![]()

Part I

Voter turnout

This first part of this book constitutes one chapter examining voter turnout. I begin with voter turnout because, for most citizens, voting is the single most important aspect of their engagement with the political world. This section also frames later discussion. In Part III I will return to some of the themes raised in Chapter 1 by considering the broader dimensions of young people’s political participation beyond voting.

![]()

1

Is turnout declining among the young?

Old people vote, young people don’t. This is the message coming out of much of the academic and popular literature on young people and voting. In this literature young people are depicted as ritual non-voters as compared to older regular voters who are holding up their end of the civic bargain. Book titles such as Is Voting for Young People? (Wattenberg, 2006) typify the tenor of much of the literature on voter turnout among the young. But does this hold true for the Anglo-American democracies? Would this chapter be more appropriately titled ‘why don’t young people vote’?

In this chapter I examine turnout in regards to lifecycle and generational effects on voting. Any study of turnout among the young needs to see turnout in the context of these effects. Lifecycle effects predict that young people will become more involved in electoral politics as they assume the responsibilities of adulthood and move through the lifecycle. Generational effects predict that cohorts will be affected by the circumstances that they grew up in that in turn affect their present and future voting patterns. The assumption in the literature (that finds support for generational effects) is that generational replacement will drive down turnout levels over time as non-voters come to replace regular voters. If this is confirmed this has concerning implications for democracy and suggests that the aggregating mechanism elections play may be compromised.

This chapter shows that generational effects do seem to be at work but not in the way much of the literature assumes. Rather than driving down turnout generational effects seem to be creating more volatile voting patterns by which young people turn out in relatively high numbers at some elections and abstain from others. In support of this proposition is evidence from the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) showing that young people are much less likely than older people to see voting as a civic duty. This chapter shows that rather than characterizing young people as non-voters it would be better to characterize them as volatile voters.

Why is voting important?

Before moving to the analysis it is worth asking why voter turnout should be such a major concern. It could be argued that voting is but one of many forms of political participation (see following chapters for greater discussion). Marsh and Kaase (1979a, 86) went so far as to exclude voting from their analysis of political participation in advanced western democracies arguing that

voting is a unique form of political behaviour in the sense that it occurs only rarely, is highly biased by strong mechanisms of social control and social desirability enhanced by the rain-dance ritual of campaigning, and does not involve the voter in informational or other costs.

Voting is one among a repertoire of political actions. However, for many, elections are ‘the defining feature of the democratic process. They are the critical juncture where individuals take stock of their various political attitudes and preferences and transform them into a single vote choice’ (Dalton and Weldon, 2005, 4). Voting is the most common and important political activity that citizens engage in. Milner (2010, 77) calculates that voting is about four times as common as any other electoral form of participation and much more common than any non-electoral form of activity. Thus, for the vast majority of citizens political participation constitutes voting in elections. Given that many citizens pay very little attention to politics in between elections, elections also play an important educational role. In the weeks or months surrounding a campaign ‘people are educated about the issues facing the country’ (Butler, 1995, 124). Clearly voting is not the only measure of political engagement and not always the best gauge of a healthy democracy. However, voter turnout remains the best, albeit imperfect ‘thermometer we have to measure the health of the body politic’ (Milner 2010, 78). If, as is often said, democracy is inconceivable without political parties, then democracy is impossible without voting. This is a theme that I return to in Part III.

Because elections mobilize a broad section of the population, elections also serve to iron out some of the participatory inequalities that characterize other forms of political participation. Voting serves as an equalizing device because almost everyone has the right to vote and no vote, in a basic sense, is worth more than another. As Verba et al. (1995, 12) argue: ‘All democracies use elections as a great simplifying mechanism for dealing with the problem of political equality.’ Accordingly, voters have been found to be relatively representative of the population, much more so than for other forms of political participation (see Verba et al., 1995, 512). This means that the people’s ‘voice’ as expressed through elections is much less biased than is the ‘voice’ of the people as expressed through other more demanding forms of activity that I cover in Part III of this book. This is one of the most important reasons why we should be concerned about turnout decline.

