Introduction

Conflicts are intrinsic in the nature of coalitions. Government parties, in fact, are allies but, at the same time, they are organizations competing (with one another) for maximizing votes in the electoral arena (Panebianco 1988). Individual components of the executive, ministers above all, are agents of the whole cabinet, in their respective departmental policy domain, but they are also (at least some of them) representatives of their own party within the government (Andeweg 2000). A tension between centripetal and centrifugal drives, therefore, is inherent in the very nature of coalition executives: something that might be conducive to more or less frequent and serious conflicts among partners.

If intense enough, conflicts might weaken the basis of the alliance and challenge the stability of the executive. Even when less threatening, in terms of risks for government survival, intra-coalition conflicts can undermine cabinet decision-making and government performance.

It stands to reason, therefore, that conflict management is an essential commitment for coalition governments. Coalition governance, indeed, is supposed to be a matter of conflict avoidance, even more than conflict management. Coalition agreements, discussed in depth by Conti in Chapter 3, are supposed to be crucial mechanisms in this regard (Andeweg and Timmermans 2008). Unforeseen, or deferred, issues of conflicts, however, might always arise during the government life cycle (Strøm et al. 2008) and need to be addressed by government partners.

The analysis of conflict management, from this point of view, has proved to be a precious perspective for observing internal dynamics of coalition governments2 and, in this respect, Italy is a very intriguing case to study. Before the 1990s, it was traditionally ruled by often conflictual and ineffective (in most of the cases coalition) governments (Di Palma 1977; Spotts and Wieser 1986). In the absence of any real chance of alternation, fragile governing coalitions were constantly formed around the Christian Democratic party (DC), which traditionally controlled the prime-ministership and the most influential cabinet portfolios (Verzichelli and Cotta 2000). On the one hand, resulting government majorities used to be fragmented and internally divided (as far as the main policy preferences are concerned). On the other, governments used not to be based on formal coalition agreements (Moury and Timmermans 2008). The attitude of Italian First Republic governments to rely largely (if not exclusively) on arenas of conflict management and resolution that were external to the cabinet, therefore, is perfectly coherent with the arguments raised by the most advanced comparative literature on this issue. The common hypotheses, in fact, postulate that conditions like the fragility of coalitions, the bias in favor of one of the governing parties (as in the case of the DC) and the absence of any prior policy agreement among coalition partners, make government members more likely to resort to institutions that are external to the cabinet (such as a committee of parliamentary party leaders), or mixed arenas, open to both cabinet and non-cabinet actors (such as the renowned Italian ‘majority summits’ between ministers and party leaders), rather than to internal (and closed) arenas (i.e., the cabinet) for conflict resolution (Andeweg and Timmermans 2008).

The analysis of intra-coalitional conflicts (and of conflict management) during the Italian Second Republic, therefore, promises to be interesting and valuable. Not only because, as said, it will provide a precious empirical perspective for the observation of the government internal dynamics in an era, as emphasized in the introduction of this volume, of profound (but also uncompleted and even contradictory) transformation of the Italian political system. From a broader comparative perspective, it will also serve as a dynamic test of the same bulk of hypotheses on coalition governments and conflict management mentioned above.

It is true, on the one hand, that the evolution of the Italian political (and institutional) system between the First and the Second Republic has proved largely incomplete (Ceccanti and Vassallo 2004; Almagisti et al. 2014), and that traditional features (and problems) of the Italian governments have remained substantially unaltered (or become even worse) as a result. Fragmentation and heterogeneity have continued to plague government coalitions that were assembled to win the elections and to defeat the ‘opposite pole’, but were also unable to govern (Diamanti 2007) and to produce stable executives (Pasquino and Valbruzzi 2011). Coalition fragility and cabinet instability, moreover, have opened the way to frequent government crises and, sometimes (as in the case of the executives formed after the crisis of the Prodi I government in 1998), to more traditional – First Republic-like – patterns of government formation and coalition governance: i.e., pure parliamentary (not electoral) legitimation of majorities, no pre-electoral coalition deals and policy agreements, subordination to partisan actors outside the cabinet. Under these premises, we could hardly expect to find evidence of a diminishing intra-coalitional conflictuality.

On the other hand, however, the structure of Italian governments has experienced some evident changes in the last 15 years, that we expect to have had an impact on mechanisms of intra-coalitional conflict handling. To say the least, the new bipolar electoral competition between center-right and center-left pre-electoral coalitions (Golder 2006) has led to executives (and prime ministers) with a more direct electoral derivation (and legitimation). The new (for Italian governments) habit of drafting coalition agreements focused on policies with constraining implications on coalition governance (Moury 2012), and the increased cabinet membership rate of party leaders who, instead, used not to sit in the executive during the First Republic (Verzichelli 2009) are two of the main corollaries of this ‘majoritarian turn’ in Italian politics.

Drawing from the already quoted study by Andeweg and Timmermans (2008), who have found that when governing parties have prior coalition policy agreement to rely on, and when party leaders take a seat in the executive, conflicts tend to be solved within closed and internal arenas, we should expect conflict management by the Italian governments of the Second Republic to be somehow ‘internalized’ within the cabinet.

With the aim of verifying these general expectations, the next pages are organized as follows. We first present some basic features of Second Republic governments, with particular focus on the composition (and fragmentation) of the supporting coalitions, as these same characteristics are expected to have an impact on the dynamics of conflict occurrence and management. Intra-coalitional conflictuality is then measured for each single government (by means of an extensive newspaper analysis), as regards to both quantity (the number of conflicts that occurred) and quality (the objects of conflicts and their ‘seriousness’ in terms of the risks they posed to cabinet survival). Third, we provide some information about the role and the involvement of prime ministers in conflicts. The decision-making and conflict management arenas are finally examined (again using newspaper analysis as the main source of information) with particular regard to their openness or closure to actors outside the cabinet.

