![]()

1 Overview

“The inflation tax is an issue of the first importance.”

(R. E. Lucas, Jr., 1996, Nobel Lecture, p. 675)

Bob Lucas describes in his Nobel Address (Lucas 1996) the temporary positive relation between inflation and employment that can exist in a Phillips curve relation, as in his Nobel cited paper that modeled a Phillips curve in general equilibrium (Lucas 1972). But Lucas also emphasizes in his Nobel address the permanent long run effects of inflation, and in particular the distortions caused by the inflation tax. This collection focuses on the inflation tax distortions.

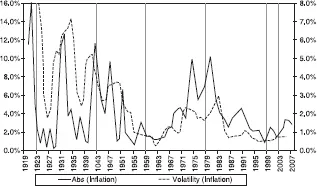

Inflation has fluctuated greatly over the last century. For the US, Figure 1.1 shows the large swings during the Depression, WWII, and the 1970s and 1980s “Great Inflation”. Here the absolute value of the inflation rate (left axis) and its volatility (right axis) are given from 1919 to 2007, and they are seen to move together. Despite the advent of inflation targeting, recent inflation has surged again; inflation has risen more than four-fold from an annual rate of 1.1% in June 2002 to 5.0% in June 2008.1

Figure 1.1 Absolute value of US inflation and its volatility, 1919–2007.

Recurrent inflation means that the distortions of the inflation tax unremittingly continue to affect the economy. This book brings together chapters that build a progression in inflation tax theory, with the aim of enabling better analysis of the many distortions that inflation causes. The chapters start with a simple way to add credit into a general equilibrium stationary model, so that any good can be bought with cash or credit. They end with a fully micro-founded bank production technology that produces the credit as in the financial intermediation approach to banking. On the way, the chapters develop extensions which transform a primitive approach towards including credit into a more advanced approach, while building the neoclassical monetary model. And they go from an initial deterministic economy with no growth to a setting of stochastic shocks with endogenous growth, a new frontier.

A theme running through the papers is that monetary economics in general equilibrium is helped by having a good money demand function underlying the theory.2 A proper endogenous money demand sets up arguably the best foundation from which to make extensions of monetary economics from the basic model. At the same time that money demand is better modelled, this also “endogenizes” the velocity of money in a viable way.

Endogenizing velocity has been a challenge in the literature. For example, Lucas lets velocity be exogenous in Lucas (1988a) and Alvarez, Lucas, and Weber (2001), while setting it at one in his original cash-in-advance economy. Lucas and Stokey (1983) endogenize velocity using a credit good in the utility function. This makes velocity a function of utility parameters, and leaves no role for the cost of credit versus the cost of cash. And Hodrick, Kocherlakota, and Lucas (1991) find this cash-credit good model was not able to fit the velocity data well. Lucas (2000) also endogenizes velocity using the most standard models of money-in-the-utility function and shopping time, although again the velocity depends closely on utility parameters and hard-to-interpret transaction cost specifications. Typically these parameters are set so as to yield a constant interest elasticity of money demand, as in the partial equilibrium Baumol (1952) money demand model.

In contrast, this collection solves the velocity problem by the way in which the cost of exchange credit enters the economy. This gives a natural, direct, and microfounded way to solve the problem. At the same time, it opens up a way to extend the standard monetary economy in the direction of greater realism. By bringing in banking to produce the credit, the financial sector becomes the direct determinate of the shape of the money demand function, because the credit is a perfect substitute for the fiat money in exchange.

With velocity built upon solid banking foundations, calibrating money demand is no longer a task of assigning utility parameters, or general transactions function parameters in order to get some constant interest elasticity. Nor is money demand an exogonous function assumed at the end of a model in order to residually determine money supply from an ad hoc Taylor rule. Rather it is an integral part of the model that largely determines the nature of the monetary results. And money demand ends up being well-defined across the whole range of inflation rates, including at the Friedman (1969) optimum. The result is arguably a greater realism of money demand functions per se, and a further development of the inflation tax analysis, as Lucas (1996) encourages in his Nobel lecture.

