1

FDI Flows, their Determinants, and Economic Impacts in East Asia

Shujiro Urata

The author thanks the participants of the “Foreign Direct Investment and Economic Development: Lessons from East Asian Experience” project for their helpful comments. He is particularly indebted to Chia Siow Yue for detailed and helpful suggestions on an earlier version of this chapter.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has contributed to the economic growth of the recipient (or host) economies in important and varied ways. Not only has FDI brought financial resources for fixed investment. It also has brought new technology and managerial know-how to the recipient economies, thus further promoting economic growth. In addition, FDI has enabled the recipient economies to utilize sales, procurement, and information networks developed by foreign firms. This has greatly improved efficiency in production and marketing.

Several studies confirmed the positive contribution of FDI to economic growth. Borensztein, de Gregorio, and Lee (1998) examined the economic growth of sixty-nine developing countries from 1970 to 1989. Their regression analysis showed that FDI had a marginally positive impact on economic growth, but it had a significantly positive impact when the FDI was undertaken in the countries with high educational attainment. Their findings suggest that education plays an important role in the effective use of FDI. United Nations (1999) examined the economic growth of more than sixty countries from 1971 to 1995 and obtained results similar to those of Borensztein, de Gregorio, and Lee (1998). Kawai and Urata (2003) found that FDI had significantly positive impacts on economic growth by analyzing the data for 133 countries from 1970 to 1997. Among the countries in various groups, East Asian countries experienced particularly strong positive effects on economic growth from FDI.

Various factors help explain East Asian economies’ rapid economic growth in recent decades. Among them are high savings and investments, export expansion, and the availability of educated and hard-working labor. In addition, FDI has made an important contribution to remarkable economic growth in East Asia since the mid-1980s. Indeed, the formation of the FDI-trade nexus has played a crucial role in achieving high economic growth (Urata 2001). Although FDI inflows to many East Asian economies declined as a result of the outbreak of the crisis in the late 1990s, some economies (such as the Republic of Korea and Thailand) saw an increase in FDI inflows, and this aided in their economic recovery. Even in East Asian economies that experienced a decline in FDI inflows, the magnitude of the decline was much smaller than the decline in other types of financial flows, such as bank lending and portfolio investments. Based on this observation, one could argue that FDI lessened the negative effects of the crisis in many East Asian economies.

Aware of the important connection between FDI inflows and economic growth, many East Asian governments are keenly interested in attracting foreign direct investment. This chapter examines the recent patterns of FDI flows in East Asian economies and attempts to identify the factors that have influenced these flows. Such analysis may prove useful for other economies seeking to attract FDI. In addition, the notable impact of FDI on trade and production systems in East Asia is examined.

The chapter begins with a discussion of FDI inflows and outflows in East Asia. The policy environment affecting foreign direct investment is then examined at the global, regional, and bilateral levels. Topics addressed include the following: trade-related investment measures (TRIMs) in the World Trade Organization (WTO); Non-Binding Investment Principles affirmed by Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) members; bilateral investment treaties and free trade agreements; and FDI regimes in East Asia. Next the chapter evaluates the extent of FDI liberalization by East Asian economies and the determinants of FDI inflows. The effects of FDI on intraregional trade and emerging regional production systems in East Asia are also explored. The chapter concludes with a review of the findings.

