![]()

1 Introduction and definition of sovereign wealth funds

Introduction

The term sovereign wealth fund (SWF), referring to a state-owned investment fund composed of financial assets including properties, stocks and bonds, was coined in 2005 by Andrew Rozanov, a financial analyst from the City of London. SWFs have recently raised attention in the global financial system, as they have highlighted the increasing financial power of governments in comparison with private financial institutions within the international economic structure.

This controversy was further triggered by the size of the assets under management (AUM) of these funds. In May of 2007, Morgan Stanley published a report on the estimated size of SWFs and predicted that the AUM of the funds would grow from the estimated 2007 figure of US$2.5 trillion to double that size before 2010, and reach around $12 trillion by 2015 (Jen, 2007).

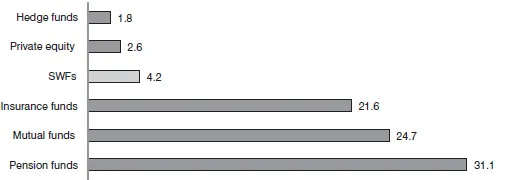

The Morgan Stanley forecast was proven to be less plausible in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008. Like many other investment institutions, the portfolio of investments of the SWFs was affected by the financial crisis. Most of these funds recorded significant losses in the value of their assets. Deutsche Bank predicted that by 2019 total assets under SWF’s management are likely to amount to US$7 trillion, which was more than twice the volume of those assets in 2010 (Kern, 2010). A study by International Financial Services London (IFSL) in 2010 reported that the SWFs were about 2.5 times bigger than hedge funds and their assets stood about US$1.2 trillion above the AUM of private equity funds (see Figure 1.1). Despite the impact of the global financial crisis, the SWFs are expected to gain more power in international financial markets, and their portfolio of assets is predicted to grow more in the decades to come.

Definition

The SWFs are not the only type of government-owned investment institution. There has been a debate amongst financial analysts, as well as academics, on the definition of the SWFs. Here some of the definitions provided by various sources will be reviewed.

Figure 1.1 Total AUM of global investment funds ($ trillion)

Source: TheCityUK, (2011)

In 2005, Andrew Rozanov defined the SWF funds as:

…by-products of national budget surpluses, accumulated over years due to favourable macroeconomic, trade and fiscal positions, coupled with long term budget planning and spending restraint. Usually these funds are set up with one or more of the following objectives: insulate the budget and economy from excess volatility in revenues, help monetary authorities sterilise unwanted liquidity, build up savings for future generations, or use the money for economic and social development.

In 2008, the International Working Group of SWFs, established by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in cooperation with the fund’s managers to review the operation of the funds and propose a voluntary code for best practice of the SWFs, defined the SWFs to be the

… special purpose investment funds or arrangements that are owned by the general government. Created by the general government for macroeconomic purposes, SWFs hold, manage, or administer assets to achieve financial objectives, and employ a set of investment strategies that include investing in foreign financial assets. SWFs have diverse legal, institutional, and governance structures. They are a heterogeneous group, comprising fiscal stabilization funds, savings funds, reserve investment corporations, development funds, and pension reserve funds without explicit pension liabilities.

The Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, a research institute monitoring the SWFs, defines these funds as:

… (state-owned investment funds) or entity that is commonly established from balance of payments surpluses, official foreign currency operations, the proceeds of privatizations, fiscal surpluses, and/or receipts resulting from commodity exports. The definition of sovereign wealth funds exclude, among other things, foreign currency reserve assets held by monetary authorities for the traditional balance of payments or monetary policy purposes, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in the traditional sense, government-employee pension funds, or assets managed for the benefit of individuals. Some funds also invest indirectly in domestic state-owned enterprises. In addition, they tend to prefer returns over liquidity, thus they have a higher risk tolerance than traditional foreign exchange reserves.

(http://www.swfinstitute.org/fund/what-is-a-swf/)

This study defines the SWFs as institutional investors, which have some (or in some cases all) of the characteristics that are listed below:

1 Owned and financed by their respective governments.

2 Often, but not always, managed by separate organizations than the central banks.

3 Financed from the government surplus revenue (after planned government spending and/or off-budget expenditures are paid from the government commodity or non-commodity export incomes, the surplus is deposited in the SWF’s account).

4 Aim to protect the national economy from income volatility.

5 Sterilize the national monetary system from surplus liquidity to control inflationary effects of surplus liquidity.

6 Accumulate assets for future generations.

7 Diversify the government incomes from oil sector.

8 Use the surplus incomes to transfer new technologies and expertise to support economic and social development.

9 Often, but not always, holding highly diversified portfolio of investments in income generating assets spread across the world.

