- 196 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book addresses issues in the current literature on corporate finance using historical evidence. In particular it looks at the role of universal banks in relaxing the credit constraints of firms, supervising managers and stabilizing share prices. The key issues is whether the Anglo-American asset based financing is more efective than the main-b

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Role of Banks in Monitoring Firms by Elisabeth Paulet in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

AGENCY THEORY AND MONITORING

A theoretical and empirical interpretation

For French business, whether medium or ‘big’, the obsession with independence vis à vis the lender (the bank) was constant. It was with reference to the level of their current bank accounts that the Schneiders of the nineteenth century, for example, calculated their degree of independence and their room for manoeuvre…. The domination of banks over business, if it existed was not achieved without resistance.1

Bouvier (1988:109)

1.1 INTRODUCTION

In this chapter the basic concepts of agency and signalling theories applied to the financing of the firm are presented. In particular the chapter will study how a debt-equity contract is defined between the manager of a firm, the shareholders and the bank which provides liquidity.

Agency theory, although not quite new, is a part of decision theory which is currently characterised by a dynamic development. The well-known basic model of decision theory is related to a situation in which one person—the so-called decision-maker—has to make a decision as well as to bear its consequences. This assumption is often unrealistic. Therefore, in agency theory the decision-maker (the agent) and the ‘beneficiary’ of the decision (the principal) are all distinct. A typical example concerns the management of the firm: the agent, the manager of the firm, chooses an investment project. The principal—the shareholders of the firm and (or) the bank which finances the enterprise—partly support the risks involved in this investment.

Hence, the common element is the presence of at least two individuals. The first (the agent) must choose an action from a number of alternative possibilities. The action affects the welfare of both the agent and the principal. The principal has the additional function of prescribing payoff rules; that is, before the agent chooses the action, the principal determines a rule that specifies the fee to be paid to the agent as a function of the principal’s observation. The problem acquires interest only when there is uncertainty at some point and, in particular, when the information available to the participants is unequal.

As information is asymmetric between the economic agents, control is one of the main factors of agency. The second part of this chapter will be devoted to the definition of this control mechanism in order to determine which of the two principals, the shareholders of the firm or the bank with which the enterprise is involved, is able to exert effectively this monitoring role.

1.2 PRESENTATION OF THE FINANCIAL THEORIES

(a) Basic concepts of agency and signalling theories

The financial theory of agency focuses on the relationships between different groups of security holders (equity and bondholders) in the context of optimal financing of the firm. The standard economic theory of agency considers two individuals: a principal, who provides the capital, and an agent (the manager), who provides the effort. Both are assumed to be utility maximisers. Principals value end-of-period wealth which is derived from their share in the realised value of the firm. Agents value their end-of-period wealth stemming from the realised profit.

Agency problems arise because, under the behavioural assumption of self-interest, agents do not invest their best efforts unless such investment is consistent with maximising their own welfare. The agency model is basically a formulation of the principal’s problem of choosing the ‘best’ employment contract for the agent, where ‘best’ is defined in the context of Pareto optimality. A Pareto optimal contract is such that no other contract can improve the welfare of one party without reducing the welfare of the other.

Observability of the agent’s effort is really the core of the incentive problem in this theory. While the effort level determines the level of output of the firm (i.e. the end-of-period value or cash flows), the output is also affected by random events that are beyond the control of the agent. An agency problem arises when the consequences of the agent’s efforts cannot be distinguished entirely from the consequences of other random events by observing output alone. In the tradition of the agency theory, the output (payoff) level is mutually observable by the principal and the agent, but the effort level is observable only by the agent. First best contracts induce an optimal risk-sharing between agent and principal.

Further adverse selection is often introduced between the two parties. Consider an owner-manager who seeks to finance a project by selling securities, while the true nature of the return distribution of the project is unknown to the outside market. Management possesses valuable information about the project that is unavailable to the market. If this information were revealed fully to the market, the market would value the project at V. Otherwise, the market is unable to distinguish this project from another less profitable project with a value Vb. This asymmetry may be corrected, at a cost, through various ‘signalling mechanisms’. In the absence of an unambiguous signal, however, management will obtain less for securities sold than their ‘fair value’ reflected in the true nature of the project A. The difference between the ‘fair’ price and the actual price is the agency cost associated with informational asymmetry. It exists for the issuing of debt as well as new equity securities, provided that there is a differential probability of bankruptcy for the two projects. In their seminal paper, Jensen and Meckling (1976) proposed agency costs as a key tool in evaluating designs of a principal-agent relation. Agency costs were defined as the sum of:

- the monitoring expenditure by the principal;

- the bonding expenditure by the agent; and

- the residual loss, i.e. the monetary equivalent of the reduction in welfare experienced by the principal due to the divergence between the agent’s decision and ‘those decisions which would maximise the welfare of the principal’ (ibid.: 308). The agent receives compensation for his work and supports part of the agency cost (bonding expenditure).

