![]()

Chapter 1

Employment relations in an era of global markets

A conceptual framework chapter

Anil Verma, Thomas A. Kochan and Russell D. Lansbury

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the new terms of international competition and technological innovation have radically altered markets and the organization of production in many industries around the world. Markets have become simultaneously globalized and segmented, and new technologies have provided opportunities for individual firms and even entire industries to experiment with alternative business strategies and structures. Together, these developments test or transcend the boundaries of traditional industrial relations and human resource practices, which are collectively referred to as employment relations1 throughout this book.

Much of what is required today of firms to compete successfully in international markets – the development of new products or the introduction of new process technologies, the reconfiguration of subcontracting relations or rationalization of internal managerial hierarchies, or simply enhancing the efficiency and quality of workplace operations and relationships – depends upon corresponding shifts in industrial relations and human resource practices. For example, many firms employing new technologies have relied on broadly skilled workers capable of performing a variety of jobs to operate these machines. This, in turn, has blurred the functional and hierarchical distinctions between different kinds of jobs or between labour and management more generally. Similarly, efforts to enhance product performance have led firms to transcend traditional boundaries between engineering, manufacturing and marketing, and establish cross-functional development teams. Once again, these new organizational arrangements have required new skills and greater attention to human resource issues.

Both of these examples illustrate a more general trend towards the increasingly strategic role of employment relations within the firm. The new competitive strategies being promoted by firms today build on a variety of industrial relations arrangements and human resource practices which enhance the skill base and flexibility of the workforce and promote greater communication, trust and coordination among the firm’s various stakeholders. Yet this process of reappraisal and the renewed centrality of human resources are neither universal nor uniform. Although a new approach to employment relations appears to be emerging in most, if not all, industrialized nations the particular forms it has taken, and the extent to which it has been diffused, vary considerably both within nations and across industries and regions, as well as across countries with radically different institutional arrangements and historical traditions.

To set the context for the chapters to follow, the first section of this chapter reviews the theoretical background which has informed this research project. The second outlines the evidence from the experience of OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries. The third section addresses issues of special relevance to IR/HRM (industrial relations/human resource management) in newly industrializing economies (NIEs). The final section outlines the research framework which has been used by the authors of the individual country chapters.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Much of the prevailing research and theory in comparative industrial relations rests on the work organized around the Ford Foundation inter-university study on industrial relations practices, published under the auspices of the Wertheim collection at Harvard. This work was heavily influenced by John T. Dunlop’s Industrial Relations Systems (1958), which advanced the notion of industrial relations as a distinct sphere of socio-economic activity, producing rules of the workplace and understandable in terms of national systems. The perspective which emerged in these studies was synthesized by Kerr, Dunlop, Harbison and Myers in Industrialism and Industrial Man (1960). It placed a heavy emphasis upon functionalism or the ability to understand and explain practices by their contribution to economic efficiency and social stability. It embodied a considerable degree of technological determinism, a view that the evolution of industrial relations was being driven by a singular technological dynamic over time. It also reinforced American ethnocentrism, in the sense that the United States was seen as the technological leader and its institutions and practices as the model for efficiency. Patterns in other countries were generally viewed as being derivative of, or deviations from, the United States model. This tendency was reinforced by the fact that many prominent European industrial relations scholars at that time had studied in the United States. The major competing schools of industrial relations research were heavily influenced by Marxian scholarship (cf. Hyman 1975), which had a much more acute sense of class and ideological conflict, often offered a less functional view of the system and a different idea of the system’s historical trajectory, but was even less inclined to recognize and highlight distinctly different national patterns.

Both events and scholarship have undermined the perspectives generated by previous approaches. Particularly influential in this regard was the wave of labour protest and unrest which erupted in western Europe in the late 1960s, the growing recognition among European scholars that it could not be adequately captured within the framework developed by their American colleagues, and the emergence of distinct European strands of non-marxist industrial relations scholarship. More recently, the emergence of Japan, with its distinct labour and employment practices, has further challenged the pre-eminence of the American model and ideas about efficiency, as well as the historical evolution of national practices with which it was associated. Finally, the changes in practice in the 1980s and 1990s have called into question that model even with the United States itself (see Kochan et al. 1986).

