![]()

1 Introduction

A study of movement and order

The movement of people is provoking worldwide anxiety and apprehension and casting long-established patterns of cultural identity, belonging, and security into a state of uncertainty. In this troubled context, abrasive rhetoric about migration is gaining popularity; nation-states around the globe, especially Western ones, are cracking down on migration for security reasons.

Multilateral and bilateral agreements have been signed, international and domestic institutions have been created, extradition and deportation agreements between receiving and sending states have been authorized, and conventions and protocols have been ratified with, at their core, the linkage between migration and security. A sharp increase in border control is also noticeable: by the end of the 1990s (i.e. before 9/11), the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service had more employees authorized to carry guns than any other federal law enforcement force (US Department of Justice 2000). International migration has become a key security issue and is perceived, in some eyes, as an existential security threat. Scholars have referred to this current state of affairs as securitized migration or as the securitization of migration (Wæver et al. 1993).

This book is about the movement of people and the system of order underpinning the movement. In undertaking a comparative study of Canada and France between 1989 and 2005, the study analyzes the process of securitizing migration. That is, it explores the process of discursively and institutionally integrating international migration into security frameworks that emphasize policing and defense (see Huysmans 2006).

To be sure, migration has been controlled through national policies and bilateral and/or multilateral agreements for a long time. Moreover, the notion that certain individuals could pose security threats has been a reality for many years. The factors that have recently begun to cause alarm, however, are (1) the notion of migration in a collective sense posing an existential threat to the security of the state and/or the society; (2) the prominence given to immigration as a security threat; and (3) its attendant effects in political practice, which have undergone significant and even startling changes.

Since the late 1980s, there has been a wave of academic interest in the relationship between the movement of people and world politics. Unsurprisingly, the nature and mechanisms of the securitization of migration is the subject of considerable debate.1 In international relations (IR), scholars attuned to realist premises of anarchy and material interest argue that Western states should fear the “coming anarchy” associated with mass migration (Huntington 2004; Kaplan 1994). Another stream of theorizing that has its roots in IR is neoliberalism; Christopher Rudolph (2003, 2006) revisits the grand state strategy perspective and contends that the “structural threat environment” is the primary explanatory factor for the securitization of migration. Another model, which takes its cue from critical security studies (largely defined) and political sociology, is the governmentality of unease model. Didier Bigo, one of the most active advocates of this model, argues that the securitization process has to do above all with routinized practices of professionals of security and the transformation of technologies they use (Bigo 2002, 2008). Of these models, Securitization Theory (ST) provides the most widely applied and fully developed model for the study of the securitization process (Buzan et al. 1998; Wæver 1995).2 Nonetheless, ST has difficulties finding a place within wider categories of IR theory as realists and neoliberal institutionalists treat ST with polite neglect and critical theorists find ST not critical enough (Booth 2005a; Smith 2005; Wyn Jones 2005).

This book seeks to advance both ST and its engagement with IR theory by linking ST to constructivism—an approach that ST borrows but has not yet explored to its full potential. I argue that constructivism offers sound theoretical foundations to propose refinements to ST. My argument is not that ST should find its “home” in constructivism. Nor is my objective to propose a constructivist model for the study of the securitization process that would stand in opposition to ST. Rather, I want to suggest that constructivism offers fruitful correctives that can be integrated within ST without distorting the theory. My goal is to propose a refined version of ST.

The argument

In this book I make three contributions to the securitization research literature. First, I argue that a departure from ST’s analytical axioms of “conditions” toward a constructivist approach stressing the importance of multifaceted contexts and the inter-relationship between agents and structural/contextual factors is needed. A constructivist perspective underscores that linguistic utterances are always produced in particular contexts and that the social properties of these contexts endow speech acts with a differential value system. My study presents an analytical framework that understands the relationship between agents and contextual factors as mutually constituted, durable but not static, generative, and structured. My analysis also permits the inclusion of time in the analytical framework by opting for a “moving pictures” approach to the phenomenon of securitized migration, instead of taking merely a “snapshot” view of the phenomenon, to borrow a forceful image from Paul Pierson (2004).

Second, I put forward a constructivist approach that acknowledges the polymorphous character of power. Building on the work of Michael C. Williams (2007) and of Michael Barnett and Raymond Duvall (2005), my study underlines that power operates through diffuse processes embedded in the historically contingent and multifaceted cultural settings. Seen in this light, I contend that ST identifies only conditions that facilitate the securitization process; the theory overlooks contextual factors that constrain or limit the securitization process. In addition, I demonstrate that the power of contextual factors does not function in a binary, direct, and almost mechanical way, as is currently understood in securitization research. Rather, my study shows that the power of contextual factors works in a diffuse yet tangible way, and within a continuum of power ranging from enabling to constraining capacities.