As noted above, the source of assets of the SWFs is the surplus revenue of their sponsoring government. The major difference between the commodity and non-commodity SWFs is the source of their assets. While the commodity-rich governments finance the SWFs from their surplus commodity export income, the non-commodity SWFs are financed from the surplus of non-commodity export income. The main focus of this study is to review the commodity-based SWFs. In order to provide a better understanding for commodity-based funds, few key characteristics of the commodity-based SWFs are reviewed below.

Commodity-based SWFs have a higher risk appetite in comparison with those that are sponsored by surplus non-commodity export income. Given the global demand for commodities, particularly hydrocarbon resources, the oil exporting countries are fairly certain that their natural reserves can generate significant revenue for the foreseeable future. The non-commodity funds rely on surplus income from the export of goods, which may not necessarily have an increasing global demand even in the short to medium term. Therefore, the continuous inflow of oil export revenue driven by global energy demand has made the oil exporting countries less concerned about the investment risks they take when investing their petrodollars.

In addition, the governance and management of most of the commodity-based funds are highly influenced by the ruling power of their sponsoring governments. Finally, the commodity-based funds tend to have long investment horizons. Again, this is as a result of the reliance of their sponsoring sovereigns on commodity export income to finance the SWFs. It is widely assumed that the source of generating surplus revenue in oil-rich countries is more sustainable than in countries with high non-commodity export revenue. Therefore, increasing oil prices and high global demand for energy allows the governments of oil producing countries to apply longer investment strategies for their SWFs.

Differentiating SWFs from other types of government-owned assets

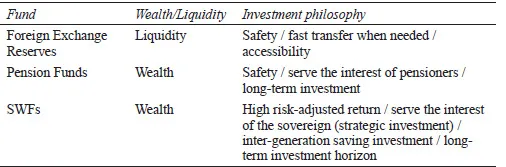

As noted above, one of the core elements of the debate over the SWFs was the definition of these funds. To draw a distinction between SWFs and other types of government assets (i.e. foreign exchange reserve funds and public pension funds), a brief review of all the three types of state-owned assets is provided below.

Foreign exchange reserves

Foreign exchange reserves are public investment funds, which are financed by the government from fiscal surpluses for economic stabilization purposes, held and managed by central banks (Mitchell et al., 2008). The main purposes of these funds are to maintain currency value, inflation and overall national financial stability at the time of possible economic uncertainties. Traditionally countries with sizeable natural resources (where a major share of the government budget is financed by commodity income) establish such funds in order to secure their national economy against the volatility of commodity markets as well as to protect the national currency against devaluation.

There are various reasons for holding foreign exchange reserves. Since the Asian financial crisis of the late 90s, in order to maintain their domestic monetary stability, most of the emerging economies have implemented a combination of policies, which include large holdings of foreign exchange reserves as well as a mixed exchange rate (Rauh, 2007). The latter has been as a result of the fixed exchange rate regime of nearly all the economies originating the major international financial crises since 1994 (Mexico in 1994, South Asia in 1997, Russia and Brazil in 1998, Argentina and Turkey in 2000). The experience of those economies has proven that without fixed exchange rates there would have not been as severe economic outcomes in the aftermath of the crisis as was the case in the presence of fixed exchange rate policies. China is a perfect example for the application of such a policy combination, by slowly allowing more financial integration and perhaps, in the coming future, more exchange rate flexibility, whilst accumulating massive foreign reserves (Jin et al., 2005). Commodity exporting economies have also had, more or less, the same pattern in place. Most of the oil-rich countries have foreign exchange saving policies in order to maintain their economic growth at the time of oil shocks. The foreign exchange reserves of those countries are primarily held in liquid assets such as short-term securities and foreign bank deposits, which can be easily transferred to their country of origin at the time of a financial crisis.

The size of these assets varies in each case. There are various ways to calculate a minimum required asset holding in the foreign exchange reserves in order to adequately insure against possible shocks (US Treasury Department, 2005). The most common view is for each country to save sufficient foreign reserves to cover three months worth of the country’s import revenue (Johnson-Calari and Rietveld, 2008). The key dissimilarity between the foreign exchange reserves and SWFs does indeed come from the purpose of holding of these assets. In other words, foreign exchange reserves are not held as a nation’s wealth; instead, they are sources of liquidity, which are often kept by the government outside their contry of origin to be transferred over a short period to protect the domestic economy from potential financial shocks should the government need to do so.1 China, Japan, Taiwan and Russia hold the biggest reserves of the kind (Hua, 2007).

