![]()

Part I

Reflections on complex and contested concepts

![]()

1 Linking the discourse on sustainability and governance

Pamela M. Barnes and Thomas C. Hoerber

Sustainability and sustainable development

The concepts of sustainability and sustainable development are not the same. Originating in debates about the potential of the ecosystem to subsist over time, sustainability may be defined as the long-term goal to reach the destination of a more sustainable world. Sustainable development may be defined as the processes and pathways to achieve sustainability. However, both are contested concepts and subject to a number of interpretations. Crucially, however, ‘discussion and debate about the concepts of sustainability and sustainable development provide a focus for contact between contending positions (Myerson and Rydin 1996) and so become essential parts of the practice and process of working towards sustainability’ (Disendorf in Dunphy et al. 2000: 21).

During the 1987 UN World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) the participants ‘came to see that a new development path was required, one that sustained human progress not just in a few places for a few years, but for the entire planet for the future’ (WCED: 8). The model of sustainable development which was the result of the WCED deliberations was ‘development which meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (WCED: 43). Sustainable development, by viewing the three pillars of economic growth, ecological protection and social equity as interlinked and interdependent, significantly altered the political discourse about how economic and environmental objectives should be embedded into governance structures.

In the 2000s, the linkage of sustainable development and governance emerged as a focus for research in the literature of the discourse on sustainability (Lafferty 2004; Baker 2010). It is to this aspect of research that the cases in this volume make a contribution. But, as a first step it is crucial that shared ideas and common referents be established in the political discourse on sustainable development, as ‘public policy is not only expressed in words, [but] it is literally “constructed” through the languages in which it is described’ (Fischer 2003: 41).

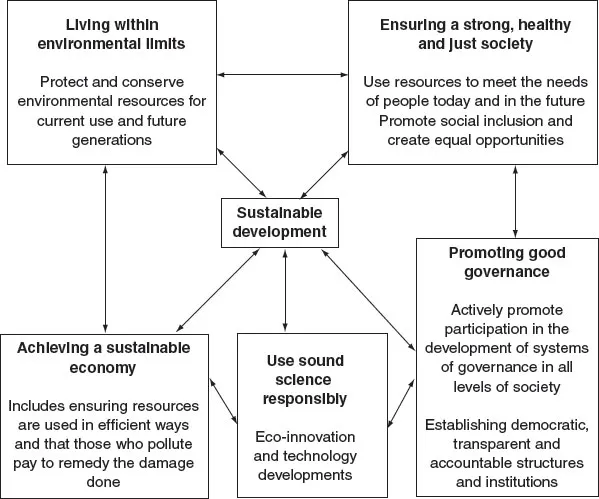

Figure 1.1 Principles of sustainable development strategy in Europe (source: adapted from SDC 2011: 7).

Unpacking the contested concepts of sustainable development and governance in Europe

During the 1960s and 1970s concerns intensified about the degradation of the environment as a result of economic growth in the industrialized world, including what was then the European Economic Community (EEC). The high profile (and very pessimistic in tone) ‘Club of Rome’ report published in 1972 was extremely influential (Meadows et al. 1972). The report was criticized, however, as it concentrated solely on the physical limits to growth and portrayed the future as one in which environmental ‘Armageddon’ would be the outcome of the then chosen path of economic development. The discourse which was current during this period was one of seemingly irreconcilable differences between those whose focus was the environment and others whose focus was economic growth and development. The environmental discourse was seen as incompatible and separate from that of the development discourse. The development discourse consisted of economic growth and modernization theories, but without addressing critical environmental and ecological issues. Both the environmental and the development discourses appeared to ignore questions of inter-generational dependency and under-development caused by environmental challenges: ‘In short the major theories and models of development articulated under the conservative-capitalist and radical-socialist perspectives (had) a common drawback in their relative indifference towards the implications of environmental issues for human development’ (Haque 2000: 4).

As the 1980s progressed, it was evident that such disparate views were unacceptable to politicians and the general public and did not lead to constructive action. The search was on for a more positive and comprehensive model of development which would form the basis of political and economic policies and instruments. The United Nations World Commission on Development (1984) produced what has become the accepted and authoritative conceptual model of sustainable development in its 1987 report (commonly known as the Brundtland Report (BR), named after its Chair, the then Norwegian Prime Minister, Gro Harlem Brundtland). The BR model of sustainable development replaced the Western centric model of development which emphasized economic growth. The model sought to reconcile the ecological, social and economic dimensions of development both at the present time and into the future:

Humanity has the ability to make development sustainable to ensure that it meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs … [furthermore] sustainable development is a process of change in which the exploitation of resources, the direction of investments, the orientation of technological development and institutional changes are made consistent with future as well as present needs.

(UN WCED 1987)

The Brundtland Report started from the viewpoint that

ecology and economy are becoming ever more interwoven locally, regionally, nationally and globally into a seamless net of causes and effects … [and that as] … poverty is a major cause of global environmental problems it is futile to attempt to deal with environmental problems without a broader perspective that encompasses the factors underlying world poverty and international inequality.

