- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Keynesian Multiplier

About this book

The multiplier is a central concept in Keynesian and post-Keynesian economics. It is largely what justifies activist full-employment fiscal policy: an increase in fiscal expenditures contributing to multiple rounds of spending, thereby financing itself. Yet, while a copingstone of post-Keynesian theory, it is not universally accepted by

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Keynesian Multiplier by Claude Gnos,Louis-Philippe Rochon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Some views on the multiplier

1 Three views of the multiplier

Jochen Hartwig1

Introduction

This chapter endeavours to re-interpret one of the most fundamental concepts of macroeconomics: the Keynesian investment multiplier. It is demonstrated that there are three different views of the multiplier in Keynes’s own works, and that only one of them is in line with the principle of effective demand as exposed in chapter 3 of The General Theory.

The chapter is organised as follows. First, what I call the ‘traditional interpretation of the multiplier’ is restated. This traditional view is then criticised for its lack of logical coherence and ‘realisticness’.2 It is argued that the multiplier and Keynes’s principle of effective demand constitute an analytical unity; therefore it is necessary to restate the principle of effective demand. This is done somewhat differently than in the existing (post-Keynesian) literature on effective demand.

The subsequent section elaborates on what is here called Keynes’s ‘third view’ of the multiplier—the one that is held to be compatible with the principle of effective demand. This ‘third view’ envisages the multiplier as an equilibrium condition that prescribes the proportionality between the two ‘departments’ of the economy—the consumption- and the investment goods sectors—necessary for what is here called ‘completely successful reproduction’. The Marxian concept of reproduction schemes is combined with Keynes’s ‘fundamental psychological law’ (which states that the marginal propensity to consume is ‘positive and less than unity’; Keynes, 1973a, p. 96) to derive this result. Some dynamic aspects of the ‘third view’ of the multiplier are briefly discussed. The final section traces back the ‘third view’ of the multiplier—which seems to have escaped the attention of a wider audience so far—to Keynes’s own writings. The last section offers some conclusions.

The traditional interpretation of the multiplier

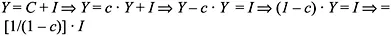

The issue of the multiplier seems to be settled. Everybody knows what it is. Textbooks usually present the familiar relation for a closed economy without state activity:

where Y=income, C=consumption, I=investment and c=marginal propensity to consume. This calculation starts from the ‘expenditure perspective’ on national income. National income is at disposal either for consumption or for investment. But in the second step the perspective switches, so to speak, to the production account: if (an additional) income is somehow generated, some part of it will be consumed. After several simple mathematical manipulations a relation between investment and national income emerges which is known as the ‘multiplier relation’. Keynes gave prominence to investment as the ‘prime mover’ in the process of income generation,4 because the multiplier relation ‘proves’ that every increase in investment increases national income multiplicatively by [1/(1−c)], and that every decrease in investment decreases income by a much larger amount than the value of investment itself.

But how can a certain investment demand increase national income by a factor greater than 1? The pure existence of a mathematical or logical relation does not yet provide an answer to this question. Besides the multiplier relation there must be some multiplier process. The traditional view of this multiplier process has been cogently stated by James Meade:

Suppose…that we start with a given level of the flow of investment expenditures. This is sensible because investment is in fact influenced primarily by outside or ‘exogenous’ influences such as the confidence and expectations of businessmen in the case of private investment and governmental decisions in the case of public investment. These investment expenditures will generate the payment of wages, rents, interest, profits etc. to those engaged in the production of these capital equipment in question. Those engaged in the production of these capital goods will save some of the incomes so earned but will spend the rest on consumption goods. The producers of these consumption goods will thus earn incomes, part of which they will save but part of which they will in turn spend on other consumption goods, thus generating still other incomes which will be partly saved and partly spent on consumption, and so on. This process will generate a converging series of ever diminishing waves of expenditures which will result in a finite level of demand for goods and services to meet both the original investment demand and the subsequent induced demands for consumption goods. The level of economic activity so generated may or may not be sufficient to provide full employment for the available productive resources in the community.

(1975, p. 84)

In the beginning, before production has taken place, there is an investment demand which is then satisfied by production. Due to this production activity in the investment goods sector, income is generated which induces a demand for consumption goods. In an infinite process of demand-production-income generation-demand, the final outcome will be the one given by the multiplier relation.

As is well known to post-Keynesians, ‘Keynesianism’ has often misinterpreted Keynes—but not in this case! Keynes described the multiplier process in the same way as Meade:

There is nothing fanciful or fine-spun about the proposition that the construction of roads entails a demand for road materials, which entails a demand for labour and also for other commodities, which, in their turn, entail a demand for labour… Generally speaking, the indirect employment which schemes of capital expenditure would entail is far larger than the direct employment… But the fact that the indirect employment would be spread far and wide does not mean that it is in the least doubtful or illusory. On the contrary, it is calculable within fairly precise limits.

(Keynes and Henderson, 1972, p. 105, fn.)

Keynes expands on this view in ‘The Means to Prosperity’ (1972). Here, he distinguishes between ‘primary expenditure (employment)’ in the production of investment goods and ‘secondary expenditure (employment)’ in the consumption goods sector.

