- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This challenging study brings together anthropology and political science to examine how ethnic minorities are constructed by the state, and how they respond to such constructions.

Disclosing endless mini negotiations between those acting in the name of the Chinese state and those carrying the images of ethnic minority, this book provides an image of the framing of ethnicity by modern state building processes. It will be of vital interest to scholars of political science, anthropology and sociology, and is essential reading to those engaged in studying Chinese society.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Negotiating Ethnicity in China by Chih-yu Shih in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Civics & Citizenship. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

Inside “China moments”: ethnicity as legality and policy

Becoming China

Today, it is not difficult for elementary-school children to point out on a world map where China is. Except for an extremely small number of experts, however, few can describe the nature of China’s various territorial disputes. Perhaps only those living in Taiwan, where the government continues to include Mongolia as part of China on maps, are aware that “China” is not a simple geographical entity. Leaders of pre-sovereign China had never needed clear borders. Giving it such borders now will only deny the moral superiority they feel, which crosses human-made boundaries of all kinds. Nor had the Chinese been known for drawing lines to indicate ethnic distinction. In fact, many groups of people who were originally not considered Chinese became Chinese simply by acquainting themselves with the Chinese Confucian and Daoist way of life while either conquerors of the Chinese Empire, which felt itself to be ruler of “all under heaven,” or victims of celestial conquest. At best, China has been a country of changing ethnic composition. Yet even this conceptualization may not be accurate.

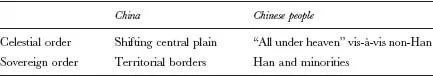

China, which used to mean “the beautiful flower in the center” (signified by the notion of the “central plain” – China’s highest moral symbol) has been a sovereign state since 1911. The flower could move, and so could the “central plain” where each successive court located its capital. Perhaps the only factor of pre-sovereign China consistent with its twentieth-century counterpart is that it had a symbol, which took the form of the Emperor or the Son of Heaven. However, no single imperial family could reign forever. The number of people subscribing to the celestial order determines the physical border of “China as a symbol of all under heaven.” China was thus a concept defined by people instead of by territory. Yet the definition of the term “Chinese people” was even more obscure than the definition of “China.” A quick look at the number of different ethnic groups from remote areas who at some time conquered the central plain reveals the complex synthesis that is the Chinese people. The offspring of those who, for various reasons, decided to move away from the central plain may continue to call themselves Chinese at the beginning of the twenty-first century. On the other hand, others may never have realized that their ancestors were once “under-heaven” Chinese.

Interestingly, when US president Bill Clinton and Chinese president Jiang Zemin met in 1998 in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), there did not seem to be any question about where China is or who the Chinese are. When Clinton pressed hard on behalf of the Chinese in terms of their human rights and Jiang claimed that the Chinese had their own human rights philosophy, their mutual understanding on an unproblematic China or Chinese people was striking, though unnoticed by most in the audience. Neither leader wondered if their disagreement on human rights arose from different views of what constitutes an essential China and/or an essential America. In retrospect, it was precisely this kind of interaction, though under a different setting, that had given birth to the concept of “sovereign China” in the first place. Most scholars would probably trace the origins of the “misconception of China” back to the Opium War.

History books on the modern Chinese typically start with the topic of the Opium War. The celestial Qing court under the sinicized Man imperial family suffered greatly before realizing that the lack of a clear boundary to “under heaven” no longer suggested universal benevolence but, rather, vulnerable indefensibility. Closing it up seemed to be a desirable option. The court’s inability to defend the territory, however, led it to appreciate the newly introduced notion of sovereignty. The court officials, as well as the revolutionaries who overthrew them later, understood the importance of protecting and strengthening Chinese sovereignty as a critical element to reviving “China.” In other words, “sovereign China” was China’s response to Western imperialism. Interestingly, people inside sovereign China today are so preoccupied with the shame brought about by imperialist intrusion that they do not recall that neither pre-sovereign China nor the Chinese people had any sovereign borders, or for that matter nationalist pride. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), on the first page of its own history, presumes the authenticity of China and the Chinese people throughout China’s history:

Modern China began in the mid-19th century, suffering foreign capitalist imperialism and domestic feudalism and sunk in the abyss of bitter predicament and extreme shame. The sovereignty of the country was deprived. … The Chinese people entered the 20th century with the national shame of the rape of Beijing by the Allied Forces. At that time, what lay ahead of the Chinese people seemed to be a prospect of miserable darkness at the brink of destruction.1 [my emphasis]

To reinvent China as a nation with sovereign borders has required intense and continuous effort. Two general goals emphasized by political leaders of the early People’s Republic were to unify the country and to strengthen it.2 Both these goals presupposed that China was already a defined territory. However, the goal of unification implied the existence of “splitters” who served as both the target of and the force pushing for nationalism, and the goal of strengthening implied weakness and the need for state-building. The obsession with eliminating these splitters as well as ameliorating so-called weaknesses guaranteed that China as a sovereign entity was beyond questioning. Unification and modernization have become intrinsic elements in all discourse on China since the beginning of the Chinese sovereign state. It was the general belief among political leaders that the calls for modernization and unification reinforced each other. Therefore, following this line of reasoning, they felt that it was weakness that bred the splitting forces, and that the splitting forces obstructed modernization.

