![]()

1Introduction

1 January 2005 was meant to be one of the most momentous dates since the creation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947 – perhaps more so than even the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995. It was on this date that the Multi Fibre Arrangement (MFA), the protectionist trade regime governing textiles and clothing (T&C) that had become a byword for the hypocrisy and double standards beneath the advocacy by rich countries of the virtues of free trade, officially came to an end. The liberalization of T&C had been agreed to as part of the 1993 Uruguay Round, whereafter the MFA was dismantled in four progressive but unequal stages culminating in the removal of the most sensitive quotas on 31 December 2004. But the story did not end there. In fact within a few months of the abolition of the MFA both the USA and the European Union (EU) had introduced new trade restrictions against Chinese imports. Although these measures were justified on the grounds of offering a ‘temporary’ transition period so as to allow producers affected adversely by liberalization further time to adjust to freer trade – precisely the same rationale used to justify the original MFA – what this effectively meant, for China at least, was that the MFA was being extended for a further three years. More to the point, these new trade restrictions appeared to contravene the basic principles of the new multilateral order. In other words, although the Uruguay Round formally brought an ‘end to a special and discriminatory regime that has lasted for more than 40 years’ and created the WTO wherein T&C would be ‘governed by the general rules and disciplines embodied in the multilateral trading system’ (Panitchpakdi 2004), the sector still appeared to be something of a law unto itself. It is this uniqueness that this book seeks to trace and to explain.

The textiles and clothing sector

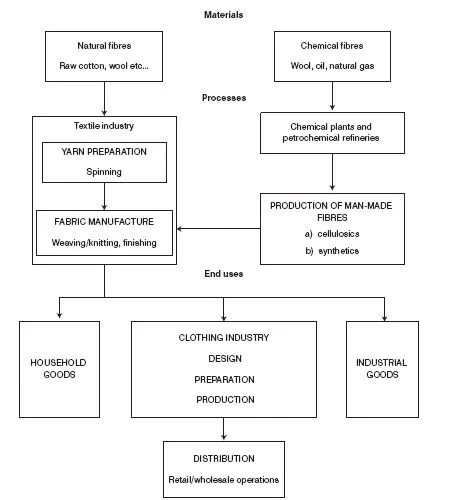

In many ways, T&C can be regarded as the quintessential ‘global’ industry, constituting the most geographically dispersed forms of manufacturing across both developed and developing countries (Dicken 2003; Dickerson 1999). The industry is made up of a number of distinct economic activities, each with its own specific technological and structural characteristics, ranging from the supply of raw materials and intermediate inputs at one end of the supply chain to the transformation of these inputs into end-use products and their eventual distribution and retail at the other end (see Figure 1.1).

Although the ‘upstream’ segment of the T&C chain is now generally characterized by high levels of technological innovation and capital intensification, in the ‘downstream’ clothing segment of the chain – the main focus of the book – the impact of technological innovation, especially in sewing and assembly stages of production that account for approximately 90 per cent of labour costs, has been minimal. As a consequence, the clothing industry’s association with low-cost barriers to entry and labour-intensive employment remains synonymous with ‘sweatshop’ employment practices, global outsourcing and trade conflict between rich and poor countries.

Theoretical speaking, T&C has arguably been at the forefront of two of the most important debates in International Political Economy (IPE) in the last 30 years. The first of these centred on the ‘new international division of labour’ first proclaimed by Folker Fröbel et al. in 1980. While this idea predated the globalization debate by a number of years, it nonetheless offered a precursor to precisely the sorts of concerns that would come to dominate IPE from the late 1980s onwards. In The New International Division of Labour (NIDL), Fröbel and his colleagues identified a qualitative shift in the nature of the political economy of North-South relations, away from an ‘old’ international division of labour wherein developing countries were restricted mainly to the export of raw materials, and towards a situation based on the dispersal and reorganization of manufacturing activity away from the core and towards the periphery. As they saw it, this new international division of labour was due primarily to the internal logic of capitalism itself as corporate managers sought to maximize profits in conditions of heightened global competition. To buttress these claims, Fröbel et al. used the case of outsourcing in the German clothing industry, which they claimed was driven by the attempts of transnational corporations (TNCs) to seek out the lowest possible labour costs and that this was leading to a re-allocation of elements of the production process towards those geographical areas where the cheapest and most compliant labour could be found. But Fröbel et al. went on to emphasize that this new international division of labour was not due to the conscious strategies of individual firms; nor for that matter was it a response to the policies pursued by particular developing countries. Rather:

Figure 1.1 The textiles and clothing production chain

Source: adapted from Dicken 2008: 318

The new international division of labour is an ‘institutional’ innovation of capital itself, necessitated by changed conditions, and not the result of changed development strategies by individual countries or options freely decided upon by so-called multinational companies.