Third, I propose a model for the study of the securitization of migration that offers guiding principles to account for the variation in levels of securitized migration. Indeed, I argue that, because ST treats security as a binary notion, it cannot explain variation in levels of securitized migration. The only variation that ST recognizes is along the spectrum of non-politicization, politicization, securitization, and de-securitization. Once an issue reaches the securitization phase, ST does not distinguish whether the issue is strongly securitized or weakly securitized. This is problematic because if variation does exist there is no theoretical space in ST, as currently organized and applied, to provide adequate guidance for the suggestion of hypotheses accounting for variations within cases across time or across cases. Contrary to this standpoint, my analytical framework will permit both an empirical measurement of levels of securitized migration and the deduction of hypotheses to account for the variation.

Methods of inquiry

In the following chapters, I explore the role of two securitizing agents (political, media) and of two contextual factors (exogenous shocks, domestic audiences) in the securitization process. For the purpose of this study, political agents are elected politicians and members of the government—those who are in power. I have focused my analysis on the leaders of the governing political party as well as the ministers in charge of foreign affairs and immigration portfolios.3 In Canada, my political agents are Prime Ministers, Ministers of Foreign Affairs, and Ministers of Citizenship and Immigration. In France, I have chosen Presidents, Prime Ministers, Ministers of Foreign Affairs, and Ministers of Interior. For each agent I examined their complete set of speeches made between 1989 and 2005. In total, I have retrieved, collected, and quantitatively and qualitatively analyzed nearly 3,500 speeches.

In this study, media agents are editorialists of major national newspapers. In Canada, my media agents are editorialists from The Globe and Mail and La Presse. The former is generally regarded as Canada’s national newspaper and the latter as the most important French-language newspaper. Taken together, they have a daily circulation of more than 500,000 copies (weekdays). In France, I have selected editorialists of Le Monde and Le Figaro; their combined daily circulation is also substantial with on average 850,000 copies (weekdays). These two newspapers are largely considered the two most important newspapers in France. For each media agent I examined the complete set of editorials written between 1989 and 2005 in which the issue of the movement of people was discussed. In total, I have systematically retrieved, collected, and quantitatively and qualitatively analyzed 900 editorials.

This selection of agents is not a theoretical statement on who constitutes a securitizing agent; in designing the study, I had to limit the range of agents under investigation. Likewise, although this research investigates actors involved in the securitization of migration, the emphasis is not on the authors of the securitization—if such a role exists. As Hannah Arendt (1958: 184–5) underscores superbly,

the stories, the results of action and speech, reveal an agent, but this agent is not an author or producer. … The perplexity is that in any series of events that together form a story with a unique meaning we can at best isolate the agent who set the whole process into motion … we never can point unequivocally to him as the author of its eventual outcome.

On top of the quantitative and qualitative analysis of politicians’ speeches and editorialists’ editorials, I conducted a limited but well-targeted number of interviews in each country case using a multiple-choice questionnaire, semi-structured questions, and open-ended questions. In Canada, I interviewed eight senior bureaucrats from five departments/agencies; in France, I interviewed eight individuals from three departments. Without revealing their identities, among the interviewees were national security advisers, executive directors, an assistant deputy minister, a vice-president of an enforcement branch, and senior immigration policy advisers.

An exogenous shock refers to an event or a group of events that induce points of departure from established sociological, cultural, and political patterns. The so-called “refugee crisis of the 1990s” and the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 are particularly relevant exogenous shocks in the present context. This is not to say that Canadian and French larger historical contexts, the geographic location of each country, the bombing of Air India Flight 182 in 1985 in the case of Canada, or key judicial landmarks (for instance the Singh case in Canada) were not important in the securitization process. In fact, I briefly discuss these contextual factors in Chapter 2. However, I argue that the refugee crisis of the early 1990s and the terrorist attacks of 9/11 are the most important exogenous shocks in the years that this study covers (1989–2005).

