1 Introduction

I think that there’s power in that we’re able to bring such a diverse group together. It’s hard; it’s really hard.

A program officer at an interorganizational immigrant network

INTERORGANIZATIONAL GOAL-DIRECTED NETWORKS: POPULAR AND DIFFICULT TO MANAGE

Popular, but Difficult to Manage

Imagine the following scene: Several nonprofit organizations get together and decide to collaborate, to jointly influence the city’s education policies. All nonprofits agree that immigrant rights are not being sufficiently pro- tected under the current policies: At some schools, newly arrived children do not get sufficient support; at other schools, second language courses, in addition to English, are few and poorly taught; those areas of the city densely populated with first- and second-generation immigrants have fewer (and less qualified) schools; and undocumented children often bump into administrative barriers when applying for schooling aids due to their legal status. During their second meeting, the nonprofits’ directors discuss how they are going to act together and begin developing a joint advocacy strategy. The director of a nonprofit serving mostly first- and second-gen- eration Chinese Americans proposes to set up a series of meetings with the city’s Mayor and its Councilor of Education. The representative of another nonprofit sees this strategy as legitimizing the unfairness—her nonprofit serves mostly undocumented Latino immigrants—and proposes a march to put pressure on the Mayor. The advocacy director of yet another non- profit, whose constituents are mostly Mexicans, argues that it is essential to demand for bilingual education, while the leader of a union replies that this demand would be counterproductive and that it is currently not a pri- ority. The discrepancies among the different nonprofits cool off the initial stamina and the collaborative eventually stagnates.

The above fictional situation is a gross simplification but should illus- trate how difficult it is to get different organizations to work together. In fact, it is well known that managing goal-directed networks is an inherently difficult task and by no means an easy option (Human & Provan, 2000). Business alliance scholars estimate that more than 50 percent of alliances fail (Kelly, Schaan, & Jonacas, 2002; Park & Ungson, 2001). Success rates are not available for public or nonprofit networks, but Huxham and Van- gen (2000c) have identified how alliances often succumb to what they term collaborative inertia. Networks generally are difficult to manage because they are complex (Park & Ungson, 2001) and because collaborations are dynamic and ambiguous (Huxham & Vangen, 2000a). This book argues that goal-directed networks are difficult to manage because they imply an inherent tension between diversity and unity among network members.

In the context of organizational networks, unity means all network members being in agreement, without deviation. Diversity means variabil- ity in structural and institutional traits across network members, not only with respect to differing organizational demographics and cultures but also to comparable factors within fields and populations of organizations (e.g. budget, size, goals). Network governance implies dealing with unity and diversity simultaneously, generating a paradoxical tension: In fragmented settings like networks, the potential for collaborative advantage depends on the ability of each partner to bring different resources to the group. This much-needed diversity, however, is a function of organizational difference, which reveals conflicts in the collaboration (Bingham & O’Leary, 2008; Huxham & Beech, 2003). This tension is the central thread of this book.

The existing knowledge on networks, in general, implicitly points toward tension (the duality of coexisting contradictory goals and/or processes) and suggests that the management of tensions has an impact on the network’s success. More explicitly, previous research has identified what may well be the central tension in networks: The paradoxical tension between unity and diversity (Ospina & Saz-Carranza, 2010). Attention to this tension is sur- prisingly rare when compared to the by-now-common integration/differen- tiation tension found in single organizations (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967).

This tension offers great potential to help managers understand the nature of networks—and scholars to develop theory and generate knowl- edge in the organizational studies field. This book provides practitioners with some useful concepts that do not obviate the complexity, serving instead as guiding frameworks.

The Management of Goal-Directed Networks

Interorganizational goal-directed networks are increasingly popular orga- nizing mechanisms used to confront complex problems, especially in the public and nonprofit sectors. Yet managing these networks is a difficult task. This book shows how successful networks are managed.