(Fröbel et al. 1980: 46)

Of course, in the 30 years since the original publication of The New International Division of Labour this type of structuralist logic, and the neo-Marxist methodology underpinning it, has fallen out of fashion while the NIDL thesis as a whole was in time subject to numerous powerful critiques (Jenkins 1984; Gordon 1988; Mittelman 1997; Dicken 2003). Even so, the more substantive claim of the NIDL thesis – that is, that the international division of labour was driven by the ‘cheap labour’ strategies of TNCs – arguably left a more enduring mark on the debate. This is almost certainly true in the clothing industry. Although the geographical dispersal of clothing manufacturing documented originally by Frobel et al. was, and is still, claimed to be indicative of the broader pattern of structural change within the international political economy, the industry is actually characterized by a number of technological and structural features which render it far more supportive of the NIDL thesis than other forms of manufacturing. Despite all of this, the extent to which the international, or global, division of labour can be understood as an expression of the ‘cheap labour’ strategies of Western TNCs is still questionable, even in the case of T&C. Indeed, as we intend to argue, although structural and technological characteristics render the sector more supportive of the NIDL thesis than other comparable forms of manufacturing, a more important determinant of the geographical dispersal of T&C was the complex system of protectionist quotas which operated under the MFA between 1974 and 2004. Even though the MFA was supposedly intended to create an ‘orderly’ transition through the gradual opening-up of Western markets to exports from developing countries, in practice the subsequent renewals of the regime (1977, 1982, 1986, 1991) served to place increasingly restrictive quotas on most of the leading exporters. Paradoxically, however, these policies exacerbated the problems faced by developed countries by actually heightening the economic capabilities of developing country firms, as well as intensifying the scope of foreign competition as progressively more non-regulated countries entered the market (Gereffi 1999). In sum, the globalization of the T&C industry has been, at least to some degree, an unintended consequence of the protectionist policies pursued by Western governments.

The second debate in which T&C has figured prominently is that centred on hegemonic stability thesis (HST) which of course dominated mainstream IPE scholarship in the 1980s and 1990s. As is well known, HST correlates the smooth operation of the liberal economic order with the provision of global public goods, underwritten by a leader, or hegemon, willing to impose them and accept a disproportionate share of the cost of their provision. In the absence of such leadership in or in a situation in which the hegemon loses the capacity to impose these regimes, HST predicts a corresponding decline in their strength and durability, and hence a weakening in the liberal economic order. In Liberal Protectionism, Vinod Aggarwal drew on these insights to argue that the gradual ‘weakening’ of the post-war T&C regime – by which he meant the proliferation of protectionist quotas in contravention of the spirit of the original agreement and wider norms underpinning the multilateral trade order – was a direct consequence of US hegemonic decline. As originally conceived, Aggarwal argued, the MFA was consistent with the US preference for what he referred to as ‘liberal protectionism’. During the course of the 1970s, however, as US dominance of the international trading system began to dissipate, the MFA gradually came to reflect the preferences of the European Economic Community (EEC) for a more protectionist regime. As a result, the progressive hardening of the MFA from the late 1970s onwards was consistent with the theory of hegemonic stability, insofar as the latter predicted ‘strong regimes when a single power is dominant’ (Aggarwal 1985: 4).

Although Aggarwal’s interpretation of the MFA was consistent with and supportive of HST, he claimed at the time that his account furthered the debate in two important ways. On the one hand, Aggarwal qualified his reference to hegemonic stability by insisting that the theory only provided an accurate explanation of regime strength if it was operationalized in terms of issue-specific capabilities. In the case of T&C, Aggarwal claimed that, because these products tend to be more demand-elastic than other goods, market dominance needed to be measured specifically in terms of market power, rather than simply by reference to wider sources of geoeconomic or geopolitical power. On this reading, he suggested, the USA was overwhelmingly the dominant player in the international T&C trade during the 1950s and 1960s, but by the late 1970s it had been overtaken by the EEC. Thus, it was the change in the distribution of capabilities measured specifically in terms of T&C consumption that accounted for the hardening of the MFA from the late 1970s onwards. On the other hand, although Aggarwal’s thesis was in the spirit of neorealist thinking of the time in the sense that it favoured ‘systemic’ over ‘reductionist’ explanations, he was at pains to point out that his account did not neglect domestic factors. Indeed, Aggarwal specifically argued in a separate paper that, in relation to the 1981 MFA renewal, domestic interest groups in both Europe and the United States proved to be a ‘significant constraint’ on the type of regime that was ultimately agreed upon (Aggarwal 1983: 643). But in the final analysis Aggarwal saw the evolution of the T&C regime as closely corresponding to the theory and predictions of the hegemonic stability model, as his ultimate conclusion regarding the 1981 MFA renewal testified:

Changes in the strength and nature of the regime appear to be caused by a shift in the distribution of capabilities and increasing competition from newly industrializing countries in the textile and apparel subsystems. In the matter of regime strength, the absence of a hegemon to impose or cajole others into subscribing to an international regime led to an accord that was of necessity a product of compromise between two key actors – the EEC and the United States.

