![]()

1 Hamas and the Palestinians as a case study

Why should we in the world be focused on a conflict between an insurgency militia and an opposing state the size of Massachusetts with the population of Ireland? Some aspect of the Middle East Conflict between Israelis and Palestinians is in the news every day, while important problems in other parts of the world go unnoticed. The region represents the cradle of civilization and of the great religions. It is the meeting point that connects Europe and Asia, the East and the West and where the great armies of the world have waged battle directly or through proxies for over two millennia. The Middle East Conflict represents the symbolic knot of the world and is looked at as good versus evil with varied perspectives across the globe. This is why people pay attention to the problem and we should do our best to understand it from various perspectives.

So why is Hamas, a key participant in the Middle East Conflict, a privileged case that can provide understanding about insurgent groups elsewhere? The answer is surprisingly simple. It is because the world is watching. For some, Hamas is a terror group par excellence. For others, it is a model to imitate. The group is being watched by other insurgencies and states at war with insurgencies and terrorism. And, because of its place, Hamas pays attention to the other insurgent groups in the world. The group consciously takes a position to distance itself from some while aligning itself with others. Insights about this group go a long way to understanding insurgent groups elsewhere.

Even discounting the historical significance of this small area of the world, examining Hamas’s use of violence is a good case study. To begin with, this case is unique in that it is still active, so living participants of the conflict are accessible for interview, and violent acts and public statements by leaders are captured in some form of archive. There are also large archives of scientifically credible polling data over decades of the conflict which has yet to be fully grasped by the academic and policy community. This polling data includes rich information that provides a clear picture about the attitudes of Palestinians and the environmental conditions that influence Hamas’s use of violence over time. Mostly, conflict environments are void of good analyzable data for various reasons, including safety considerations, which complicates our ability to understand the dynamics involved. It is the opposite for this case. There is a ‘mountain’ of analyzable data.

The ‘Holy Land’, as it is known by Jews, Muslims and Christians, is at the epicenter of many of the goals and objectives by groups outside Palestine. The recent and ongoing tumult in the Middle East, particularly the rise and fall of the Arab Spring, the election and overthrow of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, the civil war in Syria, Hizballah’s military operations supporting Bashar al-Assad, the nuclear pursuits of Iran, the emergence of the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, and the emergence of a new Caliphate in the minds of hundreds of millions of Muslims across the globe, furthers the need to explore the implications of these influences on Hamas as it pertains to Palestinians, its core mission of the reclamation of lost lands in 1948 and its use of violence against Israel.

My willingness to go to the region and to seek out the leaders and to talk with combatants was the primary reason why the research behind the book could be conducted. In the spirit of classic anthropology and field-based scientific research, I was a participant observer of the conflict and was therefore able to capture data, which adds to the relevance of this book for those that seek to better understand power-seeking insurgent groups and how to reduce conflict and the use of terrorism.

One cannot enter the diplomatic and academic discussion on the Middle East Conflict lightly. For credibility, it requires new insights that are unknown or have been overlooked by others. For this work, the contribution is empirical evidence of the dynamic relationship between Hamas’s use of violence, popular support measures, environmental conditions and Hamas’s own articulation of its values. The book describes a set of hypotheses, and tests those against empirical evidence gathered for this research in an attempt to further our collective understanding of the symbiotic relationship between Hamas and the Palestinian people and to persuade others, particularly policy leaders and academics, that empirical investigation and field-based scientific research comprise the best methods to understand the sustainability of power-seeking insurgent groups and the various ways to reduce or eliminate premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against non-combatants. In time, we will learn which evidence is most valuable in helping us reduce such violence. Until then, the empirical evidence is offered as a way to deepen our understanding and expand our toolbox for the types of policy approaches that can lessen or eliminate the use of politically motivated violence against non-combatants.

To put a fine point on it, this book offers a unique perspective on the nature of Hamas resistance by demonstrating under what conditions the group exercises violent resistance or refrains from doing so.

