![]()

Part I

Conceptualizing the

EU diplomatic system

![]()

1 The diplomatic system

of a non-state actor

Introduction: a journey into a conceptual puzzle

This chapter invites the reader on a journey into the central concepts upon which this research is based. Diplomacy, European foreign policy, international organization and international bureaucracy all represent autonomous fields of study that partially overlap. These concepts offer intersecting theoretical puzzles which are crying out to be disentangled. While this book does not pretend to take on this ambitious task, it cannot avoid introducing these contiguous fields of analysis and locating itself in the study of the diplomatic activities of a non-state entity – a field that crosses boundaries.

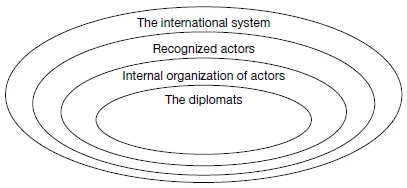

The chapter starts by reviewing those features and evolutions of diplomacy that help us locate the diplomatic model embodied by the European Union (EU). The first section offers a definition of diplomacy and attempts to grasp the evolutionary character of the institution of diplomacy by focusing on the question: who is entitled to play the diplomatic game? It presents an analytical framework for the study of diplomacy on four levels. These are the international level; the actors entitled to play the diplomatic game; their internal organization; and the diplomats – those people who speak and act on behalf of the entity they represent. A conceptual framework is presented for each level.

This analytical grid informs the chapter and the entire book. This chapter focuses on the first and second conceptual levels and introduces the fourth. Chapters 2, 3, 4 and 7 look at the third level in more depth; and Chapters 5 and 6 at the fourth level. To grasp the second level of analysis, this chapter explores the link between diplomacy and the collective foreign policy pursued in the framework of the EU. Complementing this analytical process, I also introduce the concept of meta-diplomacy to describe the way in which European foreign policy-making is supported. This concept depicts a corporate system that relies on a continuous process of negotiation in order to achieve a common foreign policy. The chapter then introduces the puzzle of the EU’s international identity before focusing on the people who actually practise diplomacy: the diplomats. Finally, it offers some general conclusions.

Diplomacy: definitions and levels of analysis

Defining diplomacy is a particularly difficult task, due to both its specificity and its notorious trickiness (Sharp, 2003: 857). It can be defined as a ‘method of political interaction at the international level and the techniques used to carry out political relations across international boundaries’ (Plischke, 1979, in Leguey-Feilleux, 2009: 1). This definition sheds light on both the polyvalence and the multi-dimensionality of the concept of diplomacy. The relational nature of diplomacy (which is expressed in political interaction), the environment in which these interactions occur (the international level) and the tools necessary to play the diplomatic game (specific techniques and organizational structures) all converge in this definition and make for plural interpretations.

First, diplomacy is a relational concept. It implies the existence of a Self (Faizullaev, 2006) and entails the concept of Otherness (Sharp, 2009: 40). As with all relational concepts, diplomacy possesses features related to both the international structure and to the agents that interplay within this structure. Structure and agency components are mutually constitutive and contribute to the process of definition and redefinition of a diplomatic regime over time. The term ‘structural components’ refers to the characteristics of an international system. In this context, the term ‘diplomacy’ has been used to indicate an institution,1 a central feature of the international system,2 ‘symbolizing the existence of the society of states’ (Bull, 1977: 172). Internal components relate to the nature and institutional organization of actors entitled to play the diplomatic game in a given period. Thus, diplomacy has been defined as a constitutive element of statehood,3 an indicator of states’ leverage, influence and power in the international system,4 and an organizational principle and feature of Ministries of Foreign Affairs and of executive power.5 As a means to an end, it has been defined as an instrument of foreign policy,6 as a modality of interaction7 and as a technique whose main functions are ‘information, negotiation and communication’8 and ‘minimization of the effects of friction’.9

This group of definitions reveals that the polyvalence of the term is coupled with intrinsic multidimensionality. The term diplomacy contains four main analytical dimensions: the first related to the nature of the international society under enquiry; the second depicting the physiognomy of actors who are entitled to play the diplomatic game on the basis of reciprocal recognition; the third touching upon the internal organization of the actors entitled to play the diplomatic game; and the fourth concentrating on the actual people who play the diplomatic game on behalf of their states/organizations.

Figure 1.1 The multidimensionality of the concept of diplomacy: from systems to entities, from entities to people

The first dimension describes the main characteristics of the international environment in which diplomatic exchanges take place. As an attribute of a given system over history, diplomacy has been widely conceived as a constitutive institution of the global international society (Bull, 1977; Attinà, 1979; Wight, 1979). As an institution, diplomacy bears ‘a relatively stable collection of practices and rules defining appropriate behaviour for specific groups of actors in specific situations’ (Buzan, 2004: 165). It reflects the structure of a given international system as perceived and organized by those international actors who mutually recognize themselves as entitled legally to act at the international level. Diplomacy, in other words, is an organizing principle produced by a negotiated system of interactions. From this perspective, Liverani defined diplomacy as ‘the product of an international community of mutually independent polities, whose long-lasting and rather intensive contacts generated precise norms regulating their interactions’ (Liverani, 2000: 26; emphasis added). Hence diplomacy regiments relations among international actors on the basis of a body of formal and informal norms, which reflects entrenched assumptions about the foundations of the international order. As a prerequisite for agency, the condition that underpins any diplomatic system is ‘required and accepted interdependence’ (Lafont, 2001: 41). Therefore, only those actors who mutually recognize themselves as satisfying some given requirements can enter the diplomatic arena.10