Public pension funds

Public pension funds are government-owned funds, which are kept to alleviate the effects of demographic disequilibrium on the balance of the social security system. Over the last fifty years, many countries in the world have experienced sliding fertility rates and growing life expectancies. In Asia alone , the number of people over 65 will be over 500 million by 2050 (Bloom et al., 2006). This is mainly as a result of Japan’s low fertility rates and small share of immigration and China’s one child policy during the past twenty years, which has remarkably reduced birth rates in the country (Mitchell et al., 2008). Public pension funds, therefore, are state-owned investment institutions, which are created specifically to control the negative impacts of such demographic disequilibrium.

These funds are traditionally created either through an explicit fund being allocated by the government into a separate state-owned account, or as a result of excess contributions from the people of a particular age group in the government saving scheme during a demographic transition (Mitchell and Hsin, 1994). In contrast with foreign exchange reserves, pension funds are not constrained by a need for immediate liquidity. One can argue that even though the pension funds have certain liabilities, that is, to serve the interest of the pensioners, they count as national wealth. Therefore, due to their long-term liabilities, pension funds usually invest in their domestic currencies with long-term investment horizons.

Pension funds are often financed by individual pension contributions, rather than other methods of states fund collections such as taxes, privatization proceeds or surplus export revenue. Therefore, in practice current and/or future retirees are somehow considered the owners of the accumulated wealth in pension funds rather than the state. The Japanese public pension fund, with over 900 billion US$, is the world’s biggest pension fund. The California Public Employees’ Retirement System and Korea’s National Pension fund are other examples of public pension funds (Bloom et al., 2006).

SWFs

Another type of government-owned institutional investment is SWF. The SWFs can be held to serve different purposes including: balance of payment stabilization caused by a government’s export income fluctuation (somewhat similiar to foreign exchange reserves), saving for future generations, and transfer of technology and know-how for the development and diversification of the domestic economy from commodity export income (in the case of commodity-rich countries). SWFs are usually funded from surplus government income and often held outside their country of origin. In order to protect the sovereign wealth, in most cases, SWFs are managed separately from other types of public investment funds. As SWFs do not hold specific short-to medium-term liabilities, unlike pension funds and government’s foreign exchange reserves, they often invest in assets with relatively higher investment risks and have longer investment horizons than other types of government funds.

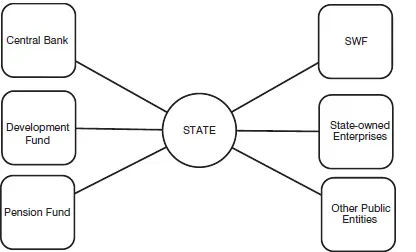

As noted, separate government bodies often manage the SWFs; however, the sovereign wealth management institutions function in cooperation with other government financial institutions in order to serve the government’s monetary and financial purposes (Kern, 2008; see Figure 1.2). Table 1.1 summarizes the fundamental differences between the three types of government funds.

Commodity-based SWFs

Based on the source of assets, the SWFs fall into two categories: commodity-based and non-commodity funds. While commodity-based funds are funded by excess revenue from the export of natural resources, non-commodity SWFs are usually funded by governments’ surplus income from the export of non-commodities. Both types of SWFs are established to serve similar monetary purposes as discussed above: fiscal stabilization, intergeneration saving and balance of payment sterilization. The different source of funding of commodity-based and non-commodity SWFs creates a number of other dissimilarities between the two groups:

• The commodity-based SWFs (CSWFs) are financed by hydrocarbon exports, therefore constitute net financial savings. In contrast, the non-commodity SWFs are by-products of controlled exchange rate policies and financed from excess monetary reserves.

• The growth of assets of CSWFs is directly related to the price of oil; while the increase of assets of non-commodity SWFs is directly linked with the increase of local currency debt (Rozanov, 2009).

• AUM of non-commodity SWFs do not represent net national savings. CSWFs, on the other hand, do represent net government savings.

• Non-commodity SWFs invest a significant share of their portfolios in commodities while the CSWFs do not, although the CSWFs of the Gulf countries have shown interest in investment in commodities other than oil and gas and included agribusiness investments in their portfolio.

Figure 1.2 State-operated financial institutions

Source: Steffen Kern (2008)

Table 1.1 Summary of government funds

CSWFs are often recognized as a crucial element in the govern...