Introduction

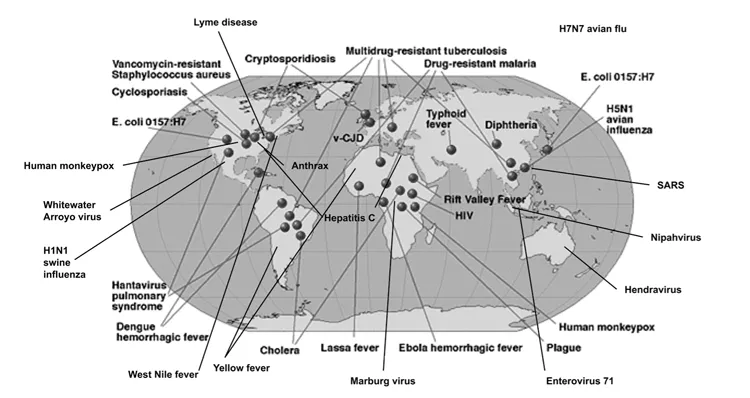

Despite remarkable advances in microbial research during the twentieth century, infectious diseases still remain among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. More than three dozen new high-impact infectious diseases have been identified since the 1970s. The list includes Legionnaires’ disease, SARS, HIV/AIDS, Lyme disease, hepatitis C, new forms of cholera, cryptosporidium, Ebola, toxic shock syndrome and E. coli 0157:H7, among many others. With this in mind, emerging infectious diseases may serve as a paradigm for handling the public threat of bioterrorism. Figure 1.1 shows the global distribution of some of these agents.

With this in mind, it is important to look at emerging pathogens in the context of global biosecurity. We need to understand why these pathogens are emerging, how they will impact us, and what we can do to intervene in that process. We need to understand how naturally occurring agents differ from intentionally introduced, man-made or genetically engineered ones in their spread and ability

to sustain their contagiousness. With vastly different infrastructures and resources, we also need to understand how differently – for better or worse – the third world would handle a pandemic.

The global devastation of pandemics of smallpox and plague in the Middle Ages as well as HIV/AIDS and influenza in more recent times has influenced every aspect of life, including life expectancy, economics, health-care delivery, employment, and freedom of movement. Plague in the Middle Ages introduced us to the term “quarantine” when ships, for fear of spreading plague, were unable to unload their cargo and crew for 40 days.

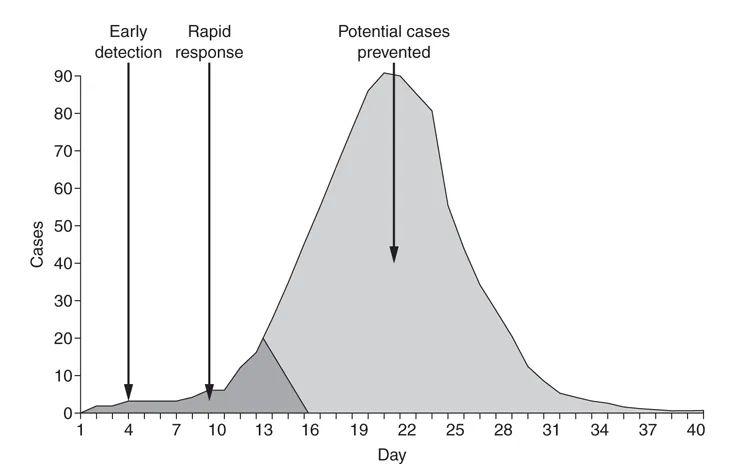

Destructive bioagents can linger (e.g., smallpox) or appear, disappear, and reappear without warning (e.g., plague or influenza). Will a biological threat agent like non-contagious anthrax cause more or less harm than contagious agents like pneumonic plague, smallpox, or a hemorrhagic fever virus? Understanding these diseases will help us better prepare for them, avoid them or, at a minimum, diminish their impact. Figure 1.2 shows how the epidemic curve of cases over time could be affected with an efficient response mechanism.

Recognition

Without the benefit of good record keeping, it is hard to judge the impact of emerging pathogens in the distant past. Some, like HIV/AIDS, may have previously occurred but affected only small numbers of people in isolated places. Without the benefit of current microbiologic techniques or mathematical modeling, some may have occurred throughout history but are only now recognized as

Table 1.1 Emerging infectious diseases

Table 1.2 Re-emerging and increasingly resistant diseases

distinct infectious diseases. Many infections, for example, look exactly like influenza.

We can categorize high-impact bioagents into three groups: emergence of new infectious diseases, re-emergence of previously recognized infectious diseases, and persistence of high-impact “old” infectious diseases. In this chapter we will concentrate on the first two categories.

Emerging diseases include outbreaks of previously unknown diseases (e.g., SARS, HIV/AIDS) or known diseases where a strain’s incidence or pathogenicity in humans has significantly increased in recent decades (e.g., S.aureus and tuberculosis). Re-emerging diseases are known diseases that have suddenly and dramatically reappeared after a significant decline in incidence (e.g., new strains of hantavirus, importation of monkeypox). A re-emerging agent may merely have changed its geographical preference (e.g., West Nile virus in the United States or mad cow disease in Britain), its pathogenicity (e.g., influenza), or its overall impact (e.g., tuberculosis, C.difficile, MRSA). Within recent decades, innovative research and improved diagnostic detection methods have revealed a number of previously unknown human pathogens. For example, many chronic peptic ulcers, which were formerly thought to be caused by stress, genetics, or diet, are now known to be the result of infection by the stomach bacterium Helicobacter pylori.1

Contributing factors

Some of the drivers of disease pandemics impacting their emergence or re-emergence are:

1 Changing human demographics and behavior. This includes drug use, excessive or inappropriate antimicrobial use, rapid concentrated population growth, urbanization, or movements of large numbers of refugees into camps with poor hygiene and sanitation.

