1 Half a century of development theories

An institutionalist survey

Robert Boyer

Introduction: the need to take a new look at a half-century of theories and strategies of development

Development economics offered a double specificity when it first emerged as a separate discipline at the end of the Second World War. For some analysts, it constituted an exception to the theories that were assumed to be operative in the developed economies. Others felt that the developing world could become a new zone of application for such theories – as long as they were adapted to its main characteristics. However, in both cases, development economics was only of secondary importance. As Axel Leijonhufvud humorously wrote in 1973:

The priestly caste (the Math-Econ), for example, is a higher “field” than either Micro or Macro, while the Develops just as definitely rank lower. . . . The low rank of the Develops is due to the fact that this caste, in recent times, has not strictly enforced the taboos against association with the Polscis, Sociogs and other tribes. Other Econ look upon this with considerable apprehension as endangering the moral fiber of the tribe and suspect the Develops even of relinquishing model-making.

(Cited in Bardhan 2000: 1)

This sort of tongue-in-cheek attitude fell out of fashion in the late 1990s, when development issues found themselves at the heart of some bitter controversies. Even more importantly, development studies have made a great deal of progress at the conceptual level, with many of its advances working their way into the very core of general economic theory. There are a number of examples. Theories of imperfect information and of “principal-agent” contracts (Stiglitz 1987) have nurtured thinking about the basic characteristics of a rural economy (Bardhan 1989b). Externalities relating to co-ordination problems have led to formalisations that deal as much with endogenous growth (Lucas 1993) as with the existence of multiple equilibria whenever preferences and strategies are interdependent (Hoff and Stiglitz 2001). As such, both the developed and the traditional economies’ characteristic problems can be dealt with as part of a unified framework.

However, in the end, a number of these strategies for development turned out to be failures, causing the world’s top theoreticians to raise questions as to why so many theories, based as they were on mechanisms that were simple and unique, had such limited capacities for explaining development. In the words of Irma Adelman:

Like chemists’ futile quest for the philosopher’s stone, over the past half-century the search for a single explanatory factor guided both theoretical and empirical research into development. As a discipline, economics seems incapable of recognising that this sort of factor does not exist, and that a policy of development requires an otherwise more complex understanding of systems, one that combines economic, social, cultural and political institutions, whose interactions themselves change over time. That as a result, interventions must be multiform. That what is good for one phase of development can turn out to be unfavourable at a later stage. That certain irreversibilities create path-dependency. In sum, that the prescriptions a given country receives at a certain moment in time should be rooted in an understanding of its situation, and of the trajectory that has led it to the present through a long period of history.

(2001b: 104–5)

A number of similar statements can be found in recent stances taken by top experts in development, as well as by other pacesetters in the field of economics (Emmerij 1997a; Sen 1997; Stiglitz 1998; Meier 2001; Revue d’économie du development 2001). This convergence raises two issues.

How and why did development theories converge, in the late 1990s, towards a systemic and institutionalist conception diametrically opposed to a “purely economic approach” that usually focuses on technologies, demography and markets? It would be illuminating to carry out an analysis, however brief this may be, of the stages that development economics passed through from the end of the Second World War until modern times. Development is a concept with a long history. The same can be said of those factors that are considered to be crucial in terms of the perpetuation of under-development – they too have changed greatly over the course of the past half-century.

At the same time, it would also be useful to revisit the period’s main governmental strategies, sometimes characterised by trust in a 100 per cent state system, and sometimes by the temptation to leave resource allocation – and even certain strategic choices – up to the market.

As regards the theories that are involved, the most notable studies into the potentiality of (and conditions underlying) a market economy have revealed a whole array of structural limitations that can undermine the efficiency of the market’s allocations (Ingrao and Israel 1990) or of its very functioning (White 1981) – not to mention the problem of its institutionalisation (Fligstein 1999). In short, a market is a social construction. In return, and quite symmetrically, public-choice theoreticians have concluded that it is not necessarily possible for the state to compensate for market failures, given that it suffers from the opportunistic behaviour of politicians (and of the senior civil servants in charge of implementing their decisions).