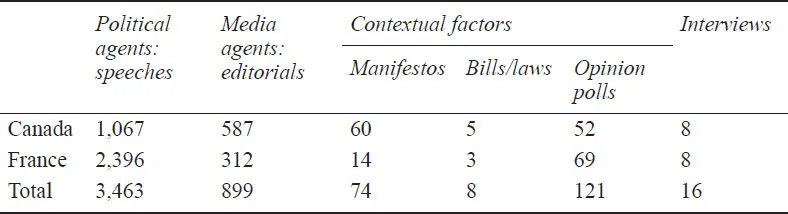

With regard to domestic factors, I investigate the role of audiences for reasons that will be established in the theoretical discussion that follows. Obviously, numerous other domestic factors could be important in the securitization process. My focus on audiences is not meant to be a theoretical statement on what could be a contextual factor involved in the process. Rather, I am confining my study for purposes of feasibility to an exhaustive analysis of a particular set of contextual domestic factors that are undeniably central to the process of securitizing migration, without discounting that others play roles as well. I draw on three principal sources to track down how audiences shape the securitization process. First, I have collected the political manifestos of the main federal political parties in Canada as well as the most important presidential candidates in France. In total, I have analyzed more than seventy political manifestos. Second, I examined the extent to which Parliament has allowed or constrained securitizing actors’ moves by analyzing whether the most important immigration laws regarding the securitization of migration were passed, narrowly passed, or defeated in each country case. I have examined five pieces of legislation in Canada and three in France. Third, I have examined public opinion on questions related to the migration–security relationship. In total, I have collected and analyzed more than 120 public opinion polls, as Table 1.1 summarizes.

Table 1.1 Corpus of research

The primary research method that I employ in this study is a traditional content analysis. To give further robustness to my findings, I use the logic of triangulation of methodological approaches: I have tried throughout the study to check findings obtained with one research method against findings attained from another type. For instance, I employ a content analysis of every speech by a given agent to understand how this particular agent perceives the issue of international migration. What is he/she talking about when he/she talks about the movement of people: is it to highlight the benefits of multiculturalism, to underscore the difficulties of immigrants to integrate the job market, to celebrate the diversity and the richness that immigrants bring to the host society, to question to efficiency of the refugee determination process, and so on. In the next step, I isolate the securitizing moves, that is, when an agent argues that international migration is a security concern for the state and/or the society. Then, I use statistical analysis to provide a graphic overview of the pattern of engagement of each securitizing agent with the phenomenon of securitized migration and to further study the relationship between migration and security. To check for any discrepancy between these findings, I use interviews with senior bureaucrats of several departments/agencies. In addition, I employ survey and poll research as well as socio-historical analysis to capture the role of public opinion and contextual factors in the securitization of migration.

Boundaries, significance, and logics

For my purposes, migration is the movement of people crossing international borders; this includes the United Nations’ largely accepted definition of migrants as persons living outside their country of birth or citizenship for 12 months or more, but it also includes refugees, foreign migrant workers, student migrants, border workers, denizens, and legal and “extra”-legal migrants. Because the focus of this study is on the international aspect of the movement, I have excluded internally displaced persons (IDP) from the analysis.

Employing this rather broad definition makes sense for several reasons. First, the aim of the study is to examine how the international movement of people has been socially constructed as a security concern in Canada and France. As such, the focus is on the deeply intertwined relationship between the international movement of people and the international system of order underpinning the movement. Second, precise distinctions between, for example, legal and illegal migrants or migrants and refugees would limit more than they would reveal, despite the fact that these distinctions render a better understanding of the term “migration.” Indeed, I contend that a security framework is not applied only to refugees but rather to the entire category of the movement of people.

Critics might contend here that the object of securitization is not the movement of people in its totality but the more circumscribed aspects of the phenomenon of migration (e.g. illegal/irregular migration, refugees), therefore calling for a narrower definitional positioning. They eschew two fundamental elements. First, states’ authorities define what constitutes an irregular/illegal migrant. There is no multilateral coordination between countries on what is an illegal migrant. An illegal migrant in France could well be a legal migrant in Canada. Neither theoretically nor empirically does our understanding of the illegal versus legal migrants dichotomy necessarily have to be that of a particular state. As Morice and Rodier (2005) argue, classifying migrants and refugees creates a harmful distinction in the context of a state’s attempt to control migratory movement under national security concerns; the classification process is not neutral.

Second, it is the malleability of the concepts of “migration” and “security” that makes them especially useful in politics (Edelman 2001). As the following chapters demonstrate, the state’s security apparatus purposively provokes an elision and confusion of migration categories. Overdrawing an analytical distinction between several categories of migration would indeed miss the “flexibility” quality that politicians have been particularly eager to exploit. Indeed, research focusing merely on “illegal” migration would miss important features of the phenomenon of securitized migration, such as in cases when legal would-be immigrants have been detained for several days before being granted permission to stay in France, or when legal tourists have been “strongly” invited to board a plane bringing them back to their country of origin the day after their plane landed in Vancouver.

The questions and answers that this study provides are timely and relevant for several reasons. First, we do not have a profound understanding of the mechanisms at play in the securitization process. The curr...