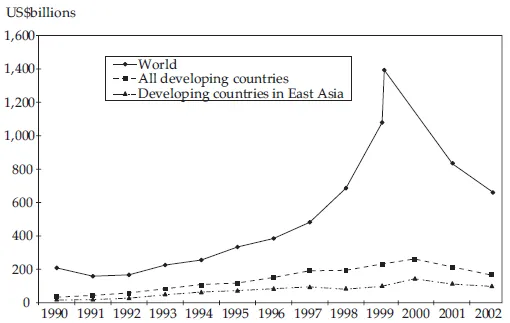

FDI Inflows and Outflows of East Asian Developing Economies

FDI inflows worldwide increased substantially in the 1990s before beginning to decline in 2001 (Figure 1.1). This rapid increase is attributable to several factors. Technological progress and deregulation in communication services reduced the cost of international communication, helping multinational corporations (MNCs) to conduct international business through FDI. Liberalization in FDI policies by many countries also contributed to the expansion of FDI. The decline in the annual flow of world FDI in 2001 was largely attributable to a slowdown in economic growth in the United States and in members of the European Union. The main cause of this slowdown was the bursting of the information technology bubble and the terrorists’ attacks in the States.

Similar to the pattern observed for world FDI, FDI inflows in East Asian developing economies experienced an increase in the 1990s and a decline in the early 2000s. The rate of change, however, was significantly smaller than that experienced by the economies in other regions. Specifically, annual FDI inflows to East Asian developing economies increased sharply from approximately $20 to $30 billion in the early 1990s to $136 billion in 2000. From this peak they declined to $93 billion in 2001 and to $84 billion in 2002 (Appendix Table A1.1). According to United Nations (2003), major causes of the decline include weak economic growth, low corporate profits, and the winding down of privatization.

Figure 1.1. FDI Inflows to the World, Developing Countries, and Developing Countries in East Asia, 1990–2002

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Foreign Direct Investment database on line.

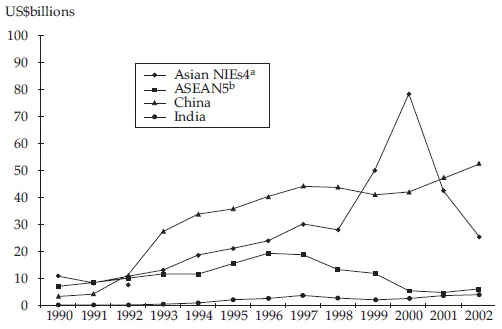

FDI inflows in East Asian developing economies varied widely (Figure 1.2). China experienced a steady increase in its FDI inflows from the early 1990s to 2002. Unlike China, ASEAN5 saw a steady increase in FDI inflows until the outbreak of the currency and financial crisis in 1997; FDI in those five countries dramatically declined in the following years.1 China surpassed ASEAN5 in the early 1990s and has widened the gap notably since then. In 2001 FDI inflows to China were more than ten times larger than for ASEAN5. The newly industrializing economies (NIEs4)—Hong Kong, China; the Republic of Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, China—experienced a steady increase in FDI inflows from the early 1990s to 1998 and a dramatic increase in 1999 and 2000. In the following two years, however, NIEs4 saw a precipitous decline in FDI.

Figure 1.2. FDI Inflows to Developing Countries in Asia, 1990–2002

a. The Asian newly industrializing economies are Hong Kong, China; Taiwan, China; Republic of Korea; and Singapore.

b. Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam are the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) 5.

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Foreign Direct Investment database on line.

As noted earlier, among East Asian developing economies, China has attracted FDI successfully since the early 1990s. Indeed, China has been the largest recipient of FDI among developing economies since the early 1990s, and it became the world’s largest recipient of FDI in 2002. Some of the factors that make China an attractive host country for foreign direct investment include its large market and low-wage workers, trade and FDI liberalization, and accession to the World Trade Organization.

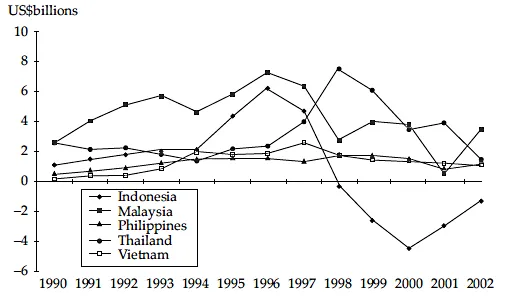

Among ASEAN5 countries, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia recorded notable increases in FDI inflows before the 1997 crisis (Figure 1.3). Thereafter, FDI inflows to Malaysia and Indonesia dropped significantly. In Indonesia they turned negative in 1998, and this disinvestment continued through 2002. Political instability appears to be an important factor behind the decline in FDI in Indonesia.2 In Thailand, unlike Indonesia, FDI inflows increased after the crisis and remained at relatively high levels through 2001. The Thai government promoted FDI inflows by liberalizing FDI policies. From 1990 to 2002 FDI inflows to the Philippines and Vietnam remained relatively constant.