(UNWCED 1987: 20–21)

The objective of the report was to establish the connection between the economy and the environment as the basis upon which to build a just and equal society, a model which is ‘an aspiration that almost everyone thinks is desirable: indeed it is difficult not to agree with the idea’ (Baker 2006: 5).

The concept of sustainable development, as presented in the Brundtland Report, was considered to be vague on detail and without any significant policy proposals, but this vagueness has proved to be a strength as it has enabled crucial political debate to take place. The lack of specific policy proposals in the BR has provided the framework for a flexible dialogue to be established and opportunities for the conceptual model to evolve as environmental and economic conditions change. This is not to deny the complexity of the issues which are encompassed within the conceptual model or the difficulties of embedding the principles of sustainable development into the political discourse, nor is it to deny the problem of devising structures and instruments of governance which will deliver the policies needed to achieve a sustainable future. It is evident that since the 1980s this concept has become a significant aspect of political discourse at all levels of governance. It has acquired the status of a hegemonized discourse, as described by Laclau and Mouffe. This dominant position has been established because the Brundtland view provides the possibility of a new era of economic growth, in contrast to the view presented by those who supported the view outlined in the 1972 Club of Rome report and other similar reports and analyses.

In order to achieve sustainable development strategies, clear political leadership with co-ordination and coherence in policy is required. Institutional and administrative infrastructures which enable the co-ordination of all those involved in the policy process are an important complement to the policy measures. Short-term solutions, which are often favoured by national politicians, do not provide the long-term commitments needed for sustainable development strategies. Furthermore, ‘the real world of interlocked economic and ecological systems will not change, the policies and institutions concerned must’ (UN WCED 1987: 25). As the strategies necessary for sustainable development have been developed within governments, it has become accepted that sustainable development should be considered as ‘a journey, not a destination (but) with the key requirement that we should all be moving in the right direction’ (SDC 2011: 7).

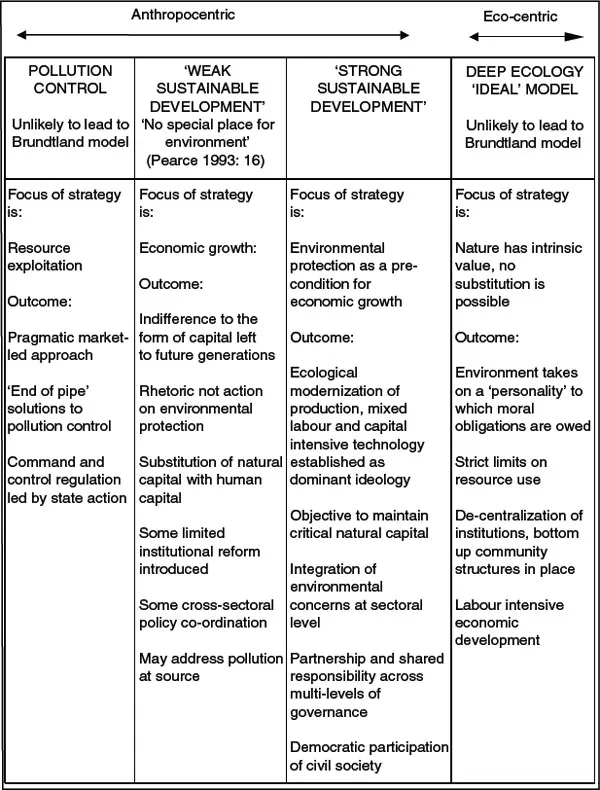

The European Union policy on sustainable development provides the overall political and policy framework within the geographic region of Europe for a number of reasons. As the EU has enlarged, the number of European states subject to EU policy on sustainable development has grown to 28 member states (Croatia having acceded to the EU in 2013). Greater economic integration within the EU and between the EU and other European states has increased the impact of that policy. The enlarged EU has gained an enhanced role and reputation in international conventions and negotiations relating to sustainability and sustainable development. The EU’s Sustainable Development Strategy thus provides an appropriate framework from which to analyse the changing nature of the discourse in the developed world. However, it would appear that Europe is not yet on the path towards genuinely sustainable development. Two issues are identified in this book which explain this failure on the part of the EU. The first relates to the extent to which the concept of sustainable development at EU level is consistent with the development of the concept itself. In Figure 1.2 a typology of development is presented in which the Environmental Action Programmes (EAP) of the European Union are used to indicate the extent to which the measures advocated in the EAPs are consistent with the Brundtland model of sustainable development. The second is the seeming lack of effectiveness on the part of the EU to develop a sustainability discourse which may then be embedded into the governance structures at the supranational level.

Figure 1.2 Evolution of the discourse on sustainability in Europe (adapted from Pearce 1993: 18 ‘The Sustainability Spectrum’, and BAKER 2006: 30 ‘The ladder of sustainable development: the global focus’).