In each historical context the criteria for accession agreed upon by members of a given system determine the subjects entitled to play the diplomatic game. ‘[I]n the sense of the ordered conduct of relations between one group of human beings and another group alien to themselves’, diplomacy ‘is far older than history’ (Nicolson, 1939: 17). This endurance is a widely recognized feature of diplomacy that has caused some commentators to talk of its inherent inertia (Kleiner, 2008). Endurance, however, does not equate to immutability. During its long evolution, diplomacy has been characterized by the ‘twin processes of conservation and change’ in a ‘complex ecology of conduct produced by civilization over a long period’ (Cohen, 2001: 30, 36).

The second dimension identifies the actors who are entitled to play the diplomatic game in a given period. Historically, diplomacy has not always been associated with either statehood or sovereignty. This prompts us to focus on the physiognomy of the actors who are allowed to play the diplomatic game. The definition of the core attributes of actors explains the kind of diplomatic activity that they can perform effectively. The second dimension also embodies definitions of diplomacy as a ‘means to an end’. In this context, diplomacy is defined as an instrument of foreign policy, an instrument of representation, a method whose main functions are ‘information, negotiation and communication’ (Wight, 1979: 115–17). In light of the binary relationship betwesen diplomacy and foreign policy, the definition of the former is largely shaped by that of the latter, whether that definition is wide or narrow. As will be explored in depth, different diplomatic games exist, based on any given actor’s capacity to act.

The third dimension focuses on the organizational features and institutional arrangements of the subjects entitled to play the diplomatic game in a given period. This dimension rests on three binary relationships that contribute to the definition of diplomacy: the distinction between an ‘inside’ and an ‘outside’, where separateness and the need to communicate are two fundamental qualities of diplomacy (Hocking, 2005: 3); the relationship between the executive and the Foreign Ministry (decision-making level) and embassies on the spot; and the relationship between the entity to be represented and the bodies predisposed to represent it.

The fourth dimension is less abstract and focuses on the people who actually conduct the diplomatic game on behalf of the entity that they represent: the diplomats. This level of analysis reminds us that, ‘figuratively speaking, diplomatic negotiation is a process where the comparatively “small selves” of diplomats mediate between the “larger selves” of states’ (Faizullaev, 2006: 513). Diplomats are representatives of a bigger entity and constitute the voice and face of the entity they represent abroad. On the one hand, they are representatives of the entity to which they belong. On the other, some special characteristics stem from their peculiar professional status, which has been regarded as constituting an ‘exclusive fraternity’ (Cohen, 1991: 3). On the basis of this taxonomy, this book will refer throughout to a given level in order to clarify in what sense the term diplomacy is used.

Who is entitled to play the diplomatic game?

Three main criteria come into play when answering the question: ‘who is entitled to play the diplomatic game?’ These are ontological, formal–legal and reputational criteria. Ontology relates to ‘being, to what exists’ (Hay, 2002: 61). In a world like that of diplomacy, the criteria for existence are based on the criteria for admission on to the diplomatic dance floor. In this context, ontological criteria posit that ‘what “exists” is exactly that which can be represented’ (Gruber, 1993: 19). This definition, borrowed from knowledge-based systems, fits the world of diplomacy well insofar as the actors’ existential requirements, stemming for instance from sovereignty, bring about a capacity for existence in the diplomatic arena.

Formal–legal criteria relate to the definition and scope of action of a given international legal person. International Legal Personality (ILP) defines the legal wherewithal to act under the umbrella of international law. In diplomatic terms, it also determines the jus legationis, which defines ‘who has the capacity to send embassies and messages representative of his thought’ (Constantinou, 1996: 3).11

Finally, reputational criteria are based both on reputation and functional utility. To quote a topical example, a non-governmental organization (NGO) that might be considered useful in the negotiation of a bilateral agreement will not automatically satisfy the criteria necessary for entry into the diplomatic arena. In consequence, some actors play an ‘ancillary’ and functional diplomatic role.