It has also been proven empirically that it matters who votes. Burnham (1987, 99) remarked that ‘the old saw remains profoundly true: if you do not vote you do not count’ (cited in Lijphart, 1997, 5; see also Green and Shachar, 2000, 570). Wattenberg (2002, 98) comments that ‘as long as young people have low rates of participation in the electoral process, they should expect to be getting relatively little of whatever there is to get from government’ and that until young people start showing up in greater numbers in the polls ‘there will be little incentive for politicians to focus on programmes that will help them.’ Intuitively the above statements seem to be true: Do not vote and you will be ignored seems to reflect the conventional wisdom. But what is the empirical evidence to support this? Dalton (2011a, 9) argues that if young people participated at a higher level in the 2000 and 2004 US elections the election results would have been reversed and it would be hard to argue that that would not have changed the direction of the country. Other studies that have concentrated on young people have confirmed these findings. Wattenberg’s analysis of the 2000 US election shows that had young people turned out at a higher rate they would have influenced the outcome as they would have the outcome of the 1994 mid-term election, leading Wattenberg (2002, 118) to conclude that ‘who votes does make a difference.’ Research in Britain on the effect of non-registrants following the introduction of the poll tax showed that those who failed to register to vote (many of whom were young) could have changed the outcome of the narrow Conservative party victory in 1992 (Dorling et al., 1996, 37). All of this suggests that non-voters are different from voters and that their lack of participation has real effects on political outcomes.

Background: generational and lifecycle effects

As stated in the introduction we need to examine political engagement in light of two effects (i.e. lifecycle and generational). Lifecycle effects see little aggregate change over time whereas generational effects should be viewed much more seriously as it could mean, for example, that non-voters may eventually come to replace regular voters. Studies have found evidence of generational declines in turnout among the young. The most comprehensive study of generational effects, The New American Voter, concluded that ‘Generational replacement has been a dominant source of change in participation in voting turnout for the electorate as a whole’ (Miller and Shanks, 1996, 510). Generational effects have also been found in Britain (Clarke et al., 2004, 269) and Canada (Blais et al., 2004, 227; Blais and Loewen, 2011, 17).1 Thus, the research suggests that young people are turning out at the polls in lower and lower numbers over time.

Other research supports these findings. Research shows that voting is a habit that if not acquired early on is less likely to be acquired in later years, as the lifecycle effect would predict, and attributes a large part of the generational change in turnout to voting not becoming a habit in the early years. Mark Franklin (2004, 12) argues that voting is a habit that most acquire early and ‘those who find reason to vote in one of the first elections in which they are eligible generally continue to vote in subsequent elections, even less important ones’ (see also Stolle and Hooghe, 2005, 158). In this sense, the past leaves a ‘footprint’ in subsequent elections that reflects the low turnout of an earlier period (Franklin, 2004, 43). Plutzer (2002, 43) also found that ‘A citizen’s voting history is a powerful predictor of future behaviour.’ Green and Shachar (2000) have called this ‘consuetude.’ Consuetude refers to their finding that ‘merely going to the polls increases one’s chance of returning’ even after a host of individual factors that typically predict turnout are controlled for (Green and Shachar, 2000, 562).

If confirmed, this accumulated evidence of generational effects has some troubling consequences. If young people fail to acquire the habit of voting then a new generation of non-voters will eventually come to replace older regular voters. While the effect might be marginal at first this will accumulate over time and ‘will continue until the new rate of voting is reflected throughout the electorate—a development that could take as much as fifty years to run its course’ (Franklin, 2004, 12–13). Franklin (2004, 12–13) predicts that this could translate into a 12.5 per cent decline over 50 years noting that ‘turnout might be undergoing substantial long-term decline in many established democracies.’ This could have serious consequences. In regards to the US Zukin et al. (2006, viii) argue: ‘that sizeable portions of two successive generations have now opted out of electoral political life portends a less attentive citizenry and potentially dire consequences for the quality of our democracy.’ The same could be said for all the Anglo-American democracies if the findings above are confirmed. In the sections below I examine turnout among the young which will tell us how alarmed we should be in regards to generational and lifecycle effects.