Much of the new research, however, has been focused upon individual countries, often in the context of particular national debates (see Bamber and Lansbury 1993). It has thus produced a heightened awareness of national peculiarities, without generating a framework through which different national practices could be compared and evaluated. Several genuine international comparisons have, however, focused on pairs of countries. Of these, the most influential and important are Ronald Dore’s (1973) comparison of Britain and Japan, and the comparison of France and Germany by researchers based at LEST (Laboratoire d’Economie et de Sociologie du Travail) in Aix-en-Provence (Maurice, Sellier and Silvestre 1986). Together, these studies suggest differences among countries which are both more profound and more enduring than is consistent with the spirit, if not the letter, of the work of Kerr, Dunlop, Harbison and Myers. More importantly, the framework of US industrial relations theory is obviously inadequate for capturing the differences. In a sense, these studies represent very different approaches. Dore followed the earlier tradition in seeking to establish the relative efficiency of the two systems and predict, on that basis, the historical evolution of practice in other countries. The novelty of his argument was that Japan, not Great Britain and by extension not the US, became the best-practice model.

The LEST group, by contrast, presented two completely different but equally effective approaches to industrial relations and traced them to factors rooted so deeply within national culture and history that change seemed to be virtually precluded. Both Dore and the LEST team made efforts to extend their work to other countries, but with no clear results. Dore (1981, 1983) studied a group of developing countries, looking for but failing to find a tendency for late developers to follow the Japanese pattern in determinate fashion. The LEST approach has been extended by various researchers to Japan, Great Britain and Italy in a way which seems to reinforce the lesson that national patterns are peculiar. However, their later work did not really address the question, which seems critical to practical problems posed by the competition among countries and enterprises, about what can be learned from other experiences. Recent comparative studies of Australia and Sweden have reinforced the usefulness of comparisons between matched countries (see Lansbury, Sandkull and Hammarström 1992).

One lesson which the LEST studies made clear, and which is also implicit in Dore’s work, is that industrial relations by itself is not a self-contained domain of activity. It needs to be understood in terms of related activities as well as broader social and cultural structures. These include, at the very least, the system of education and training and of labour market regulation. In the United States, industrial relations policy also generates a quantitatively significant portion of what in other countries is provided by the social security system and hence must be understood in combination with social security.

Growing dissatisfaction with traditional frameworks and interpretations has stimulated researchers to re-examine developments within their individual national settings in order to find a better explanation and understanding of the changes under way (see for example: Accornero 1992; Adler and Cole 1993; Edwards and Sisson 1990; Shirai 1983; Streeck 1991; Chaykowski and Verma 1992; Piore and Sabel 1984; Kern and Schumann 1984; Kochan, Katz and McKersie 1986; Lansbury and Macdonald 1992; Osterman 1988; Mathews 1989; Regini 1991). Yet to date, little effort has been made to look across countries to update perspectives on comparative industrial relations and human resource policy questions. For an exception to this statement see the latest work of the Industrial Democracy in Europe Research Group (1981, 1993). This book represents an effort to look at the experiences across a set of newly industrializing societies in order to update and, in the process, reconceptualize our understanding of employment relations. It also draws upon evidence of changes which have occurred within advanced industrial countries in recent years (see Kochan et al. 1995). It is hoped the book will help rekindle comparative analysis of employment practices, broadly defined, to include both traditional fields of industrial relations and human resource management.