Illuminating the research

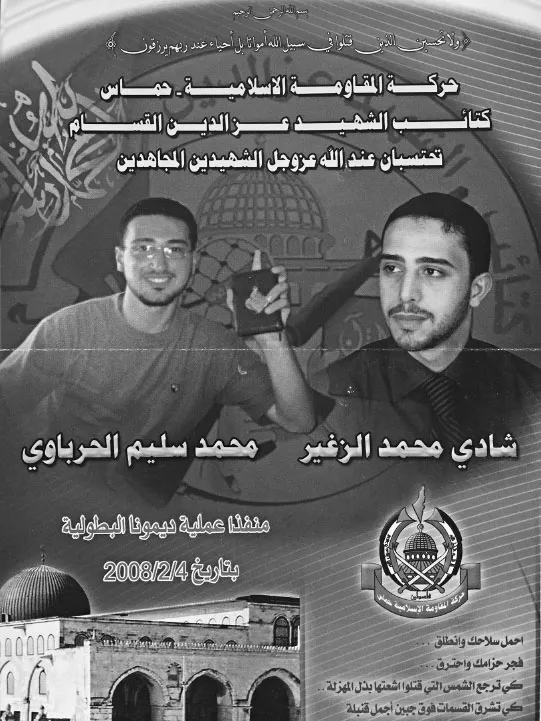

On the morning of 4 February 2008 Mohammed al-Herbawi and a fellow soccer teammate set off on a suicide-bombing mission departing from the West Bank to the Israeli city of Dimona, the home of Israel’s nuclear facility. By 10 am, Herbawi and friend made it to a shopping mall in Dimona, inside the Green Line,1 where one of them was able to detonate his vest killing 73-year-old Lyubov Razdolskaya and wounding 40 others. Both young men died in the operation. Herbawi, age 20, was from the University Neighborhood in Hebron, the largest city in the West Bank with a population of 165,000, located south of Jerusalem. The two teammates were following in the footsteps of ten others who in 2003 perpetrated either suicide bombings or armed attacks where death was nearly certain. All played for the Al-Jihad Mosque soccer team and all were loyal to Hamas.

Early in the morning on 6 February, two days later, I entered Hebron on my way to visit the Herbawi home and meet with his family. As we traversed the city toward the University Neighborhood, I noticed that the main thoroughfares were adorned with posters. Upon inquiry, my driver explained that they were Hamas posters honoring the actions of Herbawi and Zgyaer (his teammate and accomplice). As we arrived at our destination, the home of Mohammed Herbawi, several people had gathered outside the second-story apartment, presumably to show support for Herbawi’s actions and family. On each wall adjacent to the entrance of the home, posters similar to the others papering the city were prominently displayed. Once we exited the vehicle, we were quickly ushered up the stairs and into the family room of a modest three-bedroom home where Herbawi’s mother, younger brother, Ahmed, and a family friend greeted us. Despite the circumstances, we were offered tea and fruit and provided with other comforts in the usual Arab custom for invited guests. We spent nearly two hours talking with the family. During the conversation, the mother expressed anger and stated several times that had she known of her son’s intentions, she would have ‘stopped him from this destiny’. Each time she followed that statement with another, ‘he is a hero’. Herbawi’s family and friends were outwardly grief stricken, but all articulated great satisfaction that he had become a ‘martyr’ and that ‘Hamas was fighting the occupiers’. At the end of our visit, Ahmed offered me, with pride, a Hamas poster of his brother (see Figure 1.1).

I spent the rest of the day in the University Neighborhood with the Imam of the Al-Jihad Mosque and other families who lost their sons in the 2003 suicide bombings and attacks. During the day, it became evident that Hamas was endeared everywhere I went. This loyalty and support was clearly demonstrated by Fawzi al-Qawasmeh, the father of Hazem, a Hamas operative who was killed in a shooting attack on Kiryat Arba settlement in March 2003. Fawzi expressed anger over his son’s actions and declared that his son ‘ruined the family’s future’, claiming that he lost his mechanic’s bus garage in Jerusalem and that the Israelis destroyed their $200,000 home in response (an expensive home by Palestinian standards).2 He contrasted this anger with expressed pride in his son as a ‘hero’ and ‘martyr’. Though Fawzi and family experienced significant loss and hardship, he outwardly expressed support for Hamas as ‘fighting for the Palestinians against the occupiers’.

Contrast this grassroots support for Hamas with the following scene, which occurred 21 years prior. On 7 December 1987, a quadriplegic sheikh invited six guests to his home in Gaza with the intent of beginning a Palestinian resistance group that would espouse Islam as a central tenet of the resistance. Although the name was not selected for days, Hamas was effectively launched at the meeting with only seven members. Birthed from members of the Muslim Brotherhood of Gaza, Hamas was a fringe militant group that at best represented the ideas of only a small minority of the Palestinian population during a time in which the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) had convinced a large majority of Palestinians that a secular resistance movement, led by Fatah, was in the best interests of the people. Further, Hamas was in direct competition with another Islamic militant group started years earlier, the Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), for the Islamic resistance support of the Palestinian people. Yet, over the course of time, Hamas developed a growing support base that allowed it to win local elections in 2004, a national election in 2006 and endear a large segment of the population to its Islamic resistance ideology, including the unwavering support of a grief-stricken mother and father from Hebron who lost their children to Hamas militancy in the name of fighting the occupier. The dichotomy in the mother’s anger of her son’s final symbolic act and her unshakable support of Hamas is representative of many and is a testimony to the power and efficacy of Hamas’s 27-year engagement with the Palestinian people.

