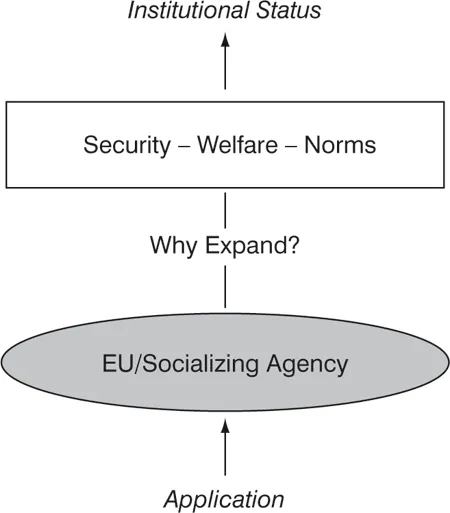

The following section provides the theoretical background of the analysis by combining the basic assumptions of rationalist and social-constructivist meta-theories with theories of institutions (Risse and Wiener 1999: 776–8). For this purpose, I introduce ontologically different ideal type actor models. Of course, I do not claim that, in reality, the EU does exclusively follow either the one logic or the other. But even if one assumes the EU to hold a multifaceted identity, one has to assess which part of its identity dominates its enlargement policies and under what conditions.

I start with introducing rationalist variables; the neo-realist ‘power’ approach and the neoliberalist ‘welfare’ variant, before moving to the social-constructivist variable ‘legitimacy’.

Rationalist institutionalism: enlargement – a matter of efficiency

Rationalist explanations of enlargement are based on an individualist ontology: the wholes are reducible to the interacting parts. Agencies (individual actors), not social structures, are central for action. Rationalism a priori presumes that all agents are self-interested and goal-oriented actors; i.e. the so-called homo oeconomicus or ‘calculating machine’, who is driven by instrumental rationality, pursues the maximization of it own material interest and follows a calculus logic of action, i.e. the logic of consequences (cf. Hopf 1998: 173): Each actor

Table 1.2 Enlargement: independent variables

egoistically calculates the costs and benefits of the available courses of action in advance. Within a means-end type of rationality, the courses are ranked in a fixed order of preferences. The option that maximizes the benefits and minimizes the costs is the one ranking highest; i.e. the optimal course to attain the fixed goal. The actors’ preferences, interests and identity are not assumed to change as long as the material conditions of the surrounding environment remain stable. As rationalist explanations are also based on a materialist ontology, the international system is considered a mere technical environment. Each actor’s individual preference can be exogenously determined by analysing the material structures, i.e. the share of the distribution of power and wealth given in his environment. Of all actors, rationalist theories regard the corporate unitary state as the key unit of analysis.

Moreover, rationalists are ‘thin’ institutionalists: the role of international institutions – be it norms or organizations – is believed to be limited, i.e. mere epiphenomena of the underlying material power structures. Thus, it is the given (material) interests that determine the preferences and behaviour of the agents and create institutions to attain their preferences more easily. International organizations are not assumed to take independent roles but function as the willing instruments of their member states. They are not considered to constitute the actors’ identity; any decision about membership or institutional status therefore depends solely on the egotistical (material) preferences of the organization’s member states rather than on the organization’s ‘management desk’.

Rationalism treats international organizations as ‘clubs’. The central rationalist approach to the issues of conditions of membership, optimal organizational size, and calculating the cost and benefits of enlargement, is ‘club theory’ (Bernauer 1995: 81, cf. Schimmelfennig 2003: 21). International organizations are instrumental associations designed to help states to pursue their interests more efficiently. They maximize their members’ utilities (power or welfare) by reducing the transaction costs of cooperation. If international organizations do not provide a benefit or net gain, i.e. extend governance and control to third states (power) or contribute to the state’s international profit-making (welfare), they are neither joined nor created in the first place. A club is a voluntary group of states sharing the costs of consuming a common good (Bernauer 1995: 91). If the good provided is a pure public good, which means that it is indivisible, non-excludable and non-rival, expanding membership is not costly and therefore unproblematic (Schimmelfennig 2003: 21). However, in most cases, international organizations provide impure goods, that is to say that any new member is an additional rival consumer, which reduces the present members’ benefit of sharing the good (Bernauer 1995: 89). As long as the costs of using the good less often are not fully matched by the new member’s contribution to the club (the membership fee), enlargement is unlikely because an expansion would render individual consumption more expensive for the current members (crowding effect). As every new member ‘disturbs’ the established and rather complex cost–benefit equilibrium, new members will only be admitted if their accession is of benefit. The institutional status hence depends on the extent to which a third state is beneficial to the organization and to each member state.

As all actors are considered strategic and self-interested utility maximizers, they aim at maximizing their benefits and minimizing their costs. The intra-organizational decision-making process will turn out as a two-level bargaining process (Putnam 1988). On the external side, the bargaining process between the organization (EU) and the third state is asymmetrical due to the fact that the third state faces the accumulated bargaining power of the organization’s member states. Another bargaining process will, however, occur internally, i.e. among the organization’s member states. Here, the more powerful member states will threaten the less powerful actors with their preferences (enlargement/ non-enlargement) or – in the event of equal voting rights – a group of member states will try to form a majority coalition to achieve their preferences. In the event of unanimous decision making – as is the case in the EU – enlargement cannot take place without each member st...