Nationalism and its secular goal of unification have faced two fundamental threats. One was disintegrating power, whose consequences were the Civil War in 1949 and the splitting of China into the Communists’ People’s Republic and the Nationalists’ Republic of China, located in Taiwan. Whether China will reunify in the future has been a question constantly raised by both sides. The other threat was from peripheral habitats where ethnic communities were yet to share the state citizenship of China. China was split into two, divided by the Taiwan Straits. Both sides have continued similar missions, and each has maintained its own sphere of influence. Their common goals are to modernize the state and to mobilize citizens’ loyalty (away from family, religion, and tradition and toward a distant, abstract state). The Communists perceived alienation among previously Nationalist-ruled areas and peripheral ethnic communities, and the Nationalists struggled to win support from the Taiwanese, who had previously been colonized by the Japanese, and to maintain a nominal connection with Tibet and Mongolia on the Chinese mainland. The People’s Republic devised all kinds of mass campaigns to reach its ends, including agricultural collectivization, the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, the Four Modernizations, and Reform and Openness to the Outside World. The cycle coincided with the rise and fall of the Cold War, which featured politics of suppression that subjugated ethnic politics until the early 1980s. At the same time, Taiwan witnessed a period of turmoil and state-building, such as Terminating Insurrection, through the Chinese Cultural Renaissance, and The Ten Great Constructions, then into the current Democratic Reformation. Ethnic identity politics did not revive in Taiwan until the late 1980s.

Ethnic politics is essential in defining the meaning of China. It pertains simultaneously to unification and modernization. Ethnicity indicates where the potential splitters may exist that threaten national unification, as well as the backward forces that hamper state-building.3 Both denying the relevance of ethnicity and promoting it are at best different strategies pursued by the Chinese leadership in the process of state-building. In addition, a change in ethnic politics would immediately involve the unification issue. This is especially true where unification is still seen as a worthy cause. The dominant discourse on the surface is nonetheless about creating modernity – but a modernity whose meaning is still in question, having lingered since the late Qing Dynasty. The debate between the liberals and the New Left continues today: Is the call to modernize China a call to individualism or to collectivism? What role do the masses (peasants, workers, and soldiers) have in bringing modernity to China? Was the pre-reform history of the PRC simply feudalism, or was it a different kind of modernity?4

In the debate on the nature and the path of Chinese modernity, there is no reference to the likelihood of achieving the various ethnic notions of modernity. This hiatus parallels the consensus that the pre-1949 history of China was feudal, backward, and unworthy of mention. China will be hindered in the process of becoming China for as long as modernity and unification remain dreams unfulfilled in ethnic areas.

Becoming minorities

The study of ethnic consciousness is a study of the relationship between China’s small numbers of ethnic minority people and the vast majority of Han Chinese. More precisely, it is a study of ethnic relationships within the same sovereign territory. Ethnic minorities are no longer minorities existing outside national sovereignty. “Minority” is a notion meaningful only in comparison with a majority and is therefore premised on a fixed territorial confinement.5

In China, it is said that there is a Han majority and fifty-five minorities. Together they form the Chinese nation (zhonghua minzu). The Chinese nation implicitly carries the notion of Chinese territorial sovereignty. Loyalty to the Chinese sovereign state and membership of the Chinese nation are two sides of the same coin. Strong Chinese consciousness protects ethnic consciousness from confrontation with Han consciousness, whereas low Chinese consciousness creates a defensive attitude on the part of the minorities toward the Han. Therefore a study of ethnic consciousness in China is a study of the Chinese consciousness of the ethnic minorities in China, and this is, in essence, what this book is about.

The Han majority doubtless identifies easily with the Chinese nation. It is common sense that the overseas Han people treat themselves, and are treated by the Chinese, as Chinese, while this cannot be said of the ethnic minorities. How an ethnic individual perceives himself/herself if living outside China is a useful clue to the relationship between that particular minority and the Han. A plausible hypothesis is that the more an ethnic minority identifies itself with the Chinese nation, the less it needs to distinguish the Han from itself. From another perspective, the Chinese consciousness of a minority is stronger if its members feel less need to make a distinction between themselves and the Han.