All these criteria can be applied diachronically to different historical diplomatic eras and help define criteria for agency and the scope of action of different diplomatic actors. Historically, diplomatic practices existed among different entities on the basis of reciprocal recognition of legitimacy (whether among empires, kingdoms or cities) long before the emergence of states. According to Cohen (2001: 23), the Mesopotamian, the classical Greek and the Roman all constitute the continuous ‘Great Tradition’ of diplomacy in the ancient world, consisting of ‘a body of ideas, norms, practices and rules governing relations between political entities, usually, but not always, sovereign authorities’.12 The breeding ground for a diplomatic culture can also be found in fifteenth-century medieval Europe. The seeds of a common diplomatic tradition sprang into life from a perceived sense of the unity of Latin Christendom (Mattingly, 1955: 16) and developed throughout the late Dark Ages around ‘three converging currents of tradition: ecclesiastical, feudal, and imperial, or, if one prefers, Christian, German, and Roman, embodied in canon law, customary law, and civil law’ (Mattingly, 1955: 19). Therefore, until the seventeenth century, ‘“the real world”, at least in terms of diplomacy, was still limited to the tiny peninsula at the Western end of the Eurasian mass called Europe’ (Roosen, 1976: 9). These features contributed to the consolidation of a rudimentary European diplomatic tradition, which reflected ‘a hierarchically ordered universe … of partial and overlapping sovereignties’ (Mattingly, 1955: 24). In the Dark Ages, the problem of circumscribing diplomatic principals was, both theoretically and practically, a fictitious one, as diplomatic practices were scattered among different subjects according to the make-up of medieval European society (Mattingly, 1955: 24). Consequently, diplomatic exchanges occurred between princes, a term which was generally attributed to ‘the kings, emperors, dukes, etc., who were sovereign rulers, or at least, those who were allowed to send diplomatic representatives to other rulers’ (Roosen, 1976: 6). To stretch a generalization, in pre-modern societies the criteria for entering the diplomatic arena were therefore based on hierarchy, recognition and reputation, whereby some entities acknowledged the necessity of communicating safely with both friends and enemies. Recognition did not necessarily rest on the legal criteria typical of the modern period.

In the modern period diplomacy became deeply interwoven with statehood (Poggi, 1990: 18). Modern states emerged ‘to fill the vacuum created by the extinction of the supreme authority of Emperor and Pope’ (Gross, 1948: 26). They represented a new system of organizing the political space and disciplining relationships between peers (Mattingly, 1955: 66). One effect of the defeat of imperial power and the Church’s secular state was that the Treaty of Westphalia (1648) recognized ‘a new type of dominant unit, the sovereign, territorial State, and a distinctive form of international society associated with that unit’ (Buzan and Little, 1999: 90). The sovereign state model can be summed up as ‘a system of political authority based on territory, mutual recognition, autonomy and control’ (Krasner, 2001: 17). Distinctively, Westphalia redesigned the borders of the system of rules into ‘territorially defined, fixed, and mutually exclusive enclaves of legitimate dominion … based on two fundamental spatial demarcations: between public and private realms and between internal and external realms’ (Ruggie, 1993: 151).

Sovereignty, therefore, possesses both internal and external components: ‘internal sovereignty refers to a state’s ability to exercise de facto political control over its territory, external sovereignty to its recognition as a de jure member of the society of states’ (Wendt, 2004: 294). At the international level, Westphalia codified the ‘application of the principle of the balance of power on a large scale’ and an ‘operation of the maxim partager pour équilibrer’ (Gross, 1948: 27). From this perspective, rather than a ‘mechanical consequence of the state of anarchy’, the balance of power consisted of ‘a recognized social practice, and a shared value [consisting of] alliances, guarantees, neutrality …, great power management … and also war, again, … understood as a social practice’ (Buzan, 2004: 281). Henceforth, Westphalia reflected the state of peace as agreed by the new dominant units and posited the necessity of defending the new order against any possible challenger. From an ontological perspective, state primacy is deeply entwined with the monopoly on the use of force, ‘expressed in the sovereign right to make war’ (Ruggie, 1993: 151). Therefore, despite the fact that diplomacy could be conceived in terms of opposition to war, in modern thinking both diplomacy and war are interwoven in the Westphalian definition of sovereignty. They both emanate from the ‘institutionalization of political power’ (Poggi, 1990: 18). Thus, these instruments belong to the subjects entitled to play the full game of international relations. Both political choices can be defined as means to an end: ‘product[s] of civilization, outcome[s] of an organized effort’ (Aron, 2003: 364). As an expression of the sovereign state model, the Westphalian legal order defined an exclusive relationship between the state and the law (Cutler, 2001: 134), in determining a ‘mechanism of exclusion’ for all subjects other than the state. In other words, the concept of states’ sovereignty has allowed states ‘not simply to have ultimate authority over things political; [but to] have the authority to relegate activities, issues, and practices to the economic, social, cultural, and scientific realms of authority or to the states’ own realm – the political’ (Thomson, 1995: 214). In modern conceptions, states are ontologically the only actors entitled to play the diplomatic game. The main ontological criterion which defines their existence in the diplomatic arena is proforma sovereignty,13 whereas de facto qualities define the differing levels of leverage and reputation of states. In the case of states, their legal capacity to act, as with their ILP, is full and automatic (Frid, 1995: 13).

External and internal sets of causes have progressively brought about a shift to a post-Westphalian diplomatic order, in which the monopoly of states over key resources has been eroded. Breaches in the constitutive elements of states have been seen as an effect of the dismantling of three logical fictions: the separation of the economic from the political (Strange, 1995; Held, 1997); the separation of the nation from the state (Habermas, 1998; Guéhenno; 1995); and the distinction between the national and the international (Wallace, 1999; March and Olsen, 1998). Structural change in the global political economy engendered the emergence of a new model of...