1 Introduction

Instances in which attacks from the opposition are met by violent attacks from the state, or examples of civil society protesting against a repressive government, can be found from all around the globe. President Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe has increasingly used repression, torture and political imprisonment to silence his opponents and to intimidate potential protesters against his regime; any calls for strikes by the main opposition party are immediately silenced by security forces. In 2002, a major strike organized by labour unions, industrial magnates and oil workers in Venezuela against President Chavez, resulted in the firing of the management of the state-run petroleum company and the dismissal of thousands of its employees, but overall comparatively limited violence was used to end this form of dissent. In Tibet during March 2008, Buddhist monks demonstrated peacefully against religious restrictions by Chinese authorities. Chinese security forces arrested large numbers of the protesters, which further escalated the display of dissent. This, in turn, led to the escalation of violence between the Tibetan protesters and Chinese police.

Looking at these conflicts, several questions arise. How do governments respond to popular protest? When do governments respond with violence to their citizens protesting, particularly when this protest is peaceful? How does a violent government crackdown influence the dynamics of the protest? Does government repression increase protest and the risk of rebellions? Is the interaction between the government and the opposition different under different political regimes? These are the main questions addressed in this book. It investigates the relationship between protest and repression in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa.

The question whether domestic protest leads to repressive or cooperative behaviour of the government and its security forces is important not only for the dissidents and protesters themselves, but also for national and international actors who try to mediate conflicts between the government and the opposition. If domestic protest triggers state cooperation, then the display of discontent is no reason for severe concerns about its consequences. However, if the display of opposition leads to a tighter grip by the government on actual and potential opponents, then steps to intervene and mediate the situation should be taken at the first signs of domestic dissent. For example, prior, during and after the general elections in Zimbabwe in March 2008, students and members of the opposition party Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) staged various protests and rallies against President Mugabe. The response of the government, however, was clear: it intimidated opposition supporters with the use of widespread violence, further limited the freedom of the press and generally tightened its grip on power. The question is whether these immediate retaliatory actions are a typical pattern of state–societal relations and whether the dynamics of these interactions differ under different circumstances.

This book analyses the relationship between domestic protest and state repression in Africa and Latin America between the late 1970s and the beginning of the twenty-first century. It sheds light on how domestic dissent and state coercion respond to each other. The main question addressed in this book is whether domestic protest triggers state coercion and whether state coercion triggers domestic protest. It empirically analyses whether the dynamics of domestic conflict differ between democracies, semi-democracies and non-democracies, and whether there are geographically distinct patterns of interaction by comparing countries from sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America.

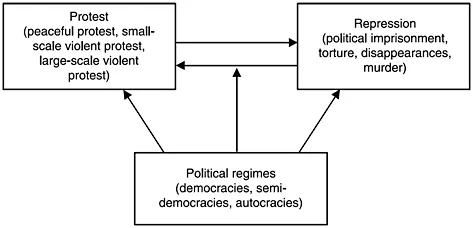

Figure 1.1 graphically displays the relationships that are the focus of this book. I investigate how dissent influences repression, and how state coercion impacts upon actions of dissent. Particular attention is paid to how, if at all, the nature of this protest–repression nexus differs under different political regimes, focusing on the degree of democracy as the core characteristic. Finally, I investigate how the degree of democracy influences the use of violence by governments and the protest behaviour of the population. To explore the relationships shown graphically in Figure 1.1 from different angles, I use a mixed-method form of analysis, employing quantitative and qualitative methods. The initial analysis is conducted at the macro level.

Figure 1.1 A model of protest, repression and political regimes.

It employs ordered probit models to analyse yearly data from 66 Latin American and sub-Saharan African countries between 1977 and 2002. The analysis differentiates between different types of dissent (peaceful dissent, riots and large-scale violent dissent) and different degrees of repression. It demonstrates how these types of protest affect repression, and how repression influences protest. The analyses also examine the impact of regime type on both protest and repression, controlling for political instability, civil war, population size and regional differences between Latin America and Africa. These general analyses are complemented with a series of individual time-series analyses with daily data from six Latin American and three African countries. The main contribution of this second set of statistical analyses is that it specifically models the reciprocal dynamics between protest and repression. It extends the definition of these two concepts to include verbal behaviour and incorporates accommodating actions into the analysis of domestic conflict. These two quantitative approaches are complemented by two case studies, of Chile and Nigeria. They provide a historical narrative to the protest–repression nexus, and add a further, in-depth dimension to the picture that is outlined by the statistical analyses.

