture project.

We begin, however, with an overarching chapter by Sir Edward George (former Governor of the Bank of England) assessing progress so far on both the crisis prevention and crisis resolution strands of the debate. It surveys the landscape of recent architecture initiatives and so sets the scene for the detailed synopses of particular themes and issues that follow.

1.3 Why involve the private sector?

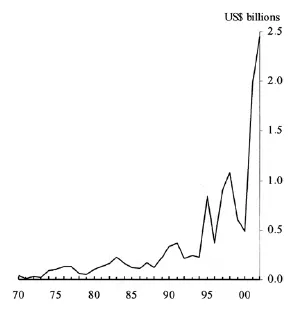

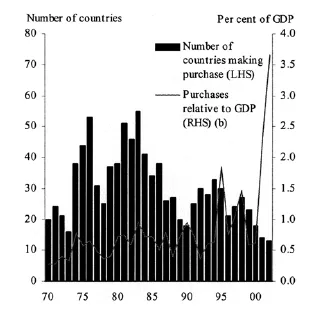

The IMF has played a pivotal role in the resolution of capital account crises. Recent IMF loan packages have ranged anywhere between $3 billion and $30 billion. The average size of IMF loans to all countries has risen from around $200 million during the 1980s, to over $2 billion entering the twenty-first century (Figure 1.4). By any historical metric, such as nominal GDP, the scale of IMF financing has dwarfed that in the past. And at the same time as the average size of loans has risen, the number of countries receiving them has fallen (Figure 1.5).

Large-scale official sector lending in response to financial crises has, of course, a long and distinguished intellectual pedigree, at least domestically. Bagehot (1873) first described the principles that should underpin such “last-resort” lending by a central bank to a domestic financial institution. These included that such lending should occur freely – indeed, in potentially unlimited amounts – against good collateral and at a penalty rate. Some have argued that there is a direct read-across to the management of international financial crises. Fischer (1999), in particular, proposes that the IMF could be turned into an international lender of last resort, furnishing an elastic supply of hard currency to countries in crisis. Indeed, based on past experience, it could be argued that the IMF has already played such a role, at least to some degree.

Figure 1.4 Average IMF loansa (sources: Gai and Taylor 2003 and IMF).

Note

a Average annual purchase from GRA (General Resources Account, excluding reserve tranche purchases) of those IMF member countries making a purchase in a given year.

Figure 1.5 Number and size of IMF loansa (source: Gai and Taylor 2003, IMF and IMF World Economic Outlook).

Notes

a Purchase from GRA (excluding tranche purchases). Sample is those member countries for which purchase and GDP data are available.

b Sum of purchases of IMF member countries making a purchase in given year relative to their total GDP.

This approach has come up against stiff opposition. One obvious constraint is a practical one: could IMF resources keep pace with the mounting scale of international capital flows? Even a cursory glance at the numbers suggests that IMF resources have not, and most probably could not, do so. Between 1970 and 1996, IMF quotas rose by a factor of less than two in real terms. Over the same period, world trade volumes rose by a factor of over four and real private capital flows by a factor of over eight. Capital flows have outpaced the growth in IMF resources by a factor of four to one.

Put another way, the current usable resources of the IMF are less than $0.2 trillion. That compares with a stock of emerging market debt well in excess of $2 trillion. If we were to add in domestic capital flight, the stock of assets that might potentially flee EMEs could easily be double that amount. So however the cake is cut, it seems most unlikely that the IMF could ever be resourced on such a scale that it could serve as a credible, and potentially unlimited, last-resort lender.

But there are also behavioural grounds for questioning the logic of last-resort lending. One role of public policy is to guard against distortions to risk-taking incentives – so-called moral hazard. Liquidity intervention in financial crises may potentially fall foul of that critique. Specifically, it may encourage excessive risk-taking, either on the part of the debtor (“debtor moral hazard”) and/or private creditors (“creditor moral hazard”). In assessing the efficacy of public policy intervention, these moral hazard costs need to be weighed against the benefits of liquidity provision.

