![]()

1 Introduction

The poor craftsman and the wealthy inventor

1.1 Opening story

Our history books are filled with success stories about great innovations, such as agriculture, writing, seafaring, metal working, the printing press, the steam engine, electricity, the combustion engine, computers and genetic engineering, to name a few. All of these, and many other less- well-known or forgotten ones, may have shaped the history of humanity in ways that go well beyond even what the history book will admit. I would like to recount one of the fabulous tales (largely following the account in He, 1994), the tale of a financially troubled craftsman in the late European middle ages. His name was Johann Gutenberg, the story of his early life remains largely unknown. Historical records of lawsuits, however, establish that he had been working on the printing press with movable letters since at least 1439. It took him another 15 years – always on the edge of bankruptcy and often sued by various people for debts he was unable to repay – to make his invention workable and economically efficient. In the subsequent two decades, the use of this technology spread throughout the continent, the numbers of volumes printed in European countries have risen exponentially ever since (Baten and van Zanden, 2008). It has been suggested that this technology was the true foundation of modern Europe, that it facilitated both the consolidation of European nation states and the modernization of the economic organization during the early modern era (Anderson, 1991 [1983]). Concurring popular theories hold that modern capitalism was driven by either the protestant ethic that came into being because of the religious reformation in Europe, or by the vast amounts of gold and silver acquired by Europeans in America after Columbus’ (re-)discovery of that continent in 1492. The religious reformation relied crucially on the works of reformation leaders being printed and distributed among the literate upper class of the time. Furthermore, Columbus was reportedly inspired to undertake his voyage by reading a printed copy of Marco Polo’s travel report. It is beyond doubt that the invention and subsequent widespread use of printing with movable letters in Europe sparked profound social, economic and technological changes, and a variety of further innovations.

Roughly 400 years earlier and 5000 miles away, another commoner (though probably a wealthy man), Bi Shen in Sung dynasty China, had the very same idea. Technical details of his set of movable letters for printing are well-documented and were well enough known in China to inspire other inventors to work on improving that technology during the following centuries. The technology, however, failed to be adopted more widely for economic purposes in spite of a reportedly flourishing printing business in China at the time (He, 1994). During the life of Bi Shen, China was a well-organized empire with a complex economy, standardized system of administration and academics, and advanced technology, while Europe was little more than a collection of what today would be called failed states, arranged around the persisting religious authority (the papacy) of a fallen empire (the Western Roman Empire). Yet following the invention of the printing press with movable letters – and at least partly as a consequence of it – Europe proved to be much more successful politically, economically and technologically in almost every respect.

What is usually given as an explanation for this phenomenon – the utter failure of a promising innovation in an economically more developed region and its great success in a less developed one – is of course nothing less than the essence of these regions’ cultures, religious beliefs and economic organization (in neo-Schumpeterian terms, the innovation system) (He, 1994). These all-encompassing, deterministic explanations may, however, not exactly match up to the historic reality. As He (1994) details, the printing business without movable letters (i.e. block printing) was quite successful in China at the time, much more successful than in Europe at the time of Johann Gutenberg’s innovation. It is also conceivable that printing with movable letters would have led to social and economic processes not unlike those sparked by the advent of the printing press in Europe. He offers yet another explanation: Bi Shen’s invention may have faced fierce competition from a developed industry with a well-established standard (block printing) such that no one would have wanted to invest in movable letter printing due to uncertain economic prospects for this technology, while block printing was not widespread in Europe in Johann Gutenberg’s times. (Furthermore, the very small number of different characters required for the Latin alphabet compared to Chinese script may have played a part.) In this way, it might well have been the mere fortunes of history that shaped the future of Europe, China and the world rather than religion, institutional setting or the cultural attitudes of these societies. David and other scholars (David, 1985, 1992; David and Bunn, 1988; David and Steinmueller, 1994) discuss a number of similar cases including the QWERTY keyboard, direct current and alternating current electricity, and hardware standards and operating systems in modern computer technology. There are many more examples, from the technologies often reviewed in history books, to the many standards that have evolved in a very short time during the rise of information and communication technology that will more closely be examined in Chapter 6.

1.2 Shedding light on the trajectories of technological change and economic growth

1439 is the year in which historical records confirm that Johann Gutenberg had started to work on his innovation – the printing press with movable letters – that would shape the future of the world and put the future of Europe on a trajectory of development very different from that of China and every other region of the world. Exactly 500 years later – in 1939 – the first influential theories of economic growth were published (Harrod, 1939; Samuelson, 1939a,b), theories that would eventually help to put economic growth theory on a trajectory of development ignorant of the effects of path dependence – even though the models of 1939 themselves were in no way equilibrium models like the successor theories developed by Solow (1956, 1957) or the proponents of the endogenous growth theory (Uzawa, 1965; Cass, 1966; Lucas, 1988), and even though the models of 1939 would likewise nourish the tradition of Kaldorian growth models that explicitly embraced increasing returns and thus different possible paths of development (Kaldor, 1940, 1972; León-Ledesma, 2000).