Therefore, if we are to answer the issue that lies at the heart of the present essay with any confidence, we will have to show that there are a multiplicity of reasons today why we should kick this habit of alternating between a belief in the state as an agent of development, and the belief that all we have to do is respond to the market’s signals. In other words, we do not in fact have to be slaves to the cyclical Kondratief-like thinking that seems to have marked the history of ideas, doctrines and economic theories on development-related matters. There may be another way of formulating this paradigm.

A half-century of trials and errors

The development concept’s long history

From the outset, economic policy-making was dealing with problems that today come under the heading of theories of development. The founding fathers often wondered (and argued) about the respective roles that the state and the market should be playing in this complex process. William Petty, François Quesnay and Adam Smith raised some significant questions. Does the market need the state; or to the contrary, will the market’s success deprive the state of its attributes? To encourage development, do we need more or less of a state? (Sen 1988: 10).

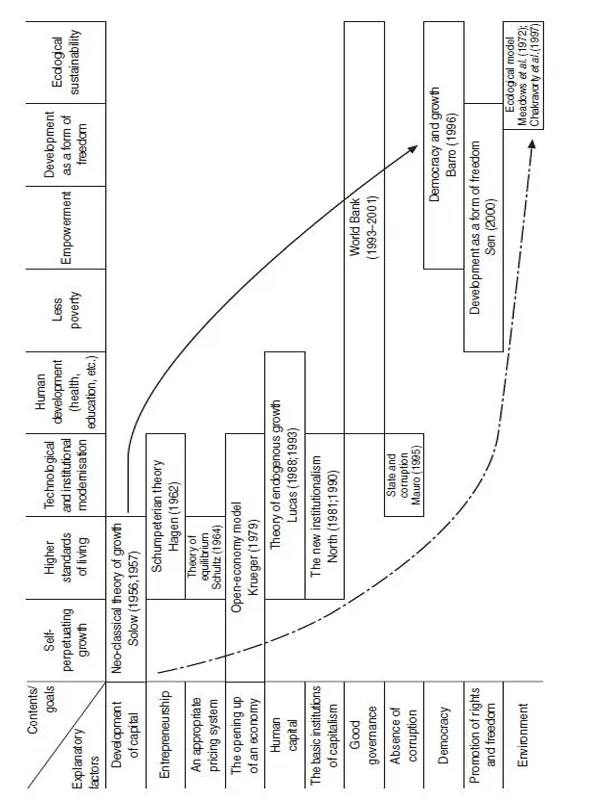

Development theory per se was only seen as a distinct discipline after the Second World War. Since then, the development concept has gone through an endless series of redefinitions and reinterpretations. To carry out a forward-looking analysis of development, it would be useful to take a quick look at the different definitions that have been attributed successively to the processes at work in those economies that were once described as “peripheral” (see Figure 1.1).

The first and most elementary definition stresses the self-perpetuating nature of growth, as opposed to simple phases of acceleration in a transient economic situation. This criterion relates to an important aspect in development, that is a country’s entering a phase of permanent growth as opposed to its tendency to stagnate, or to experience the sort of slow increases in output that were rife during the sixteenth century (Braudel 1979; Bairoch 1995).

Figure 1.1 A historical look at the substance and at the purpose of development.

Of course, growth could be a product of demographic changes rather than of rising standards of living. Hence a second definition stressing a quasi-continuous rise in per capita consumption as a criterion of development, considered here in the strictly economic sense of the term. It is this definition that theories of growth usually use, in line with a tradition that goes all the way back to Harrod or Domar models – although the canonical form is found in a neo-classical type of emblematic formalisation (Solow 1956, 1957).

Still, neither of these meanings accounts for a third essential component: the transformations of technologies, organisations and institutions that accompany the economic growth process per se. The development concept itself introduces the idea of a qualitative transformation and finds a significant reference in the Schumpeterian theory of development, as long as this application is not limited to entrepreneurs alone or to an entrepreneurial frame of mind.