The book’s collection gives a new perspective on some classic issues and leads to new results which range from welfare theory, including the welfare cost of inflation, and first and second-best money and credit optimums (Part I), to money demand and velocity investigations (Part II), to growth (Part III), and business cycle theory (Part IV).

Part I (Chapters 2–6) shows how to develop the basic cash-in-advance model so as to include exchange credit, endogenize velocity in a rudimentary way, and to show how this compares to traditional partial equilibrium theories, in terms of the cost of inflation. The optimality of money and credit is then examined within such models, as well as within a model that uses the more advanced single-consumption approach to including credit that forms the basis for the money demand, growth and business cycle applications.

Indeed, starting from the Chapter 2 article, a type of standard microfoundation is built in the collection here. This microfoundation is based in the traditional sense that an industry produces a product with profit maximization and an industry production function that is consistence with industry-level empirical evidence. While taking only small steps in Chapter 2, by Chapter 19 a fully microfounded banking production function is used to supply the credit. And note that all of the eleven chapters with a single good approach with credit, these being Chapters 6–9, 11–15, and 17–18, have the same type of credit production function as in Chapter 19, even though in these other chapters the explicit link to the banking microfoundations is not made, as it is in Chapter 19.

The result is to endogenize velocity so that any degree of money is used depending on the relative cost of money versus credit, and so that the use of the cash constraint cannot easily be viewed as being exogenously imposed. In fact, over the course of the chapters, it emerges that the cash constraint embodies the credit production technology, and is in fact the “exchange technology”, rather than the “cash constraint” per se.

Part II (Chapters 7–10) develops and tests the money demand and velocity functions; empirical estimations are done for both developed and transition countries studies. Parts III and IV show useful applications of this theory: as a means of seeing how inflation as a tax can lower growth, be inter-related with financial development, and can explain monetary business cycles. The collection goes to the ever-shifting frontier in its topics of welfare cost, money demand, velocity, inflation effects on endogenous growth, and monetary business cycles.

1.1 Inflation and welfare

Lucas (1980) suggested in a footnote that velocity could be endogenized by having a credit technology for buying goods with credit alongside the ability to buy goods with money (cash). Prescott (1987) developed such a technology with both cash and credit use across a store continuum. He specified exogenously a marginal store that divided the continuum between stores using cash and those using credit. On the chalk board, Bob Lucas demonstrated how to endogenize the choice of this Prescott marginal store in a static model, whereby the choice to use cash versus credit at a particular store depended upon the time cost of using credit at each store (motivated by Karni, 1974), as compared to the foregone interest cost of using money.

Making the choice of the marginal store endogenous within a dynamic Lucas (1980) type model led to the first article in this collection, Chapter 2 “The Welfare Costs of Inflation in a Cash-in-Advance Model with Costly Credit”. Here an extra first-order condition is added to the standard cash-only Lucas (1980) economy, this being the choice of the marginal store of the Prescott continuum. During the revisions of the Chapter 2 article, Bob King helpfully pointed out that this additional condition made the model a generalization of Baumol’s (1952) original transactions cost model, in which the costs of alternative means of exchange (carrying cash or using banking) are minimized optimally.

Baumol’s (1952) model implies the well-known square root money demand function, with a constant interest elasticity of money demand equal to –0.5, the number for example that Lucas (2000) uses to specify his shopping time model. However, the money demand function results by rearranging the firstorder condition that sets the marginal cost of money equal to the marginal cost of banking. Chapter 2 focuses on this aspect: the equating the marginal cost of different means of exchange. The chapter derives the interest elasticity of money demand to emphasize that the credit option makes the money demand much more interest elastic. Consequently, as follows from Ramsey (1927) logic, when taxing a much more elastic good (money), the welfare cost of the inflation tax is higher than in models omitting such a Prescott exchange credit channel. And by including this exchange credit, which requires the use of time within a technology of credit production, the velocity of money is endogenized in a way suggested by Lucas (1980).