Note

The view of proponents of weak sustainable development is that there is no place for the environment, but if it is assumed that all forms of capital are substitutable fewer roads may be offset for the future by more wetlands, or if natural resources are depleted (e.g. fossil fuels) this may be accompanied by investment in substitute fuels – i.e. investment in renewable energy (Pearce 1993). The outcome would be one in which the environment was protected, but it would not be the focus of the strategy.

The Brundtland model has informed the Sustainable Development Strategy of the European Union. Since the mid-1990s sustainable development has become ‘an overarching objective of the European Union, set out in the Treaty, governing all the Union’s policies and activities’ (Council of the European Union 2006: 2). The legal basis for action on sustainable development has been strengthened since the introduction of the commitment to ‘sustainable growth respecting the environment’ in the Treaty on European Union in Maastricht (adopted 1993). Sustainable development is now a fundamental objective of the European Union and is included in the Treaty on the European Union (as amended by the Lisbon Treaty, December 2009). The commitment of the Union is to ‘work for the sustainable development of Europe based on balanced economic growth and price stability, a highly competitive social market economy, aiming at full employment and social progress, and a high level of protection and improvement’ (Article 3.3 TEU). Furthermore, the Union is to work together to ‘foster the sustainable economic, social and environmental development of developing countries, with the primary aim of eradicating poverty’ (Article 21.2 TEU).

Underlying the European Union’s commitment to sustainable development is the view that it requires a long-term and ambitious strategy, if the goals of improved quality of life and wellbeing are to be achieved, for present and future generations. Linking economic development, protection of the environment and social justice is the key objective. It is evident that the Brundtland model is based on a long-term process of change dependent upon ‘10% regulation and 90% commitment’ which must come from all members of society (Baachelot-Narquin 2004: 42). The EU’s discourse also recognizes that sustainable development strategies are required in order to respond to the cross-cutting nature of the concept, encompassing many different sectoral public policy areas. At the supranational level the EU has governance structures and mechanisms in place to enable a longer-term perspective for sustainable development policies to be adopted and monitored. But despite the fact that differing dimensions of sustainable development have been included in environmental and economic debates and discourse since the 1980s, the linkage of economic sustainability and ecological sustainability is not fully recognized in the policy making of the European Union (EU). The discourse continues to be historically and context-specific, contingent, incoherent, partial, and evolving slowly.

It is possible to trace identify these aspects of the sustainability discourse in the EU through the initiatives of the EU’s Environmental Action Programmes (EAP), the first of which was adopted in 1972 [First Environmental Action Programme (1972–1977), followed by others 1977–1982, 1982–1987, 1987–1992, 1992–2002, and 2002–2012]. The approach of the first EAP was to advocate the development of command and control initiatives designed to resolve specific pollution control problems, such as acid rain. This reflected the discourse of the period and demonstrated an approach which was unlikely to lead to an effective and comprehensive sustainable development strategy. However, it was evident by the time the EU adopted the Fifth EAP (1992–2000) that the approach had become closer to the ‘strong sustainability’ position, as shown in Figure 1.2. The changing nature of the commitment to a strategy for sustainable development was shown in the use, for the first time, of a specific title for the Action Programme ‘Towards Sustainability’. The initiatives proposed in the Fifth EAP concentrated on measures targeting specific sectoral policies and priorities in order to achieve the sustainable development objectives. The discourse had shifted from its origins as action on pollution control to a model based on ecological modernization as the dominant ideology (see also Chapters 2, 13 and Conclusions of this volume for further discussion). It thus appeared that the current EU Sustainable Development Strategy (SDS) and Treaty commitment to sustainable development were consistent with sustainable development as outlined in the Brundtland model. More recently, in the 2010s the EU Strategy on Sustainable Development appears, arguably, to be positioned within the broad spectrum of strong sustainability, as shown in Figure 1.2.

Deepening in the process of European integration appears to have followed from the increased commitment to sustainability made amongst the EU states. When the earliest of the EAPs were adopted, the EU was engaged in Treaty revision, which led the European Economic Community to become the European Union. The first of these Treaty changes – the Single European Act (SEA) of 1987 – was a significant break-point in the development of the supranational competences of the EU with regard to sustainable development objectives. Although sustainable development was not included in the SEA, the principle was introduced that environmental objectives should be taken into account in the EU’s sectoral policies, a process known as ‘environmental protection integration’ (EPI). EPI is a key element in the introduction of sustainable development as it ‘is intended to be an important first order principle to guide the transition to sustainability’ (Lenschow 2002, cited in Jordan and Lenschow 2010: 147). The inclusion of the principle of EPI in the EU’s Treaty provided the legal and constitutional framework to enable ecological protection to become integrated into the economic policy priorities of the EU.

Despite this orientation, the 1987 Treaty change was driven by ec...