Figure 1.3. FDI Inflows to ASEAN5, 1990–2002

Note: ASEAN refers to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Foreign Direct Investment database on line.

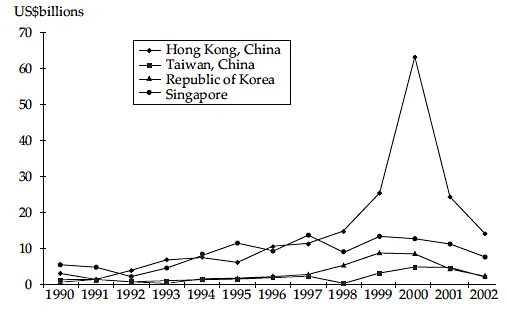

Among the Asian NIEs4, Hong Kong exhibited substantial growth in FDI inflows in 2000 (Figure 1.4). Although they declined sharply in 2001, the level of FDI inflows to Hong Kong was still substantially larger than the levels achieved by other NIEs. It is important to note, however, that FDI inflows to Hong Kong may be overestimated. This is because a substantial portion of them were reinvested in China. A large increase in 2000 was due to a single large investment in the telecommunication sector worth $23 billion (United Nations 2001, 25). Singapore, which kept pace with Hong Kong until the outbreak of the financial crisis, experienced a decline in FDI inflows after 1997, although it regained its attractiveness quickly. Korea recorded a substantial increase in FDI inflows in 1998 that can be largely attributable to the Korean government’s drastic liberalization of FDI policies to deal with the negative impacts of the crisis. Similar to the pattern observed for Korea, FDI inflows in Taiwan increased after the crisis, although the magnitude of the increase was much smaller.

Figure 1.4. FDI Inflows to Asian NIEs4, 1990–2002

Note: NIEs refers to newly industrializing economies.

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Foreign Direct Investment database on line.

FDI inflows to India remained small until the mid-1990s when they began to grow (Figure 1.2).3 The pace of the increase accelerated in the 2000s, largely reflecting liberalization of FDI policies.

A substantial part of FDI inflows in East Asia appears to have taken the form of reinvestment financed by earnings from the overseas affiliates of multinational corporations. According to the International Monetary Fund (2002), the shares of reinvested earnings in FDI inflows for China, Hong Kong, and the Philippines in recent years were approximately 30 to 50 percent. High shares of reinvested earnings reflect multinational corporations’ favorable performance in these countries and mature investments that yield profits for reinvestment. In addition, FDI policies of the recipient countries that restricted or discouraged the repatriation of profits resulted in high shares of reinvested earnings.

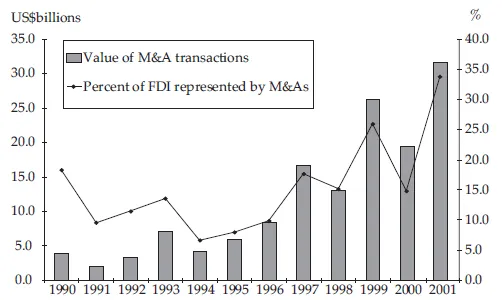

One notable development concerning FDI in East Asia in recent years is the rapid expansion in crossborder mergers and acquisitions (M&As), a development observed in developed economies as well. M&A transactions in East Asia increased sharply after the crisis in 1997, their value growing from $8.4 billion in 1996, to $16.7 billion in 1997, to $31.7 billion in 2001 (Figure 1.5).4 Among developing economies in East Asia, the crisis countries (Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand) recorded substantial increases in M&A transactions. The percent of FDI inflows for East Asian economies represented by mergers and acquisitions increased from 10 percent in 1996, to 18 percent in 1997, to 34 percent in 2001.