Part 2 of the book considers such a cost–benefit evaluation. Michael Mussa (Institute for International Economics and formerly Chief Economist at the IMF) critically examines the empirical and conceptual evidence on the degree of moral hazard potentially induced by large-scale IMF loans. Mussa argues that much of the focus on international moral hazard may be misplaced, as the distorting effects of IMF loans are likely to be quantitatively unimportant provided the IMF acts in accordance with its Articles of Agreement. Why? Because the IMF offers loans to countries rather than grants. Moreover, historically at least, these loans have almost always been repaid in full. So the subsidy to countries and their creditors implied by IMF intervention is unlikely to be large enough quantitatively to have adversely affected debtor and creditor risk choices. Certainly, such a potential pecuniary gain is likely to be dwarfed by the pecuniary losses the debtor and its creditors face as a result of crisis.

William Cline (Institute for International Economics and formerly Chief Economist at the IIF) reaches a similar conclusion from a slightly different direction. If official lending is constrained, then the burden of adjustment following a crisis must instead be borne by private creditors – there will be so-called private sector involvement (PSI) in crisis resolution. Some degree of PSI, Cline argues, is of course desirable. Private investors should bear the consequences of their risk choices. But the watchword of official sector PSI policy should be “voluntary”. Involuntary attempts to inflict losses on private creditors carry large deadweight costs for the debtor, in the form of insolvent banking systems, a slow return of private capital, etc. These costs dwarf the costs of IMF-induced moral hazard. So, based on a cost–benefit calculus, Cline argues, the IMF should always err on the side of official sector lending when resolving crises, rather than impose solutions on private sector creditors.

This view of the competing arguments is by no means unchallenged. First, as Mussa describes in his chapter, recent years may have seen the emergence of a new type of moral hazard – what he calls “geopolitical” moral hazard. The official sector may seek to bail-out countries for strategic rather than economic reasons, using the IMF as a conduit. Mussa believes this risk to be a real one, which has risen over recent years.

Second, some of the empirical evidence on moral hazard reaches a less sanguine view on its potential importance (see, for example, Haldane and Taylor 2003). International bail-outs have, on occasions in the past, depressed borrowing spreads (Dell’Arricia et al. 2002). They have also helped deliver excess returns to international creditors, over and above that which can be explained by reductions in the likelihood of crisis (Haldane and Scheibe 2003). And as the international safety-net has expanded, there is some evidence that debtor countries may have become less vigilant in addressing incipient vulnerabilities (Gai and Taylor 2003). All of these stylised facts are consistent with a degree of moral hazard having been induced by large-scale IMF lending. So, empirically at least, the jury remains out on the moral hazard question.

Third, as John Murray (Bank of Canada) describes in his commentary on Mussa, the case for restraint in official sector lending policies does not stand or fall on moral hazard. The case can equally be made on uncertainty grounds. Unpredictability about the lending response of the official sector may inhibit accurate risk-pricing by the private sector and may stymie policy risk-management by debtor countries. Against this backdrop, Murray makes the case for stricter limits on access to official financing. Access limits would serve as self-denying ordinance for the official sector, curbing the potential for discretion in official sector lending policy to disrupt the international financial system (Haldane and Kruger 2001; Council on Foreign Relations 1999).

The international community has recently taken to heart this desire for greater discipline in official lending policies. In April 2002, the Group of Seven (G7) countries committed themselves to strengthening IMF access policy. And in September 2002, the IMF’s Executive Board agreed new criteria and procedures to accompany any decision to grant access to IMF resources above normal lending limits (of 100 per cent of a country’s quota annually and 300 per cent of quota cumulatively).

These are steps along the road to establish...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Preface

- Part I: Introduction

- Part II: Why involve the private sector?

- Part III: How to involve the private sector?

- Part IV: Contractual resolution of financial crises

- Part V: Statutory resolution of financial crises

- Part VI: The road ahead

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Fixing Financial Crises in the 21st Century by Andrew Haldane in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.