eBook - ePub

The Private Sector after Communism

New Entrepreneurial Firms in Transition Economies

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Private Sector after Communism

New Entrepreneurial Firms in Transition Economies

About this book

The transformation of state-owned enterprises into privately owned ones is commonly referred to as 'privatization'. Just as important as this process, though sometimes not given the attention it deserves and requires, is the establishment and expansion of new private firms.

This book analyzes new entrepreneurial firms that emerge and occasionally flourish after a period of state communism has come to an end. The authors rightly focus on the aftermath of the end of communism by looking first at the inevitable output decline, followed by an overview of new entrepreneurial firms. Specific East European examples are examined and the lessons which can be learned from these will interest academics and policy-makers alike.

Committed and knowledgeable authors in this book treat the sometimes emotive issue of transition-developing economies maturely and expertly. The result is a volume which will interest scholars with an interest in transition economics and politics, as well as those who actively work in transition economies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Old and new firms in decline and recovery

1 Transformational recession

Impact on the old state sector

Jan Winiecki

Introduction

The major fall of output in early transition from communist centrally planned to capitalist market economy became an issue very early in the transition process. The Polish economy, that began its transition program the earliest, that is on January 1, 1990, registered what at that time looked like a shockingly large output decline. Thus, industrial output fell by about 25 percent and GDP by 12 percent in 1990. It fell some more next year.

Critics of transition censured the fall as “the unbearable cost of transition.” Subsequently, it became a rallying cry of all those suspicious of or hostile to the market. “Big bang” (or “shock therapy” as the transition program was then called) was accused of generating a depression of unprecedented proportions — and an avoidable depression at that (see, e.g., Laski, 1990, and Bhaduri and Laski, 1992). Some analysts regarded the Polish and Czech big bang, that is a large package of measures, as the culprit and contrasted that with the allegedly different — and more successful — gradual transition in Hungary (see, e.g., Dervis and Condon, 1994). However, already in the same year of 1992 it transpired that there was little difference in the aggregate output numbers between Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia.

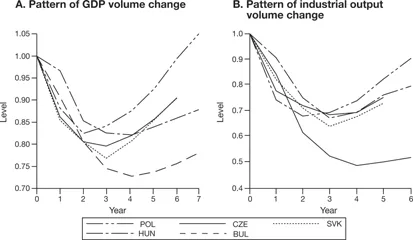

A year later, in 1993, one of the keenest observers of the scene at the time, Kornai (1993), noted that that output declined everywhere : in big bang countries and in “gradualist” countries, in internationally indebted countries and in debt-free countries like the former Czechoslovakia, in countries consistently following the transition program and in those that did not. Figure 1.1A and 1.1B (from Blanchard, 1997), reflects this observation very well as it shows the almost identical pattern of output fall, measured in years from the beginning of the transition program (not in calendar years). It is worth noting that the very large output fall also affected countries that did not follow any transition program (such as, e.g., Ukraine).

Industrial statistics of post-communist countries reveal that in the early transition, or “transformational recession” (Kornai's expression reflecting

Figure 1.1 Pattern of GDP and industrial output in East-Central Europe volume change in transition.

Note: Value in the year before transition =1.0.

Source: Blanchard, 1997.

Source: Blanchard, 1997.

the process of removing various structural distortions), or elimination of “pure socialist production” not needed under normal circumstances (L. Balcerowicz, 1995), output declines were very large everywhere. The data for the first three to four years of transition, concerning industrial output, confirm the pattern from Figure 1.1 for a larger number of East-Central European and East European countries (see Table 1.1).

Consequently, the accusations about the “cruelty” of shock therapy subsided somewhat and a near-consensus view emerged that output fall at the start of transition was all but unavoidable (for a good summary, see Csaba, 1998). Kornai's definition of “transformational recession” has been widely accepted. Of course, not everybody agreed. Every now and then one hears voices of unrepentant accusers. Those who dislike transition, more precisely the direction of change, have an obvious interest in repeating the baseless accusations ad nauseam. After all, the propaganda rules apply here as well. If you repeat the untruth often enough it may continue to compete with truth for the attention of some readers. Curiously, however, although analysts largely agreed on basic facts, they nonetheless “agreed to disagree” on their causes. A range of views has been formulated as to the causes of such a very large output fall — and these views differed sharply.

Table 1.1 Aggregate industrial output fall in selected post-communist countries of East-Central and Eastern Europe (calculated from the start of transition)

| Country | Years | Output change % |

| Bulgaria | 1991–93 | 41.3 |

| Czech Republic | 1991–93 | −31.3 |

| Hungary | 1990–92 | −30.7 |

| Poland | 1990–92 | −28.3 |

| Romania | 1991–94 | −36.9 |

| Lithuania | 1992–94 | −60.2 |

| Belarus | 1992–95 | −32.0 |

| Russia | 1992–95 | −46.1 |

| Ukraine | 1992–95 | −44.7 |

Sources: Countries in Transition, 1999, by the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Vienna; Transition Report, 1996, by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, London; Statistical Yearbook, 1998, Central Statistical Office of Poland, Warsaw.

Note: No data are available for industrial production in early 1990s for Estonia, Latvia, and Moldova. Post-communist Yugoslav countries, as well as Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan have not been included due to the additional impact of civil war on the pattern and level of output.