The multiplier process as it is presented by Meade and Keynes supports two policy prescriptions which are closely associated with the name of Keynes. First, whenever the volume of private investment expenditure is insufficient to ‘generate’ full employment, the government can and should fill that gap. Public investment, or, to be more specific, any public expenditure which creates income for somebody, has the same multiplicative effects as private investment expenditures. Unlike monetary policy, fiscal policy offers the theoretical possibility to create full employment under all circumstances.

The second policy prescription concerns the role of saving. Whereas for a neoclassical economist high saving (and perhaps also a high interest rate which encourages high saving) is welcome because the non-consumption of resources is believed to be the supply-side requirement for high investment, high saving has a detrimental role for Keynes. It is obvious that the investment multiplier [1/(1−c)] increases if the marginal propensity to consume (c) converges to unity. For this reason, Keynes considers high saving as disadvantageous: it appears to be a ‘leakage’ out of the income-generating multiplier process. To quote Meade again:

Investment expenditure could be regarded as an injection from outside of a flow of purchasing power into an income-generating system; saving could be regarded as a leakage of purchasing power out of this income-generating system. Given an initial injection of investment demand into the system, incomes would be generated by a succession of waves of induced demand for consumption goods until the resulting leakage out (saving) was equal to the original injection in (investment). The greater the level of investment and the lower the proportion of their income which people decide to save, the higher would be the level of the resulting effective demand for goods and services and so the demand for output and for the employment of labour.

(Meade, 1975, p. 84)

Keynes’s proposition that saving always equals investment (1973a, p. 84) implies more than just an accounting identity. The identity of saving and investment is the result of a process in which part of the ‘induced income’ is saved in every ‘round’. At the end of this income-generating process the sum of the savings must be equal to the initial investment expenditure.

Although, according to Keynes, high saving cannot be encouraged, it is important that something is saved, because if nothing was saved at all, the income-generating process would not converge to a point of rest. That is why Keynes sometimes presents his ‘fundamental psychological law’, which states that the marginal propensity to consume is ‘positive and less than unity’ (ibid., p. 96) as a stability condition:

My theory itself does not require my so-called psychological law as a premise. What the theory shows is that if the psychological law is not fulfilled, then we have a condition of complete instability. If, when incomes increase, expenditure increases by more than the whole of the increase in income, there is no point of equilibrium. Or, in the limiting case, where expenditure increases by exactly 100 per cent of any increase in income, then we have neutral equilibrium, with no particular preference for one position over another.5

(Keynes, 1973d, p. 276)

To conclude this section, I restate the first two views of the multiplier in Keynes’s works—those two views that should be well known to economists familiar with the Keynesian literature. According to the first view, the multiplier is a functional relation between a conceivable level of investment expenditure and of income. The multiplier relation implies stability. To grasp this, we can compare the relation between investment expenditure and income at two hypothetical points in (logical) time.6 If the stability condition—the marginal propensity to consume must be smaller than one—is violated, the logical multiplier relation is also invalidated.

According to the second view, the multiplier is a dynamic process (probably in historical time—the literature is not outspoken on this point) that guarantees an increase in national income, caused by an investment ‘injection’. The additional income is greater than the initial investment injection. Two quotes from The General Theory support these two views:

- View 1 (the multiplier is a logical relation between investment and income that implies stability):

The multiplier tells us by how much their (the public’s) employment has to be increased to yield an increase in real income sufficient to induce them to do the necessary extra saving.

(Keynes 1973a, p. 117; my emphasis)

- View 2 (the multiplier is a dynamic process):

Let us call k the investment multiplier. It tells us that, when there is an increment of aggregate investment, income will increase by an amount which is k times the increment of investment.

(ibid., p. 115; my emphasis on ‘will’)

We can perhaps synthesise the two views of the multiplier presented so far—the combination of which constitutes what I call the ‘traditional interpretation of the multiplier’—by saying that the income-generating process would not converge to a point of rest if the marginal propensity to consume was not smaller than one, and in this case the logical multiplier relation could not be maintained. So we might say that Keynes’s ‘fundamental psychological law’ is the connecting link between the two views of the multiplier.

Problems of the traditional interpretation of the multiplier

In this section it will be argued that the traditional interpretation of the multiplier presented above is (a) contradictory in terms, (b) a false abstraction from reality and (c) incompatible with the principle of effective demand as presented in chapter 3 of The General Theory.

The contradictory nature of the multiplier concept can easily be assessed. How can a dynamic process that consists of an infinite series of induced expenditure streams ever reach a final level of national income? In other words: the logical relation between different levels of investment expenditure and income established by the first view of the multiplier mentioned above will only be reached by the multiplier process (view 2) in the limit. It is also noteworthy that, whereas the first view of the multiplier implies that saving and investment are identical, the second view implies that they are different: as long as the multiplier process goes on (and it goes on forever) the sum of savings will be smaller than the initial investment expenditure.

Of course, we face here a central problem of the economics of Keynes: the problem of reconciling dynamic analysis (which proceeds in historical time) with comparative-static analysis (which proceeds in logical time). It was noted long ago that Keynes’s inability to solve this problem eventually led him to turn to comparative st...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of illustrations

- List of contributors

- The Keynesian multiplier: an introduction

- PART I Some views on the multiplier

- PART II Some critical insights on the multiplier

- PART III Toward a re-interpretation of the multiplier