Understanding the adaptation process

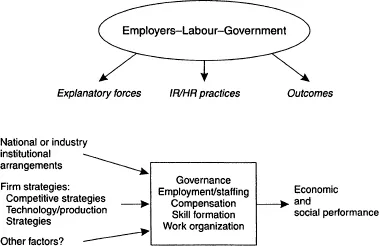

The purpose of this book is to develop a better theoretical and empirical understanding of the factors that influence the patterns of adaptation we observe in employment relations in response to these common pressures. To do so we have tried to employ a common analytic framework, displayed in Figure 1.1, to study developments within each country. At the heart of Figure 1.1 lies the set of human resource practices that we have chosen as windows through which to examine changes in employment practices. These are: first, the nature of work organization; second, skill formation; third, compensation systems including both their structure and levels; fourth, employment security and staffing; and finally, corporate governance. Further details concerning these IR/HR practices are included in the Appendix. We see these as being shaped by a combination of the external pressures of adaptation, the competitive strategies and technologies individual firms choose to employ in adjusting to increased international and domestic competition, the role of government and other national and/or industry-level institutions, and the changing role of the key factors to the employment relationships. Given our industrial relations heritage, we are especially interested in understanding how human resource strategies, practices and professional efforts relate to the overall governance of the firm, to industry-level structures and institutions and to the macro economic and political institution of the country. In turn, we see the patterns of employment relations and these broader institutional arrangements in industrial relations as having a direct and significant effect on how well the employment system performs on the key goals or outcomes of interest to the parties.

There is an emerging debate between two ways of interpreting the changes we are observing in practices across different countries. The first interpretation sees change as being driven and the outcomes of these changes as influenced primarily by the strategies that firms, unions and government policy makers adopt in response to changes in markets and technologies. This school of thought sees the enterprise as an increasingly important level of activity and analysis in industrial relations. The second view is that while enterprise-level strategies and actions are important, they can best be understood as being structured and influenced by the national and/or industry-level institutional arrangements and patterns that exist among the key actors – government, business and labour – in society. In reality, we are learning that both of these sets of forces, and, therefore, both of these perspectives, are important in shaping patterns of transformation and adaptation in employment practices in different countries. Changes in markets and technologies can and are being mediated in their impacts on individual firms and workers through national institutions and policies.

Figure 1.1 Initial framework for organizing the comparative IR/HRM research project

Source: MIT (1991). We appreciate the inputs of H. Druke and Russell Lansbury to this framework.

Note: Within any single country IR/HR practices vary across industries, firms and over time and all the variables in the model may be shaped by different combinations, employer, labour, and government influence.

Yet even where national institutions have historically been powerful, in advanced industrial economies such as Sweden, Norway, Australia and, to some extent, Germany, the range of micro-level variation in response appears to be increasing. We believe that this micro variation can best be explained by examining the range of choices and strategic responses that the parties take within different countries. Indeed, we believe these choices are critical determinants of the extent to which individual firms can gain competitive advantage through their human resources and affect the conditions of employment of their firms and, in the long run, the standards of living in their society. Thus, we need to keep both the role of national institutions and local variations and strategic choices of the parties at the micro level in mind as we move our work forward.

EVIDENCE FROM OECD COUNTRIES

From recent studies of changing employment relations in various OECD countries,2 several general patterns and conclusions are emerging (Kochan, Locke and Piore 1995). This chapter summarizes them briefly with the caveat that what follows is just an initial review of the evidence we have available to date.

Most OECD countries are experiencing intensified pressures to adapt their traditional practices in response to increased global competition and changing technologies. Thus, a general transformation process seems to be under way around the world that has some common features. Yet, there is considerable variation in the pace of change and the degree to which different industrial relations systems have been able to adapt through minor incremental adjustments as opposed to fundamental transformations in their systems.

One common aspect of the adaptation process is stronger emphasis on enterprise industrial relations activities. But more than just a decentralization of the structures of industrial relations is occurring. A search for greater flexibility in how work is organized and labour is deployed and an increase in the communications between management and the workforce seem to be the critical aspects of this drive to decentralize. Those systems that were already generally decentralized and that have institutional arrangements that promote flexibility and communications, such as Japan and perhaps Germany and Italy, seem to have been able to accommodate the need for this form of decentralization through incremental adaptations of their existing systems. By contrast, countries that have traditions of tight job control or Tayloristic forms of job regulation, such as the Anglo-Saxon countries – the UK, Australia, Canada and the US – and were more highly centralized in structure, such as Sweden, have experienced more fundamental changes or transformations in their industrial relations systems. This finding reinforces for us an appreciation that history matters a great deal. One cannot understand either the pace or the nature of changes occurring in a given country or setting without first understanding the historical context in which these common pressures are occurring.

A second...