However, with transition moving, at least in “success stories,” from the phase of transformational recession to recovery, the theoretical debate shifted from causes of output fall to causes of output recovery (or the lack of it), and theoretical considerations about the former subsided as well. The latter story is analyzed in detail in Chapter 2. Therefore, I would like to continue here with the early phase of output fall. The debate on its causes, stressed above, subsided on a note of complete disagreement. Whenever the issue has been broached in later considerations, the views from early transition were simply presented again, without much added reflection on the subject (compare, e.g., Gomulka, 1991 and 1998).

However, such “agreement on disagreement” is intellectually highly unsatisfactory. After all, this has been a — if not the — major theoretical puzzle of early transition (see, e.g., Winiecki, 2000a). Stabilization cum liberalization outside the post-communist world usually entailed a relatively limited output loss, or, under certain circumstances, even slight output increase. Leaving unsolved the puzzle of a very large output fall in the case of post-communist economies undergoing similar process suggests a major weakness in theorizing on the economics of transition.

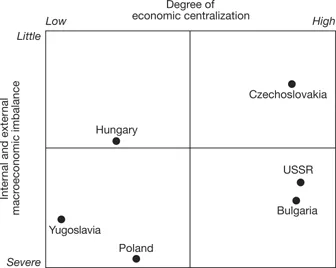

Moreover, not only shock therapy (or “big bang”) offered little support for the view stressing its role as the major determinant of output fall, but also initial conditions as debated at the time (see, e.g., Fischer and Gelb, 1991) did not do any better in this respect. Post-communist countries differed among

Figure 1.2 Initial conditions in post-communist economies.

Source: S. Fischerand A. Gelb, 1991: 91–105.

themselves with respect to the degree of economic centralization and initial macroeconomic imbalance, as shown in Figure 1.2 (adapted from Fischer and Gelb), but again this differentiation did not offer us any clue as to the cause (or causes) of a very large output fall everywhere, regardless of initial conditions.

The author suggests, therefore, the following. If neither transition programs as such nor initial conditions before the start of transition seem to have influenced the drastic fall of output decisively, then the cause(s) of a very large fall of output must be rooted elsewhere. That is, in the workings (or the mechanics) of the communist economic system. Such is, by the way, the position taken consistently by this author in his earlier writings and elaborated over time (Winiecki, 1990,1991b, 1993, 1995).

Therefore, my proposal is to look first, in an orderly manner, at the structure of incentives in a communist centrally planned economy (whether reformed or not). This should help us to discover what types of output would be prime candidates for disappearance, or at least marked shrinkage, in the context of systemic change.

Next, the author will look for some quantitative differences in output patterns between communist planned and capitalist market economies, and then at the discernible shifts from the former to the latter, during the transition process. Having established the credentials of the determinants offered in explanation of drastic output fall, I would like to compare, in the subsequent sections, how well the theoretical explanation offered fares vis-à-vis other contending explanations, both in terms of internal consistency and available evidence. The chapter ends with a summary.

Structure of incentives in the communist economies and resultant distortionary output patterns

The basic hypothesis of this author has long been (see, e.g., Winiecki, 1986 and 1988) that certain system-specific characteristics induced state enterprises to report a very peculiar type of output. It was output that could only be created — in real life or in statistical reports — in the communist centrally planned economy, and nowhere else.

The fundamental consequence thereof within the framework of transition has been the existence of output that would, in consequence, disappear in an economic system that does not generate communist system-specific distortions. Since the disappearance of such output would be associated with the change in the structure of incentives, both formal and informal, I suggest to start with an analysis of the incentives in the communist economic system that generated such output in the first place.

As these incentives generated a wide range of distortionary output patterns, let me present the more important ones, beginning with what I dubbed years ago as “measurement without markets” (Winiecki, 1991: 32). There is a high cost of measuring economic performance in the case of complex goods and activities. The necessary reliance on measurement by proxy may give rise to moral hazard, as stressed by the property rights' school. Where performance is too costly to be measured in its entirety, measurement is limited to a few variables only. Economic agents are then tempted to concentrate on these few variables and neglect the performance along with other variables (see, North, 1990). This moral hazard was strongly amplified in communist economies by the lack of markets and inefficient property rights structure (on the comparative analysis of the latter, see Pejovich, 1990, and Winiecki, 1992). In a nutshell, when managers and workers are paid by what they tell (i.e. report to higher authorities) rather than by what they sell, incentives are created to doctor the reports to one's pecuniary advantage. The whole range of manipulative techniques emerged in due time in the communist economies.

The first, and the simplest, way of doctoring reports was limited to reporting higher output than was actually the case. Given the measurement costs without markets that verify, through sales transactions, the validity of the claims, such claims stood a reasonable chance of not being discovered by those on the higher rungs of the economic bureaucracy. Russians gave such doctoring the appropriate name pripiski (write-ins).

The second set of manipulative techniques concerned hidden changes in output structure. Thus, first, enterprises made changes in the output mix, by increasing the weight of higher-priced substitutes. Increased aggregate output value enabled managers and workers to fulfill or exceed plan target more easily. Secon...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Introduction

- PART I Old and new firms in decline and recovery

- PART II The new private sector

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Private Sector after Communism by Vladimir Banacek,Mihaly Laki,Jan Winiecki in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.