Government coalitions between 1996 and 2011

The starting point of the empirical investigation presented in this chapter is 1996. While we already have access to sufficient knowledge about intra-coalition conflicts and conflict management during the First Republic (Nousiainen 1993; Criscitiello 1996; Verzichelli and Cotta 2000), no systematic studies regarding more recent years are available. At the same time, we decided not to consider the period immediately following the crisis of the First Republic in 1992, as this was characterized by extreme instability of the Italian government system, and it was ruled, almost entirely,3 by non-partisan, technocratic or quasi-technocratic executives (Fabbrini 2000).

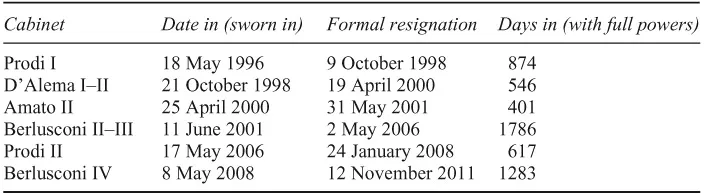

Between 1996 and 2011 four politicians alternated as prime ministers and six coalition governments were appointed. For the sake of simplicity we treat as a single executive two governments following one another, without any change in the prime-ministership and without a general election occurring in between. According to these criteria, the six cabinets are Prodi I; D’Alema I–II;4 Amato II;5 Berlusconi II–III;6 Prodi II; Berlusconi IV. Only the Amato II and Berlusconi II–III cabinets did not terminate prematurely; and only the latter lasted for the entire legislative term.7Table 1.1 indicates the first day in office, the date of resignation of each government, and the duration (in days) with full powers8 of these executives. The four prime ministers, with the exception of Berlusconi, were not leaders of their own parties when in office.9

Table 1.1 Italian cabinets, 1996–2011

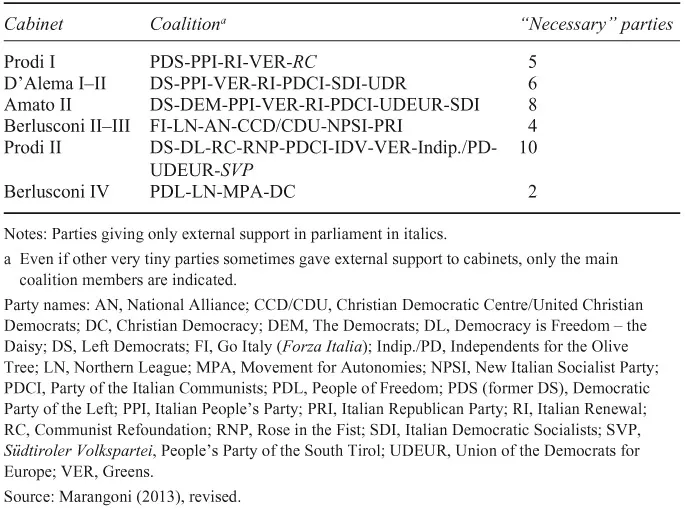

With regard to the party composition, we consider as coalition members all parties explicitly supporting the cabinet in parliament, whether or not they have any representative in the Council of ministers, or any of their members appointed as junior minister.10Table 1.2 reports the party composition of the coalition supporting each government, together with a measure of coalition fragmentation, computed as the number of parties that were strictly necessary to hold the absolute majority in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate (i.e., parties with veto power). Some coalitions were oversized, but the number of parties that were necessary to hold a majority was actually smaller.

Table 1.2 Party composition of government coalitions (at time of inauguration), 1996–2011 (including parties giving external support)

Taken as a whole, data in Table 1.2 confirm that complexity and fragmentation have characterized Italian government coalitions (also) during the Second Republic. There are some variations among governments, but there is not any clear pattern toward simplification of government teams. On the contrary, the most fragmented coalition was the rather recent center-left alliance supporting the 2006–2008 Prodi II executive (ten necessary parties). As we will also discuss in the following pages, even the more homogeneous coalition supporting the Berlusconi IV cabinet (only two necessary parties) experienced significant troubles, due to an increasing level of internal conflictuality during the life of this government (ending up with an early dissolution of the executive).

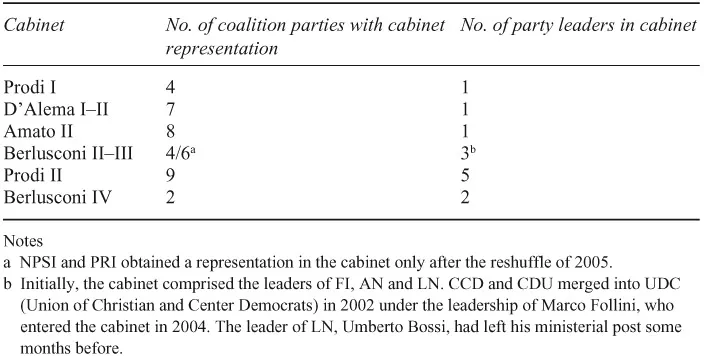

Another aspect to be taken into careful consideration, because it is expected to have a significant impact on the attitude of governments toward conflict management, is the presence of party leaders within the cabinet. We find quite significant differences among the governments under scrutiny on this regard. Overall, the ‘majoritarian’ governments (those led by Prodi and Berlusconi) form a group on their own compared to the more First Republic-like governments (led by D’Alema and Amato), with the exception of the first Prodi government. Indeed, only one party leader entered this latter cabinet. On the contrary, more than half of the parties represented in the Berlusconi II–III and IV and Prodi II cabinets had their own leaders inside the (senior) ministerial group (Table 1.3).