2 Ecological factors. This includes agricultural and industrial changes, land use such as deforestation, desertification, and global warming.

3 Animal or insect contact, including close contact with, consumption of, or attack by diseased animals.

4 Random genetic mutation like influenza strains changing from year to year via genetic drift or genetic shift.

5 Malicious people who wish to harm others with biological weapons like sending the anthrax letters of 2001 or infecting salad bars with salmonella in 1984.

6 A globalized, shrinking world. Examples include airline travel and SARS, cholera from water on ships, widespread distribution of infected beef from feedlots, and Salmonella or hepatitis A from the import and export of food.

One innovative approach to study the causes of emergence was taken by a group of epidemiologists that looked at 335 infectious diseases since 1940. They found that 60 percent originated from animal contact (e.g., SARS, HIV) and 20 percent were from drug-resistant pathogens (e.g., S.aureus and enterococcus), and this occurred mostly in developed regions where antibiotic use was most prevalent.2

Changes in human demographics, behavior, and land use are contributing to new disease emergence by changing transmission dynamics to bring people into closer and more frequent physical contact with novel pathogens. Some diseases were well contained until a new environmental factor emerged. For example drought and Hantavirus in the Four Corners area of the United States brought humans in closer contact with rodents and their aerosolized urine. The breakdown in water sanitation in Milwaukee, Wisconsin brought us in closer contact with the parasite cryptosporidium, causing widespread diarrheal illness with over 400,000 cases.3 At other times, new diseases suddenly emerge from encroachment on exotic animals or foods, or with no confirmed precipitating factor.

Human behavior plays an important role in both emergence and re-emergence of diseases. Increased and sometimes imprudent use of antimicrobial drugs and pesticides has led to the development of resistant pathogens, allowing many diseases that were formerly more easily treatable with antimicrobials to make a comeback (e.g., tuberculosis, malaria, some nosocomial (hospital) and foodborne infections, resistant S.aureus). Decreased compliance with vaccination policies have led to the re-emergence of diseases such as measles, mumps, diphtheria, whooping cough, H.influenza type B, and pertussis, which were previously under excellent control with global eradication programs. Polio made a temporary resurgence in parts of Africa as a result of Nigerian Islamic clerics who told their congregants that polio vaccine was a Western attempt to sterilize Muslim women.4 It took several years and a concerted effort by the World Health Organization (WHO) to try to contain this man-made and unnecessary outbreak.

Emergence may involve exposure to animal or insect carriers of disease as well as to humans. The close proximity of many animals to each other and to humans, especially in food markets in Asia, as well as the increasing trade in exotic animals for pets and as food sources, has contributed to the rise in opportunity for pathogens to jump from animal reservoirs to other animals, including humans. For example, close contact with exotic animals like the Ghanaian rat was found to be the origin of the 2003 outbreak of monkeypox, which then spread to prairie dogs in United States.5

Natural genetic variations, recombinations, and adaptations allow new strains of known pathogens to appear to which the immune system has not been previously exposed, and is therefore not primed to recognize. For example, will a highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza strain mutate to become communicable between humans? It is already communicable in poultry and waterfowl. The Asian food markets, where humans, ducks, and pigs are in close proximity, are a prime setting for this possible change in communicability. All three of these species harbor influenza viruses, and the pig has the ability to harbor all three.

There were three influenza pandemics during the twentieth century, the first of which, the Spanish influenza of 1918–1919, may have been the most destructive pandemic of all time, causing tens or even hundreds of millions of deaths worldwide.6 Smaller pandemics occurred in 1957 and 1968. There is now concern that the highly pathogenic H5N1 virus, which currently has a high mortality but lacks contagiousness from person to person (to person), may mutate into a contagious form to cause a high-mortality pandemic.7

The new H1N1 (swine) influenza virus that first emerged in 2009 also caused great concern, having started small in the spring just like Spanish flu did almost 100 years previously. Initially there was a high rate of deaths reported from Mexico. From there the virus quickly spread to countries on almost every continent, but caused very few deaths. WHO was confronted with a relatively non-virulent virus in pandemic form confounding its 1–6 phase classification system that did not take virulence into account. Authorities also had to decide if they wanted to add or substitute a new H1N1 component into the vaccine formulation for the fall of that year.8 They ultimately decided to make a second seperate vaccine.

Population growth, urbanization, and crowding are becoming more important factors in the emergence of disease. Geography, for example, can play a major role. The midwestern United States has a high concentration of livestock, a prime setting for the propagation of foot-and-mouth disease. The northeastern United States has a high population density and tends to over-utilize antibiotics and hand sanitizers, setting the stage for resistant bugs like the MRSA strain of S.aureus, C. difficile, and enterococcus. The Amazon has a low population density but is under pressure from encroaching communities with very different immunities. As another example, Nigeria is home to a large and growing population density, with Lagos soon expected to become the most populated city in the worl...