The Chapter 2 article lays the foundation of the remaining papers in the collection. It provides a feasible way to model exchange credit, but in an abstract way, in that its credit production technology is an arbitrary linear one at each store. Although this still gives a type of upward sloping marginal cost function for credit use the store continuum set-up does not make it easy to integrate credit use within the mainstream neoclassical growth and business cycle theory; in contrast Lucas’s (1980) economy starts with a similar continuum of goods but he creates a composite aggregate consumption basket that allows for easy integration of the cash-in-advance approach within the neoclassical model. However, this endogenous store continuum approach with credit is useful and does continue to be used, as in Ireland (1994b), Marquis and Reffett (1994), Erosa and Ventura (2002), and Khan, King, and Wolman (2003).

One immediate consequence of the Chapter 2 velocity solution is that it addresses a criticism of the basic Lucas (1980) model, this being that the cash constraint is exogenously imposed. This criticism is rather unfair, and inaccurate, in that Lucas (1980) goes to some length to prove that the original cash-only constraint is endogenously found to be binding, and not assumed exogenously. Yet this criticism is still invoked, especially in “deep foundation” literature that claims to provide a non-standard “microfoundations” for the existence of Lucas’s cash-in-advance constraint, as based in search within decentralized markets; see also Townsend (1978). Meeting this criticism head-on, Chapter 2 marks a way forward with velocity endogenous, with cash and credit being perfect substitutes, with costs determining the consumer choice of the mix of exchange means, and with near zero or 100% cash use being possible outcomes of the consumer choice based on relative cost.

Chapter 3, “A Comparison of Partial and General Equilibrium Estimates of the Welfare Cost of Inflation”, looks more in depth at what is behind the welfare cost estimate of the Chapter 2 model, and compares this measure to measures based on the traditional partial equilibrium money demand literature. It asks whether partial equilibrium estimates are consistent with, or somehow superseded by, the newer general equilibrium measures such as that put forth in Lucas’s (1993a) Chicago working paper (published later as Lucas 2000). The main puzzle tackled in Chapter 3 is that partial equilibrium based estimates tend to be below general equilibrium based estimates. To resolve this, the paper sets out how partial equilibrium estimates are simply the area of the lost consumer surplus under the money demand function due to an inflation tax, as first described by Martin Bailey (1956). In contrast the general equilibrium estimates are equal to the real income necessary to compensate the representative agent for having to face some positive inflation tax instead of a zero tax at the first-best optimum. Are these estimates one and the same? The paper shows that within the Chapter 2 economy the general equilibrium compensating income is almost exactly equal to the lost consumer surplus under the money demand function of the same Chapter 2 economy. And further, the implication is that the composition of the lost surplus depends on what is built into the economy.

In the Chapter 2 economy, the welfare cost estimate includes both the resource cost of producing the exchange credit, in order to avoid the inflation tax; plus it includes the distortion of the ensuing goods to leisure substitution that is caused by the inflation tax. By comparison, Lucas (2000) excludes the leisure channel and focuses on just the resource cost that results from avoiding the use of money (within a shopping time economy). So the welfare cost of inflation, which is the area under the money demand within the general equilibrium model, may represent just the resource cost of avoidance or also other distortions; if these are built into the economy. Lucas (2000) makes a similar point to that of Chapter 3 in that Lucas shows how to compute the general equilibrium estimate directly as a function of the model’s own money demand. The implication is that the money demand function of partial equilibrium approaches fully underlies the general equilibrium estimate of the compensating income, as long as the money demand used in the comparison is exactly that function that is derived from the general equilibrium economy, rather than some separately estimated money demand function.

The Chapter 3 paper is also interesting because the literature has suggested different answers to the question of how partial and general equilibrium estimates compare. For example, Dotsey and Ireland (1996) calibrate an estimate of the welfare cost of inflation from a general equilibrium shopping time economy and compare this to an econometrically estimated partial equilibriu...