Specifically, this book focuses on goal-directed networks of organiza- tions as opposed to social (or serendipitous) networks comprised of individ- uals who happen to connect. An interorganizational network is a long-term cooperative relationship among organizations in which each entity retains control over its own resources but jointly decides with others on their col- lective use (Brass, Galaskiewicz, Greve, & Tsai, 2004). These cooperative arrangements are also referred to as partnerships, strategic alliances, inter- organizational relationships, coalitions, cooperative arrangements, or col- laborative agreements (Provan, Fish, & Sydow, 2007).

This book focuses specifically on goal-directed networks. These repre- sent “groups of three or more legally autonomous organizations that work together to achieve not only their own goals but also a collective goal” (Pro- van & Kenis, 2008; 231)—hence goal-directed. For example, West Network, studied in this book, was created by different progressive nonprofits to coor- dinate collective advocacy actions to defeat anti-immigrant ballot measures that were being prepared for circulation to voters in a west coast state.

Networks, Networks, Networks

It is particularly important to distinguish goal-directed networks from ser- endipitous types of interorganizational networks (Kilduff & Tsai, 2003). However, first of all, we need to take one step back and define specifically what we mean by network , a term that is possibly overused in all aspects of academic discourse as well as daily life. Network refers to both an analytic perspective and an organizing logic (Knight, 2005; Powell & Smith-Doerr,

1994; Wellman, 1988). This book uses the term in its latter meaning.

As an analytic perspective, network emphasizes the relational aspects of actors, and the term is used as a metaphor for conceptualizing and under- standing social reality (Dowding, 1995). This use is exemplified by—but not limited to—the social network analysis methodology and supports the idea that actors may be best conceptualized as embedded in a network of social relations (Granovetter, 1992). This use of the term has been applied to all kinds of groupings of actors, including individuals and organizations. When the term is used in this sense, we often refer to “social networks.”

In social networks, the formal and informal links between all organiza- tions constitute a network. Within a social network, no single person or orga- nization, with the exception of the analyst, needs to be consciously aware of the network as a whole. These are analytical constructs. Under this approach, we find ego-networks, that is, the networks that arise from a single organi- zation’s diverse interrelationships with external organizations (for example, through its contracts), informal friendships among employees, and the orga- nization’s communications efforts.1 A specific type of social network—the policy and program implementation network—exists within the public sec- tor, and is made up of the contractual links between public agencies and pri- vate providers under a concrete public policy, such as the provision of mental health services. Another type of social network is the policy network. In this case, a network is constituted by the different, interdependent organizations within the same policy field they are trying to influence and are, in turn, influ- enced by public policies. Actors in policy network nodes do not need to be aware of one another, and they are seldom completely formalized, and most often are more analytical than real or consciously interacting entities.

As an organizing logic, networks have been contrasted with traditional market and hierarchy forms (Powell, 1990). The latter are the two main con- flicting interorganizational coordination modes (Williamson, 1975)—the means to arrange the relationships between different organizations (Lowndes & Skelcher, 1998). The market coordinates relationships automatically; the hierarchy does so through authority; the network by cooperation.

The three coordination modes—markets, hierarchies, and networks— may be roughly characterized by coordination through competition, direct coordination, and coordination through cooperation (Hewitt, 2000), or as markets, bureaucracies, and clans (Ouchi, 1980). In this book, network refers to a concrete interorganizational coordination mode.