Figure 1.1 Hamas poster of Herbawi and Zgyaer (2008).

The contrasts in these two ethnographic illustrations demonstrate a remarkable change over the course of nearly three decades. Through engagement with the Palestinian population, Hamas was able to evolve from a small group to contend for and win national leadership even though a majority of the population is more moderate than the core supporters of the group.3 During this evolution, the group experienced the assassination of many of its leaders, was forced to operate the movement from underground, survived though traitors were in its midst, built an arsenal from a rifle to sophisticated mid-range rockets, used rocket propelled grenades, cyber-attacks and TV station spoofing, fought three external wars and one civil war, developed international relations for financial sustainability of the militant Ezzedeen al-Qassam Brigades (the official Hamas military wing) and learnt when its ability to project violent resistance was being threatened by violent acts of other Palestinian groups. It did all this while having to adapt its language, values and use of violent force to win and maintain support within the Palestinian population.

The multitude of causal factors influencing Hamas’s evolution are often overlooked by scholars and policy makers because distilling complexity into simplicity is often desired in these communities. Further, the complex and dynamic relationship between Hamas and the Palestinian people make it challenging for policy makers to predict the outcome of policy interventions. For example, after the takeover of Gaza by Hamas in 2007, the US, EU, Israel and the Palestinian Authority led by Mahmoud Abbas collaborated to shutter Hamas dawa (social welfare and religious training programs) operations in the West Bank. The intention behind the effort was to shut down militant operations emanating from the West Bank and to reduce the appeal and popular support for the group by removing its social service capacity. Yet, since late 2007, a majority of ground attacks (e.g. not rockets or mortars) against Israel were perpetrated by young Hamas militants from the West Bank.4 Further, Palestinian popular support for Hamas in the West Bank has not lessened since the shuttering of the dawa programs. It is important that we understand why support for Hamas has been so resilient in the West Bank despite international efforts to lessen it.5

What will become clear in this book is that Hamas’s identity is based on ‘violent resistance’. The Hamas Charter, published in 1988, details this and so do its current actions. What is missing is the understanding how it has maintained and strengthened its ability to violently resist over 25 years despite the efforts of many to crush it and the host of other influences that can cause organizations to wither and die. The complexity of Hamas’s actions over the years suggests that resistance requires malleability, stratagem and guile, not only toward enemies, but also in the relationship to its militant support base amongst the Palestinian people.

Introduction to the research

Hamas entered political life and politics before they strove for ballot boxes. Its purpose of transforming Palestinian life requires this interpretation and subjects it to the standard evaluation of political actors whose conduct can best be understood by their interactions with the people for whom it seeks to lead. Its stated purpose of establishing an Islamic resistance to Israeli occupation of lost land guarantees that violence or the lack thereof will be an important component of its political engagement with all Palestinians.

German philosopher Max Weber articulated in his work on Politics as Vocation (1918) that political groups remain suspended between the values of core supporters and responsibilities of provision for those that they govern. By applying this construct to the evaluation of Hamas’s behavior, it is possible to demonstrate the tension within the group to accommodate core supporters while also trying to broaden its political base of support with Palestinians that may not share the same views, particularly on the use of violence. The examination takes us through seemingly chaotic and fascinating events to expose the conditions, reasons and influences behind the armed group’s use of violence against Israelis.

The empirical examination begins with the group’s formation in 1987 (and refers to foundations much earlier) and ends in June 2015. Over time, Hamas has been suspended between its quest to achieve the values of its ardent supporters (reclamation of land through force) and the desire to grow popular support. This tension is reflected in how and when the group exercises violent resistance. This framework provides a simple construct to better understand the complex dynamics that result in Hamas’s use and non-use of violence under changing environmental conditions.

Research methods: the qualitative and quantitative approach

Field-based empirical investigation in conflict areas is critical to real understanding of the actual events, motivations and dynamics. In addition to using 25 years of data on violence and popular support measures, this book was structured to make the most of more than 70 field interviews conducted by the author ...