Paradoxically, China, in becoming a modernized and unified nation, has also become locked within territorial borders. As a result, the “Chineseness” of the Chinese people no longer depends on how loyal they are to the emperor and assimilate the Confucian values of harmony and selflessness. The notion of “Chineseness” has relinquished its fluidity and spontaneity. This development has serious consequences. For example, the relationship between the Han, who have mixed with many non-Han people during the course of history, and non-Han people emerged as an issue once China became a sovereign state. Since the opposition to imperialism gave rise to sovereign China, patriotism became an inherent element of “Chineseness.” Therefore, nobody inside sovereign China retains the freedom to choose their nationality. The Han, leaders of the new country, would inevitably feel threatened should the non-Han fail to give their loyalty to the government. It is this concern that has given rise to the notion of minority groups in China.

The sovereignty discourse did not allow the Han and the non-Han to be governed by spontaneous exchanges, as in pre-sovereign China. Once China was enclosed within sovereign borders, the Confucian values that once guided emperorship could not survive the call for patriotism. Since then, the non-Han people became officially both Chinese and members of minorities. Hence it is easy to see that any foreign attempts to speak on behalf of these minorities will be regarded as intrusive by all the peoples of sovereign China. This is ironic: what imperialism was supposed to have destroyed was the Son of Heaven’s emphasis on people’s hearts and his inattention to physical borders and territory. Protecting this celestial empire now led to its destruction. In short, while the Western concept of sovereignty replaced Confucianism in defining the China discourse, anti-imperialism remained the predominant signifier of sovereignty.

The fact that national leaders need to denounce pre-sovereign spontaneity in order to assert the new form of sovereignty-based unity leads to alienation from what China always meant to their self-identity as selfless rulers. This self-alienation created enormous pressure on the Chinese government to prove that it is always benevolent toward minorities and that minorities are unambiguously and voluntarily Chinese people. In order for the Han government to show benevolence, the minority category was given legal status. There is another important, though latent, function of the existence of minorities. As potential targets of imperialist subversive activities, minorities “reproduce” – as postcolonial writers put it – China and Chinese people as enclosed in constructed sovereign borders. Since minorities are by definition members of the Chinese nation, the differentiation of Han and non-Han brought about by sovereign identity exposes an underlying fear that the Chinese people may not be united in opposing imperialism. The definition of Chinese under a sovereign China thus acquires an oppressive character contrary to the more flexible version of the “under-heaven” Chinese identity.

The Chinese discourse began its transition from the most beautiful flower in the center. Through a shifting central plain and an under-heaven symbol of harmony, it finally merged with the anti-imperialist sovereign state (see Table 1.1). The China discourse underwent an evolution very different from that of the history of sovereignty elsewhere in the world. Retracing the path leading to the rise of sovereign China would be useful to the analysis of international (i.e. inter-sovereign) affairs because it discloses various deep dispositions often inexpressible in the sovereignty discourse. We might ask, for instance, why the leaders of sovereign China appear defensive, irrational, or even occasionally psychotic in the eyes of Westerners. It is thus useful to look at practices of Chinese sovereignty in peripheral areas in order to appreciate what the leaders of sovereign China experienced. These practices also reveal how they struggled to win recognition, as well as the anxiety inherent in their leadership.

Table 1.1 China discourses

Resistance to Western intrusion forced China to adopt the concept of sovereignty into its present-day structure. In order to facilitate the resistance, China constructed new boundaries that define and distinguish ethnic minorities. Needless to say, the new constructions have led to resistance of different kinds, not to the Western intrusion into sovereign China but to the Han intrusion into minority regions. Ironically, resistance to Han intrusion sometimes relies on Western support. This complex web of resistance may have given certain false impressions to mainstream political science in the West, which either mistakenly foresees an end of history along a so-called liberalization model,6 or a doomed conflict of the bright versus the dark,7 or the emergence of a global civil stratum.8 It is here that the focus of this book engages with mainstream Western scholarship. Is assimilation (the integration of all non-Han people into the Han mainstream) a process of becoming China and therefore anti-Western or is it a process of becoming Western – or, as some recent studies suggest, is it neither of these?

Although the literature offers no definite answers to these questions, recent publications cast doubt on the utility of assimilation policy. For example, Schein demonstrates that sometimes assimilation is no more than a kind of internal Orientalism (the tendency in Western literature to conceptually lock the mysterious alien civilizations into a geographical Orient in order to feel secure),9 making the ethnic community an exotic targ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction: Inside “China moments”: ethnicity as legality and policy

- Part I The ethnic economy of citizenship: comparison with aboriginal Taiwan

- Part II Ethnic sensitivity: contingent identities

- Part III Ethnic traits: after assimilation

- Part IV Ethnic religion: the adaptation of islam

- Part V Ethnic language: educational practices

- Part VI Ethnic schooling: sluggish enrollment

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index