Relationships between Organizations: Markets, Hierarchies, or Networks

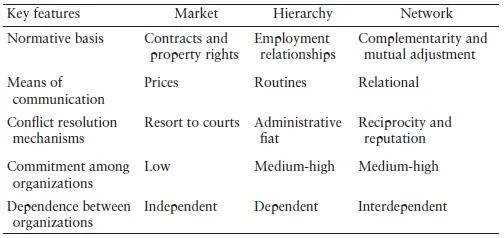

The first stage of the market is competitive interaction between actors (in gen- eral terms, buyers and sellers) who bargain over opportunities and exchange of resources. In the second stage, actors agree about the bargaining and exchange the agreed resources (Ebers, 1997b). The market mode relies on contracts and property rights to function, and its principal means of commu- nication is price. The resolution mechanism of conflicts between organiza- tions in this mode is legal action, and the commitment between parties tends to be low. Organizations are assumed to be totally independent of each other (Powell, 1990). When a nonprofit delivering aid to homeless people buys its produce for its kitchen from a wholesale food retailer, outsources its financial management to an accounting firm, and contracts out its transport services, it is coordinating with all these other organizations via the market mode.

In contrast, interorganizational relationships in hierarchical modes are based on employment relations, and the main means of communication is routine. Ultimate conflict resolution is done via administrative fiat (orders given by those in authority), and commitment between parties tends to be medium or high. With hierarchical modes, organizations are clearly depen- dent on each other (Powell, 1990), in superior-subordinate relationships. An example of the hierarchical coordination mode is the relationship between the headquarters of an international development nonprofit with its subsidiary organization in a developing country. The headquarters approves the strategy and determines the basic operating rules of its subordinate local office.

The third interorganizational mode, the network, is often thought of as flat, which implies that relationships are based on loyalty and cooperation (Fran- ces, Levacic, Mitchell, & Thompson, 1991). Network modes use reciprocity and reputation as their main conflict resolution mechanisms (Powell, 1990). The means of communication between organizations is negotiation, and com- mitment is medium-high. The network mode implies complementarity and mutual adjustment between interdependent organizations (Powell, 1990). Table 1.1 summarizes the characteristics of the three governance modes.

Table 1.1 Summarized Comparison between Diff erent Interorganizational Governance Modes 2

These definitions of the different interorganizational modes are ideal- typical. In fact, different modes simultaneously govern the relationships between a given set of organizations (Lowndes & Skelcher, 1998). For example, these organizations may relate to each other primarily through a network mode, such as mutual adjustment, with high interdependencies, relational interaction as the main means of communication, and with all actors being highly committed. However, these organizations’ interrela- tionships may also feature characteristics of other governance modes (mar- ket, hierarchy), such as incorporating contracts into the relationships, or delegating authority to one of the parties.

Summing up the literature and common practices, networks are com- posed of organizations with independent decision-making; their decision- making is based on negotiation; and the interaction between members is repetitive, continual, and stable (Ebers, 1997b; Grandori & Soda, 1995; Kickert, Klijn, & Koppenjan, 1997; Powell, 1990). A specific type of inter- organizational network is the goal-directed network.

Although all interorganizational goal-directed networks have some com- monly shared, basic attributes, there still are major differences between dif- ferent types (Agranoff, 2007; Grandori & Soda, 1995).

Different Types of Interorganizational Goal-Directed Networks

Functionally, goal-directed networks may be distinguished as follows: Exchange, concerted action, and joint production networks—or limited, moderate, and broad cooperation networks. At one end of the spectrum, networks merely exchange information (informational networks). At the other, action networks are interagency adjustments that formally adopt

collaborative courses of action. In between are developmental networks, which deal with information exchange and education and member service; and outreach networks, which exchange information, sequence program- ming, exchange resource opportunities, and pool client contacts.

Hence, several nonprofits may set up an informational network to come together periodically and share their information on the latest events in the immigration policy field and on their projects. Additionally, these nonprofits may also teach each other skills and techniques in which some may be better than others (i.e. they have set up a developmen- tal network). One nonprofit may teach the others advocacy techniques, another may share its knowledge on mobilizing supporters through Face- book and Twitter, while another coaches the rest on grant writing. Yet, the members may go a step further and set up an outreach network, a forum where the different nonprofits lay out their advocacy plans to coordinate their actions and thus be most effective. Lastly, and most inte- grative, nonprofits may decide to actually execute j...