At least two factors contributed to the expansion of M&A transactions. First, a sharp decline in the value of equity in terms of foreign currency (currency depreciation) increased the attractiveness of M&A purchases for foreign investors. Second, liberalization of restrictions on M&A transactions facilitated crossborder mergers and acquisitions. The host economies’ capability to assimilate technology and management know-how, in order to reap benefits from FDI inflows, became more important. Because mergers and acquisitions do not expand physical capacity, an improvement in technological capability through successful technology transfer is a major source of benefits. After the 1997 crisis, mergers and acquisitions played a crucial role in the survival of firms by injecting capital and introducing a new management style.

Figure 1.5. Mergers and Acquisitions in East Asia, 1990–2001

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Foreign Direct Investment database on line.

As FDI inflows to East Asian developing economies expanded, MNCs became more important (Table 1.1). This table shows two types of information for selected East Asian economies: the importance of MNCs in employment, sales, and value added, and the ratio of FDI inflows to domestic capital formation. The importance of multinational corporations to the East Asian economies varies widely. MNCs have a sizable presence in Singapore, Malaysia, and Hong Kong; in terms of employment and/or sales for the manufacturing sector in these economies, MNCs contribute as much as 40 to 80 percent. Although significant, the presence of MNCs in Taiwan, China, and Vietnam is smaller than in Singapore, Malaysia, and Hong Kong. Multinational corporations’ presence in Indonesia and India is very limited.

For many countries, the ratio of FDI inflows to domestic capital formation increased in the mid-1990s, reflecting the increase in these investments (Table 1.1).5 The economies with a high ratio—around 30 to 50 percent—include Singapore and Hong Kong. Those economies registering around 10 to 20 percent include China, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam. Very low ratios (less than 10 percent) are observed in Taiwan, Indonesia, Korea, and India.

FDI inflows and their importance in the economic activities of East Asian economies differ as a result of various factors, including current economic conditions, the FDI policy environment, and the country’s future economic outlook. Before examining the FDI policy environment in the next section of this chapter, we briefly consider the patterns of FDI outflows from East Asian economies and the United States, a major investor in East Asia.

Most foreign direct investment for the period 1990 to 2002 was provided by developed countries. Indeed, FDI outflows from developed countries represented 90 percent of the world total (Appendix Table A1.4). This dominance of developed countries in FDI outflows is particularly notable once one realizes that for FDI inflows developed countries had 73 percent of the world total for the 1990–2002 period; the corresponding value for developing countries was 27 percent. The high share of developed countries in FDI outflows when compared to FDI inflows can be explained by developed countries’ abundance in capital, technology, and management know-how, so necessary for making foreign direct investments. The United States saw large and growing FDI outflows in the 1990s, reaching $175 billion in 1999 before starting to decline in 2000. Unlike U.S. FDI outflows, Japanese FDI outflows stayed at a low level (around $25 billion) in the 1990s before starting to increase in 2000 and 2001. The sharp contrast between the United States and Japan in terms of FDI outflows largely reflects the two countries’ contrasting economic performance. The U.S. economy was performing extremely well, and therefore U.S. firms actively invested overseas. Japanese firms did not invest actively abroad because of their poor performance at home.

Among East Asian developing economies, Hong Kong has been a very large supplier of FDI flows (Appendix Table A1.4). As noted earlier, however, the data presented in the table include not only FDI from local Hong Kong firms but also FDI from foreign firms, because Hong Kong was an intermediary for foreign firms from other countries. In addition to Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, and Korea have been actively investing abroad. These findings indicate very interesting developments in East As...