(Aggarwal 1983: 643)

As in the case of the NIDL thesis, the benefits of hindsight enable us to reject both Aggarwal’s specific thesis regarding the T&C trade regime as well as the broader theoretical assumptions on which it rests (see Milner 1998). There is of course the obvious empirical point that US hegemonic decline – if indeed that is what occurred – did not lead to the further ‘weakening’ of international regimes, nor to spiralling levels of trade protectionism. In fact, in the light of the successful conclusion of the Uruguay Round in 1993, it might be argued that the precise opposite was true. At the same time, given the emphasis that hegemonic stability theory placed on systemic sources of regime change, it has difficultly accounting for the marked variation of regime dynamics across different sectors. To put the point another way, if the trajectory of international regimes could simply be ‘read off’ from changing structures of global economic power, then how would we account for the idiosyncrasies that have historically and continue to characterize the regulation of different industries, not least T&C?

The argument of the book

This book is concerned with the politics and political economy of trade protectionism and liberalization in T&C; more specifically, it seeks to trace and to explain why the sector has historically proven to be, and arguably remains, such an anomalous case with respect to the multilateral trading system. The two literatures already briefly mentioned offer us some important clues as to where we might begin our investigation. The NIDL thesis, for its part, alerts us to the changing structural context beginning in the early 1970s associated with the intensification of capitalist competition and the geographical dispersal of manufacturing – and given the low entry barriers and labour-intensive patterns of accumulation closely associated with T&C one can see the escalation of protectionist pressures in high-income countries as a logical corollary of this process. However, this still fails to explain why trade protectionism became much more prevalent in T&C than in other industries, even those with similar technological and economic characteristics that were also the subject of global outsourcing, e.g. footwear, toys and consumer electronics. Meanwhile, Aggarwal’s HST-inspired account does point to the importance of global leadership and changes in the distribution of economic power in shaping regime dynamics. But this still does not account for the decision in the first place to create a separate regime for T&C – a decision, moreover, presumably taken when US global hegemony was in the ascendency.

In other words, the decisive shift in the regulation of T&C occurred not in the 1970s when ‘liberal protectionism’ supposedly gave way to ‘illiberal protectionism’, but at a much early date when the original decision was taken to effectively exclude T&C from the post-war multilateral trading system and to establish a parallel system of trade governance – a system, it hardly needs to be added, which was both highly discriminatory and non-reciprocal. The approach we take in this book is that this parallel system of trade governance is understood best as a by-product of policy institutionalization and path dependency. While acknowledging the due influence of systemic pressures, alongside important technological changes, we draw upon historical intuitionalist insights in order to show that the MFA – and the economic consequences that this had for both developed and developing countries – was a result of the particular way in which sectoral trade preferences were mediated through political institutions. Once translated into policy, these trade preferences became embedded within a particular set of regimes that developed and changed over time, the result of which ultimately shaped the distributional politics of both protectionism and liberalization. In other words, the global political economy of trade protectionism and liberalization in the T&C sector needs to be understood as a path dependent process that was heavily influenced by the embeddedness of policy regimes and attendant patterns of political and economic behaviour.

This argument is underpinned by a conceptual framework that obviously takes its cue from historical institutionalism. In the field of IPE, historical institutionalism has in the past been deployed to good effect to reveal the political structures and patterns of behaviour that exist within policy making bodies and negotiating arenas. This is especially so in case of the GATT/WTO. According to these accounts, institutions are said to promote asymmetries in negotiating power that persist over time, thus locking in patterns of negotiation and policy making that are procedurally unfair; moreover, the trade flows that result from such unfair policy processes are said to perpetuate (and even exacerbate) existing global economic inequalities, which are then carried by states and their delegates into future trade rounds, adding another layer of historical legacy to negotiation (Steinberg 2002; Smith 2004; Narlikar 2005; Wilkinson 2006). In this book, we draw inspiration from these accounts but deploy historical institutionalism in a slightly different way by considering the institutional legacies beholden by policy itself rather than the forum(s) within which policy is made. We will argue that by taking a different level of analysis – namely, the sectoral level – we can consider how the economic activity and political coalitions that accumulate around pre-established policy regimes – what we might refer to as the day-to-day governance of a sector – shape heavily the types of reform possible in international negotiations. In other words, patterns of trade protectionism and liberalization (or otherwise) of international trade exhibits a path dependency but not one that is captured entirely by those historical institutionalist accounts that focus principally on international organizations as the arena of political action.

Theoretically speaking, then, the book explores the form and effects of path dependency in international trade and, in so doing, what it adds to the literature is the application of a methodological technique that can illuminate the ‘inner logic’ perceived in sectoral trade reform and the (often overlooked) differences in liberalizing policy measures that result. In other words, the book addresses not primarily the underlying reasons for change, but rather sectoral constraints placed on change as manifest in the legal, political and ideational commitments of agents. To these ends, the next task is to set out, albeit very briefly (for a more lengthy account see Heron and Richardson 2008) what path dependency entails, the benefits and dangers it carries, and how it can be set into a framework through which to study the institutionalization of trade policy. According to Adrian Kay (2005), path dependency is neither a framework nor a theory in itself but an organizing concept, a me...