The data: voter turnout among the young

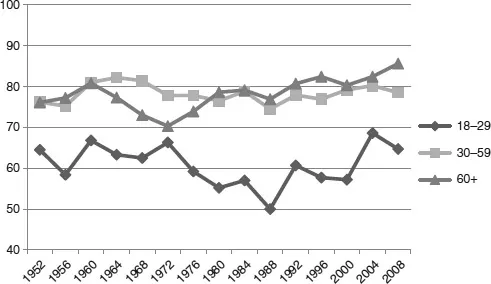

In this section I examine turnout among the young using across-time data. It is widely known that age is the best predictor of turnout (Norris, 2002, 89; Blais et al., 2004, 222) and almost all studies find turnout to be lowest among the young (Adsett, 2003, 247; Phelps, 2005, 482; Rawnsley, 2005, 2; Fieldhouse et al., 2007). It is therefore reasonable to expect that turnout will be lower among the young in the analysis below. But to what extent requires greater investigation. Furthermore, it is important to understand (in relation to lifecycle and generational effects) how this has changed over time and how this differs by country. Figures 1.1–1.4 show reported turnout over time using each country’s respective national election study. The figures show reported turnout over time among three age groups (18–29, 30–59 and 60+).

Using the American National Election Study (ANES) data Figure 1.1 shows the percentage of Americans who voted between 1952 and 2008 by age. In Figure 1.1 we can see that turnout has remained quite high among the middle-aged and older age groups. Among the middle-aged turnout has never fallen below 75 per cent. Among the older Americans turnout has never fallen below 70 per cent. With the exception of 1968 and 1972, when turnout was lower among older people, turnout has remained consistently high for both of these age groups. The picture is very different for young people. Turnout among the young is much more volatile than it is for older people. However, turnout among the young is not in secular decline. In fact, in 2008 turnout is higher (by a small margin) among the young than it was at the beginning of the time series in 1952.

It is worth considering young people’s volatile voting patterns in light of history. To begin, we can see turnout did increase among the young in the 1960 Kennedy/Nixon election which is to be expected given Kennedy’s youthfulness and his ‘changing of the guard’ appeal, and the closeness of the election. Turnout then fell in 1964 and recovered somewhat in 1972. But after 1972 turnout is very volatile among the young. This is also the period in which the voting age was reduced to 18 which may have had the

Figure 1.1 Voter turnout in the US (1952–2008) (source: American National Election Study).

Note

For question wording changes see www.electionstudies.org/nesguide/toptable/tab6a_2.htm. For the 1952–1968 period the voting age was 21 (therefore the first age category is 21–29 in this period).

effect of driving down turnout in some elections following the introduction of this law (see Franklin, 2004). Turnout falls precipitously from 1972 to 1988. It reaches a low point of 50 per cent in 1988. It then recovers in 1992 probably owing to a combination of Clinton’s youthfulness, charisma and youth outreach, a long period of Republican dominance coming to an end as well as a third party candidate (although on the latter point third-party candidates do not seem to have mobilized greater numbers of young people to vote in the 1980 and 1996 elections). Turnout declines slightly in 1996 and again in 2000 and then increases sharply in 2004 (perhaps because the ‘voting doesn’t matter’ stigma was removed following the 2000 election result).

The ANES then registers a fall in turnout among the young in 2008. This finding should be treated cautiously. The question wording for the turnout question was changed for some of the ANES sample in 2008 by which respondents were primed with different statements in an attempt to get a more honest answer from them about whether they voted or not. This could have made the young more likely to answer the question honestly whereas for older groups (who are more likely to have actually voted) it had a smaller effect. Other evidence that is more comparable across time suggests that voter turnout among the young increased in 2008, even after higher turnout among the young in 2004 (CIRCLE, 2008; Falcone, 2008; Milner, 2010, 89). Higher turnout among the young in 2008 also refutes Franklin’s (2004) argument that the closeness of the election will have a large effect on turnout given that the 2008 election was not a particularly close one.

Figure 1.1 shows that turnout among the young is not in secular decline. However, over the time series we can see a larger age gap between the young and old opening up. For example, in 1952 there was an 11 percentage point difference between the young and old. This gap expands to a high point of 27 in 1988 and at the end of the time series in 2008 has closed to 21 percentage points.2 This is much larger than the average gap in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Thus, it is in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s that larger gaps have opened up (especially in the 1980s and 1990s). Although young people have always been less likely to vote than older people this trend has become more pronounced over time. This should be concerning and suggests that young people are becoming less likely to vote over time as compared to older people, providing some support for the findings of generation...