The data patterns to be explained in economic growth are basically the following three:

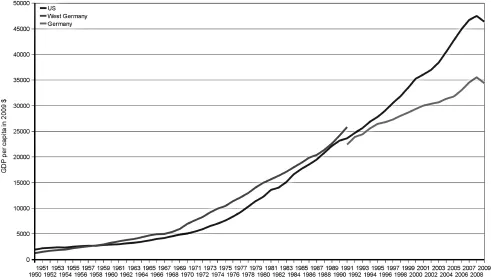

• On average superlinear growth (see the development of the GDP of Germany and the USA over the past decades in Figure 1.1 as an example).

• Occasional and sudden decline as aresult of crises (as in 2009 in Figure 1.1). That may, however, be explained by financial sector instabilities and occasionally wars and political decisions, although some theories of economic cycles try to internalize this, e.g. Minsky (1980) and Keen (1995). This phenomenon will not be a central focus of the current study.

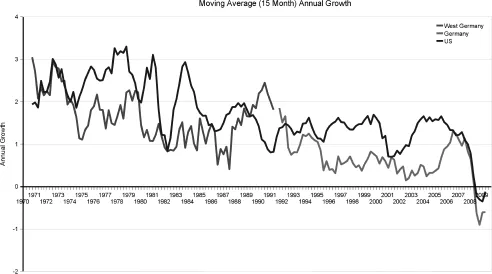

• Persisting and possibly regular fluctuations in the growth rate (as seen in Figure 1.2), though the regularity is doubtful. These fluctuations lead to a pattern of alternating slow and rapid growth (which is not obvious from Figure 1.1 due to the scale of that figure).

| Figure 1.1 | GDP per capita in Germany and the USA. (Data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (2010) and the German Federal Statistical Office (2010)) |

| Figure 1.2 | Annual GDP per capita growth rates of Germany and the USA (three-month data), with a 15-month moving average filter. (Data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (2010) and the German Federal Statistical Office (2010)) |

Many efforts have been made to approach both economic growth and so-called ‘growth cycles’,1 proposing a number of different mathematical mechanisms for both and offering different economic interpretations of their respective mechanism. The models currently favoured by the economic mainstream are mechanisms of endogenous growth; exponential growth with an optimal growth rate that is optimal in the sense of (approximately) maximizing utility in an infinite horizon optimization problem (Uzawa, 1965; Cass, 1966; Lucas, 1988). Random shocks are believed to cause a coordinated response by rational agents, thus forming constant cycle patterns (Lucas, 1972, 1975, 1981). This theory, the neoclassical approach, has however been heavily criticized (Albin, 1987; Mirowski, 1989; Albin and Foley, 1992; Foley, 1998, 2010; Keen, 2001; Chen, 2002; Wheat, 2009) and a number of other research traditions have offered alternative models, including evolutionary economists (mostly Schumpeterians, for instance Nelson and Winter (1974, 1982a) or Silverberg and Lehnert (1993, 1994)), Marxian radicals (e.g. Keen (1995)), and Kaldorians (Lorenz, 1987; León-Ledesma, 2000).

Among the few things that are more or less uncontested is the assessment that economic growth results mostly from technological improvements (including knowledge about technologies and thus human capital) rather than strict capital growth as has been modelled in early growth models. For evolutionary (and other Schumpeterian) approaches (Nelson and Winter, 1974, 1982a; Conlisk, 1989; Silverberg and Lehnert, 1993, 1994), technological innovation and diffusion2 plays the crucial part in economic growth, Solow – whose model treated the technology level as an exogenous factor – admits in his empirical application of his model (Solow, 1957) that a substantial part of actual growth must be due to technological improvement, and the models of endogenous growth (Uzawa, 1965; Cass, 1966; Romer, 1986; Lucas, 1988) usually optimize over investments in ‘human capital’ that might just as easily be interpreted as an influence that works primarily through either innovation or the efficient application of technology. Economic cycles on the other hand remain a contested subject. Evolutionary theories generate ‘circular’ patterns (repeated alterations in the growth rate) through the pattern of innovation and the subsequent diffusion of innovative technology, while other explanations mostly seem to be dynamic systems that lead to clockwork-like precision in the model’s cycles which may seem odd compared to the reality of ‘cycles’.

None of these models, however, has tried to examine the patterns of technological change that obviously play such a crucial part in economic growth in more detail. As the above story of Johann Gutenberg and Bi Shen shows, the success of a technology may depend not only on the technology itself but rather also on specific – seemingly random – details of the environmental conditions. In particular, the presence or absence of similar established technologies has an impact on the chances of an innovative technology eventually establishing itself as an industry standard which in turn governs the adoption decisions of potential users. Mathematically, this relation, known as a network effect – and, as the network of a technology does also influence the chances of other competing technologies, a network externality (Katz and Shapiro, 1985) – is rather simple. It merely states that the probability of a technology being adopted by an agent increases with the number of previous adopters and the relative number of adopters compared to alternative technologies. This process is obviously path dependent: for several available technologies a process of (sequential) adoption decisions converges to the universal adoption of one of those technologies (David, 1985; Arthur, 1989). A two-dimensional variant of that system (with shares x and probabilities p(x)) is shown in Figure 1.3. Such a technology will, even with constant progress in technological research, be able to defend its position as the industry standard for a long time, a phenomenon known as technological lock-in (Arthur et al., 1987; Arthur, 1989). Given the probably widespread occurrence of such lock-ins, an industry will only in rare historical events break...