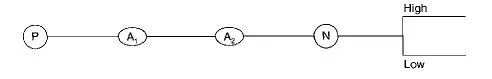

Adverse selection can be described through three categories of model. The first is represented by a situation of moral hazard with hidden action. Under moral hazard, it is easier for the principal to observe the manager’s output than his effort. The principal offers a contract to pay the agent based on output which depends on the agent’s effort. We can represent this situation by a game tree. In the model, the principal (P) offers the agent (A) a contract, which he accepts or rejects. After the agent accepts, nature (N) adds noise to the task being performed. Figure 1.1 illustrates this situation.

If the principal knows the agent’s ability but not his information level about the potential investment, the problem is moral hazard with hidden action. An example is given by F.Gjesdal (1982), whose paper considers the use of imperfect information for risk sharing and incentive purposes between bondholders and stockholders when perfect observation of actions and outcomes is impossible, making complete contracting infeasible. The incentive problem consists of two parts: the choice of information system and the design of a sharing rule based on the information in the agency problem.

Figure 1.1 Moral hazard with hidden action

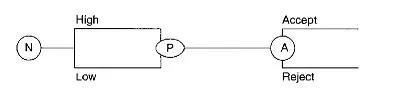

Figure 1.2 Adverse selection models

The second case concerns the largest part of the agency literature: adverse selection models. Adverse selection can be represented by Figure 1.2.

Kose and Kalay (1982) illustrate adverse selection by analysing the conflicts between two groups (stockholders and bondholders) concerning the riskiness of company projects. They derive an optimal set of contractual arrangements which minimise the cost of this conflict. In that sense, these authors come back to the idea of Myers (1977), who has argued that stockholders who control the firm could attempt to transfer wealth from the bondholders, even by rejecting profitable investment projects. In other words they can choose policies which reduce the market value of the firm. Myers has indicated that self-imposed constraints on dividend pay-outs by stockholders are a possible solution to the problem of under-investment.

The debt contract between a bank and the manager of a firm defines the adverse selection problem. According to the recent literature, such as Laffont and Freixas (1988), Gale and Hellwig (1985) and Diamond (1984), the assumption of asymmetric information leads the bank to prefer credit rationing, to an equilibrium between supply and demand at a specific interest rate. The agency relations between a bank and a firm prevent the lender from distinguishing sound creditor risks from bad ones. The requirement of a guarantee can solve such problems and enables the lender to separate good borrowers from the bad ones. In this context Deshons and Freixas (1987) establish two types of loan system:

- the optimal separating contracts, where good credit risks are identified;

- the rationing credit solution, where neither guarantee nor interest rate make the selection role possible since the bank is unable to take the surplus of its loan customers.

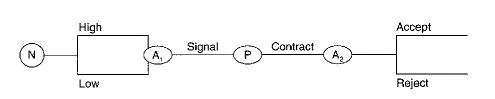

Figure 1.3 Signalling model

The latter situation, represented by Figure 1.3, is the signalling model. The agent sends a signal to the principal.

For example, the managers of firms transmit information to the shareholders and the creditors of the firm they administer. This activity of signalling has two aspects:

- the manager of a good firm sends information to the external investors to signal that the enterprise is a good firm;

- however, the manager of a bad firm might use the same signal to make investors think that the enterprise is a good one, but it is more costly for him to do so.2

A penalty system must be in place to prevent the manager of a bad firm from sending false signals. The problem of signalling in the determination of the debt level of a firm is expressed by the diversification of a security portfolio for a manager-shareholder. If the latter possesses a good productive investment, he will inform the market by the composition of his portfolio. If the project is really good, he will devote a significant part of his savings to it, to the detriment of other projects. As he is the best informed, his less diversified portfolio is a signal which can indicate the value of the project. Leland and Pyle (1977) conclude that the value of the enterprise is positively correlated to the proportion of capital held by the shareholder-manager. But the authors emphasise that this relation is a non-causal statistical relation between the value of the firm and its debt level. Every modification of the manager’s portfolio induces a change in the perception of the future liabilities by the market: it results in a new financing policy, and ultimately another value for the firm.