This notion can be extended further by incorporating one of the main findings of historical demography, to wit, the spectacular human development that has taken place over the past two centuries. This has occurred at different levels: physical (growth in people’s average size); health-related (longer-life expectancies at birth); and intellectual (rise in collective and individual knowledge through training in reading and mathematics, and more generally by learning to think analytically and abstractly).

It is important to note that these variables define the objectives and contents of development, and not just one of its pre-conditions as has been assumed in recent studies of endogenous growth (Lucas 1988, 1993; Romer 1990). This received wisdom is the basis of the human-development indicators the World Bank uses. Published at regular intervals, these indicators lend themselves to a ranking that is somewhat different from classifications based on per-capita income (e.g. World Bank 1998). This demonstrates the multidimensional nature of development.

An analogous divergence crops up when national performances are measured by growth rates or by reductions in levels of poverty. Of course, economic dynamism provides the necessary resources for reducing distribution-related conflicts (Collier et al. 2001), but nothing guarantees that the least well off will receive their fair share of the fruits of growth. Much depends on the distribution of property – and on the institutions that shape the pricing and rewards systems (Adelman 2001a: 84). Hence a sixth definition of development as a reducer of poverty – the latter term being defined here as when people are deprived of a decent life.

Development analysis and theories of justice can be linked in an attempt to come up with a more general definition. According to Rawls (1971), development can be defined as the recognition that all individuals have basic rights, notably the right to operate in a framework that enables everyone to fulfil his/her potential as far as possible. This conception finds its extreme version in a definition that is radically opposed to a purely economic vision, and which assimilates development with freedom in the social, political and economic order (Sen 2000).

Lastly, increasing environmental problems have caused certain analysts to stress the ecological sustainability of a given mode of development. This is the criterion that is ultimately transplanted into the idea of the primacy of the economic regime’s social acceptability and political sustainability. This final definition has a distant origin in the Malthusian interpretation of development as a conflict between an economic dynamic and the exhaustion of nature resources. It has, however, taken on new forms, first when oil and raw materials prices skyrocketed during the 1970s (Meadows et al. 1972), and later during the 1990s, due to the fear of global warming (Godard et al. 2000).

All in all, over the past half-century, the development concept has been considerably transformed, to the point that it now encompasses a whole series of objectives relating to: the quality of the economic policy being followed; the investments being made in health and education as part of the reproduction of a society’s overall structure; political acceptance of a given economic order; without forgetting the economic activity’s place in the ecosystem. From its original ad hoc and limited relevancy in a domain that was purely economic (and even economistic) in nature, the concept’s definition has been extended to cover most of the orders that comprise a society, as well as the interrelationships between them. This has been achieved through the use of a systemic approach – even if this term has been rarely used (Adelman 2001a). An analogous trend has been observed with the different schemes for interpreting development, as well as systematic non-development.

From technology to modes of government: the progress made in the explanatory factors of development

Figure 1.1 highlights a remarkable parallelism between the changes in development-related ideas and the changes in the explanatory factors that theoreticians and analysts use.

At first, development economists drew their inspiration from the advances that had been achieved in the various theories of growth. Whether inspired by Keynes or by the reaffirmation of a balanced growth model, they saw the investment rate as the key factor over the long and medium term. In fact, cross-national econometric studies asserted that this was one of the most robust explanations for differences in growth rates over a period of one or several decades (Bradford de Long and Summers 1991).

The optimal growth theory shows that this type of relationship is not linear. Moreover, the experience of the Soviet economy confirms that it is important for social and economic institutions to define incentives to encourage the productive utilisation of the resources that have been allocated to investment and to innovation. Society’s ability to absorb technologies and innovations also cropped up as a key variable explaining differential rates of growth (Abramowitz 1986). Industrialising countries’ ambitious but unsuccessful development plans were sometimes attributed to a lack of talent in economic management, not to mention a shortage of entrepreneurs.

This raises a major issue, to wit, the main institutions of an economy that is being run according to market logic. On the one hand, economists tend to stress mechanisms such as price-based allocations, where non-development can only stem from the blocking of market mechanisms (Schultz 1964). On the other hand, the new institutionalism implies the need to transcend a logic that is based on property rights alone (North 1981) so as to...