In the remainder of this chapter, I present theories and hypotheses commonly found in the literature. I first focus on research that views the state as being reactive and investigates how governments respond to protest. Then I discuss the main arguments that have been developed on how the use of repression influences protest behaviour. In each of these sections I discuss how political regimes in general, and democracy in particular, have been found to influence both protest and repression.

When we consider instances where citizens have voiced their discontent with the ruling government in various shapes and forms, governments are generally keen to put an end to the show of dissent. Sometimes, governments act with restraint, while at other times government forces unleash extreme and widespread violence against the protesters, and even against bystanders and the wider population. The question is when do governments use violence and repression as a response to dissent? The following section discusses the main reasons why governments use repression as a response to dissent.

Internal unrest is generally found to increase repression (Davenport 1995; Tilly 1978). Past research has shown strong support for the argument that countries are more likely to suffer from torture, extrajudicial killings and political imprisonment during times of civil war (e.g. Krain 1997; Poe and Tate 1994; Zanger 2000), where civil war is an extreme example of instability and popular resistance. More generally, the empirical literature has provided substantial support for the argument that dissent, such as in the form of strikes, demonstrations or guerrilla warfare, increases the use of state coercion (Davenport 2005; Davis and Ward 1990; Gupta et al. 1993; Gurr and Lichbach 1986; Poe et al. 1999; Regan and Henderson 2002). The main theoretical reason that has been presented for violent government responses to dissent activities is that the authorities resort to violence in order to restore their political control by extinguishing dissent. Unrest and protest are perceived as a threat to government authority and legitimacy, therefore governments use force to strengthen their position and to eliminate the threat (Boudreau 2005; Davenport 1995; Poe 2004). Dissent – particularly violent forms of protest – is often interpreted by governments as sufficient justification for the use of force in order to restore ‘law and order’ (Davenport 2007a).

Mason (2004) suggests that governments in developing countries often respond with a disproportional amount of violence to non-violent collective action because institutional mechanisms for accommodating grievances are missing or underdeveloped. Davenport (1995) argues that governments distinguish between different forms of threat when they employ negative sanctions. He finds that governments increase the level of sanctions when faced with a higher number of dissent activities, when different forms of protest are employed, and when the activities lie outside the norms of interaction in that country. Analysing government and dissident behaviour in Peru and Sri Lanka, Moore argues that ‘states tended to substitute accommodation for repression and repression for accommodation whenever either tactic was met with dissent’ (2000: 120). Gartner and Regan (1996) find that government repression does not always increase proportionally with increasing dissent. Their study of 18 Latin American countries suggests that as the demands of the dissidents increase, governments react with more restraint. Additionally, governments appear to overreact to relatively low demands with violent coercion.

Not all governments respond to dissent in the same way. For example, when shantytown dwellers in Chile illegally seized land in 1983 under the military regime of General Pinochet, they were arrested and severely repressed by the security forces of the military junta. Six years later, after the democratic election of President Aylwin, shantytown dwellers again seized land illegally, but this time the reaction consisted of verbal condemnation, not violent coercion (Hipsher 1996). Clearly, the nature of the political regime has an important influence on a government’s use of repression. Political regimes reflect the norms that guide political interactions and the institutions through which those interactions are channelled. They determine the levels of power and force that can legitimately be used against citizens, and facilitate the accommodation of opposition grievances. Democracies are generally associated with non-violence (Rummel 1997). Democracy

institutionalizes a way of solving without violence disagreements over fundamental questions. Democracy promotes a culture of negotiation, bargaining, compromise, concession, the tolerance of differences, and even the acceptance of defeat … And it unleashes forces that divide and segment the sources of violence.

(Rummel 1997: 101)

In short, in a democracy, norms and institutions are in place that make it less likely for governments to resort to violence against their own citizens. Democratic political institutions facilitate the inclusion of opposition groups and provide legitimate channels for regime opponents to voice their discontent in non-violent ways. At the same time, they provide the government with tools and procedures to engage with the opposition in a peaceful and institutionalized framework. Therefore, democratic institutions render opposition grievances less threatening, reducing the incentives for governments to react harshly to dissent. Democratic institutions also attach a high cost to state coercion. A government is less likely to employ violence against its citizens if it needs the support of the general public in order to be reelected into office. At the same time, democratic norms lower the willingness of all actors to resort to violence in solving disagreements and conflicts between the ruling government and potential dissidents.

While most studies agree that dissent provokes government coercion, particularly in non-democratic countries, the picture is less clear when we turn the relationship around and ask how state coercion influences protest.

There is an abundance of contradictory theorizing and empirical evidence about whether state repression increases or decreases the incidence of social protest.1 Zimmerman summarizes the situation as follows:

There are two contradictory expectations about the effect of governmental coercion on protest and rebellion: coercion either will deter them or will instigate people to higher levels of conflict behaviour…. Thus there are theoretical arguments for all conceivable basic relations between governmental coercion and group protest and rebellion except for no relationship.

(Zimmerman 1980: 191)

Over two decades since Zimmerman’s evaluation, the picture of the repression–protest nexus has not become substantially clearer. Davenport calls for ‘the replication of analyses within diverse contexts’ (2005: x), the use of diverse methodologies and datasets in order to advance our knowledge on how repression impacts upon dissent. This book addresses some of those concerns by applying complementary methodological approaches to investigate different sets of data that cover a range of different contexts. It employs three types of empirical investigation of the protest–repression nexus in Latin America and Africa. The first analysis examines the relationship between protest and repression on a macro level, using yearly data from 43 countries from sub-Saharan Africa and 23 countries from Latin America between 1977 and 2002. The main advantage of this analysis is that it provides information about the general nature of this relationship in these two regions, while controlling for important variables. The second analysis focuses on the dynamics of the relationship by investigating daily data from six Latin American and three African countries. The two main contributions of this second analysis are that it specifically models the interdependence between protest and repression, and that it includes cooperative behaviour in the analysis of domestic conflict. The final analysis focuses on the micro level. It presents two illustrative case studies, one of Chile and one of Nigeria, to show how the interactions between government and non-government actors have played out in specific circumstances. These qualitative case studies allow tracing the causal chain in more detail compared to the quantitative analyses.

The main theories that explain how state repression influences protest and rebellion can be divided into two broad categories: theories that are based on psychological factors, such as perception of inequality by potential rebels, and those that focus on rational behaviour, either of the individual or of groups, in terms of mobilizing structures.2

Relative deprivation theory has been widely used to explain and predict domestic rebellion and dissent (e.g. Davies 1962; Ellina and Moore 1990; Gurr 1968, 1970; Muller 1980; Muller and Weede 1994). The main argument of this theory is that people who feel deprived relative to their expectations are more likely to protest and rebel against the regime. Gurr argues that ‘[d]iscontent arising from the perception of relative deprivation is that basic, instigating condition for participants in collective violence’ (1970: 13).3 The main cause for social dissent is the frustration of people, not cost– benefit calculations or mobilization by leaders. Gurr outlines that

the primary source of the human capacity for violence appears to be the frustration–aggression mechanism…. If frustrations are sufficiently prolonged or sharply felt, aggression is quite likely, if not certain, to occur…. The frustration–aggression mechanism is in this sense analogous to the law of gravity: men who are frustrated have an innate disposition to do violence to its source in proportion to the intensity of their frustration.

(Gurr 1970: 36–7)

Frustration is defined as ‘a discrepancy between value expectations and value capabilities, where value expectations are the amount of important goods and conditions of life to which people feel rightfully entitled and value capabilities are their assessment of what they actually have’ (Muller and Weede 1994: 41). Relative deprivation creates anger, which leads to protest. Looking at the relationship between repression and dissent, relative deprivation theory predicts that repression increases protest, where repression is perceived as depriving citizens of their right to be free from coercive actions by the state. Relative deprivation theory is, at its core, a psychological theory.4 It uses people’s frustration levels to determine their proneness to rebel against the political regime.5

As Mason points out, relative deprivation theory generally over-predicts dissent and revolution (Mason 2004: 35). In many countries, at many points in time, many people have felt frustrated about their political or economic situations, and perceived themselves to be substantially worse off compared to their own expectations, yet rebellions or revolutions have been relatively rare events. Focusing on civil war and rebellion, Collier (2000) points out that even if people feel deprived relative to their expectations or are frustrated with an unjust regime, they would need to overcome the problem of collective action to organize potential rebels (Lichbach 1995; Olson 1993). Therefore, the greed of individuals needs to be instrumentalized in order to organize a rebellion. Collier (2000) argues that rebels can be motivated by greed, by accumulating private wealth and resources in illegal ways during conflict. Without the opportunity to satisfy individual greed, rebellion is not expected to take place (Collier and Hoeffler 2004; Fearon and Laitin 2003).

Several theories have focused on the problem of collective action for dissent. In the following, I introduce resource mobilization theory, which focuses on the organizational processes of protest mobilization, before discussing the main arguments of micromobilization theory, which also concentrates on mobilizing structures, but at the individual instead of the organizational level.

Resourc...