In this context, the level of diversification in the assets held by a firm constitutes the most valuable information as regard the value of the firm. As observed by Jensen and Meckling (1976) or Grossman and Hart (1983), if a firm does not want to be indebted, its risk of bankruptcy is limited but the market will suppose that the maximum performance for the firm has not been attained. In the opposite case, a loan from a bank increases its risk of bankruptcy, which obliges the managers to be more efficient. This argument illuminates the divergence of objectives between the different partners: the shareholders, who seek dividends, the managers, who must signal the value of their organisation by diversifying their portfolio, and the banks, which grant credit and want to avoid losses if the firm goes bankrupt.

To conclude these first two points, it seems that the application of agency and signalling theory to finance decisions is concerned with the influence of conflicts between shareholders and managers over the value of the firm, and the resolution of these conflicts by the use of debt. The latter involves an incentive scheme for performance. The debt increases the bankruptcy risk, which is a threat sufficient to encourage the manager to administer efficiently. Bankruptcy will mean for the manager not only loss of his work, but also being held responsible for the situation.

In these models, debt is defined by an optimal contract for the firm, and the optimal structure of the enterprise is a combination of debt and stocks. So, the financial parameters justifying the limits of debt policy can be deduced by analysis of the shareholders’ and managers’ points of view (e.g. level of risk of the project, expected profit, etc.). However, these theories have a certain number of limitations. In particular, the same financial indicators have specific roles in each approach. The debt level constitutes a very manipulable variable for the administration of the firm. It signals the quality of an enterprise for Ross (1977). It is the origin of the agency cost for Galai-Masulis (1976) and Jensen and Meckling (1976). The results of these analyses do not seem to be very coherent: an increase in debt or in the part attributed to the manager and shareholders in the capital induces an increase in the market value of the firm, according to the signalling models. But the difficulties due to agency relations then become more and more pronounced. Myers (1977) has taken an interest in this problem. He explains that three financial parameters must be taken into consideration at the same time: the dividend distribution, the amount of investment and the level of debt.

Agency costs appear there as one of the essential elements of a new kind of signalling model. For Myers, the existence of debt for an enterprise can generate a sub-optimal level of investment: the nature of equity and the financial structure can be modified such that the investors do not maximise the value of the firm but the value of the stocks, to the prejudice of debt.

(b) Common agency

As indicated above, agency theory aims to explain the conflicts of interest and differing information that could exist between the different partners of the firm: managers, shareholders and lenders. Every partner determines the optimal level of debt according to hi...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- FIGURES

- TABLES

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- 1. AGENCY THEORY AND MONITORING: A THEORETICAL AND EMPIRICAL INTERPRETATION

- 2. THE CRÉDIT MOBILIER AND THE FRENCH STOCK EXCHANGE 1853–1914: AN EMPIRICAL PERSPECTIVE

- 3. CORPORATE INVESTMENT, CASH FLOW AND FINANCIAL CONSTRAINTS OF FIRMS: THE CASE OF THE CRÉDIT MOBILIER

- 4. THE SUPERVISORY ROLE OF THE CRÉDIT MOBILIER: SOME INTERPRETATIONS

- 5. GENERAL CONCLUSIONS

- APPENDIX A: DATA ON THE CRÉDIT MOBILIER

- APPENDIX B: DATA RELATIVE TO THE GENERAL INDICES (GNP, SHARE PRICES) FOR FRANCE BETWEEN 1852 AND 1914

- APPENDIX C: DATA RELATIVE TO THE AFFILIATED COMPANIES

- APPENDIX D: DATA RELATIVE TO NON-AFFILIATED COMPANIES

- APPENDIX E: MONTHLY SHARE PRICES FOR AFFILIATED COMPANIES BETWEEN 1866 AND 1868

- APPENDIX F: DATA FOR INVESTMENT AND CASH FLOW TESTS

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY